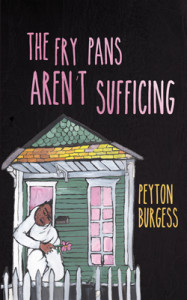

The Fry Pans Aren’t Sufficing (Lavender Ink, 2016), the first story collection by Peyton Burgess, proves that a story about disaster relief can be whimsical and a story about a woman giving birth to a koala can be darkly poignant. “Sometimes shocking and often strange,” Publishers Weekly calls the book “a fine debut from a striking new voice.” Burgess, a creative writing professor and Loyola alumnus (2004), admits being first drawn to fiction writing for the sheer enjoyment of making things up. A native of Virginia, Burgess grew up visiting grandparents in New Orleans, and easily transitioned to life in the Deep South when he moved to Louisiana to attend Loyola University. With heartfelt honesty and wry humor, Burgess dedicates the first part of the collection to stories that trace the shadow and emptiness left behind by Hurricane Katrina. In the second and third sections, he plays with genre, style and region. By way of this smart collection, the reader travels from Atlanta and Hattiesburg to the ghostly aftermath of the storm in New Orleans, from Manhattan to Chicago to Honolulu, and beyond. Along the way, more than a few of his characters demand the attention and respect of their audience—and leave an impression that’s not likely to fade.

INTERVIEWER

The first few stories are clearly inspired by the New Orleans and southern Louisiana landscape. Was this setting a natural choice? Is it easier or more difficult to write about your home?

PEYTON BURGESS

Yes, it definitely was a natural choice. The material was inspired by my experiences from wandering without a home after Katrina. This is easy because it’s familiar to me, but it’s hard because I care about these places and know I won’t be satisfied with my rendering. The stories take place in Atlanta, Hattiesburg, and then finally New Orleans. My hope was to make the loss feel a little less confined to New Orleans—that the loss and devastation would exist through the way the characters interpret the new circumstances in which they now find themselves and the dizzying feeling that sometimes comes with trying to orient yourself somewhere strange.

Abandonment and the loss of the house and home in New Orleans has been written about a lot. I wanted to write about trying to figure out an existence in a place that is welcoming you but also expecting you to vamoose soon, maybe very soon, depending on how much they can tolerate you.

Care has its limits, especially when somebody is introducing you as a refugee and not just by your name.

The story “Nauman’s Installation” is about this disorientation as well. I remember a bartender in New Haven calling me a Katrina refugee when she introduced me to one of her regulars. Then she comped my meal and bar tab. I was 23 and kept drinking and told myself I was on an adventure, but that bartender wasn’t going to just keep doling out drinks for free. The designation as refugee that came with that exciting and mournful adventure made me really uncomfortable. You can’t depend on generosity. Care has its limits, especially when somebody is introducing you as a refugee and not just by your name. So I think these characters feel very uncomfortable wherever they are until they go back home, even if there’s nothing much to go back to, at least they go back to just being themselves. And that’s why the first section of the stories ends in New Orleans.

INTERVIEWER

The characters in many of these stories end up connecting deeply with total strangers (a post office worker at a mail auction, for instance). But there’s also a palpable sense of loneliness in each of these stories. Are these characters experiencing early-to-midlife crises? Existential dread?

BURGESS

I think they’re just experiencing the crisis of losing a home, and that loss forces them to question everything or, perhaps out of desperation, to try and find some normalcy, like a familiar skillet or a memorable night dancing. By connecting to absolute strangers in these unfamiliar places, I think these characters hope to be understood as individuals, not just nameless victims of another overwhelming governmental and societal failure that most people don’t have the time or endurance to learn from.

INTERVIEWER

In the suite of stories set in the south, you’re able to capture the fight-or-flight survivor mentality that Hurricane Katrina left in its wake. Does writing about the storm become essential when a story is set in contemporary New Orleans? How did you navigate that while drafting and revising?

There have been other storms. There will be other storms. New Orleans has more beautiful and awful stuff to offer than just Katrina stories.

BURGESS

No, writing about Katrina is not essential at all when writing about New Orleans. There have been other storms. There will be other storms. New Orleans has more beautiful and awful stuff to offer than just Katrina stories. There’s no storm in the story “Sunday Bruch with Daisy,” just an idiot getting dumped and a dog getting killed. I will say, though, that my early drafts attempted to keep the settings nameless while being inspired by Hattiesburg and New Orleans as I experienced them during those times. The gesture was again not trying to isolate the experience to one particular storm or place, but the more I wrote and revised the more the cities demanded specific acknowledgements.

INTERVIEWER

Your stories riff on the omnipresence of banality. The title story includes a betting war for a decent skillet at a USPS mail auction; the much weightier aspects of the story arise almost as after thoughts: the narrator and his girlfriend are recent evacuees from Katrina, shacked up temporarily with the girlfriend’s family. Given the circumstances, the relationship experiences strain from lack of sex, communication, and so on. But yet, the action of the first story (and the two following) seems to revolve around the emotional or psychological significance in random objects. Perhaps the most poignant examples come in “On the Way End,” when a severely obese Good Samaritan, Antoine, offers to trade the couple (stranded after their car goes up in flames on the interstate) his truck for a sketch Baby Girl drew. What is the significance of these objects and the relationships they facilitate?

BURGESS

You’re right. The things that you might consider the weightier elements of a “Katrina story” are afterthoughts in these stories. I think when something like a house being destroyed or a car being flooded or mold growing all over everything are such common conditions like they were back then for so many, and those conditions are written about until the cows come home (in some cases miraculously produced and published months after whatever calamity struck in order to take advantage of said calamity’s buzz), then the real story becomes the smaller details about a character’s handling of that common condition later, over time, after the buzz is gone. We’re not with these characters so much for what happened to them and their stuff; that happened to everybody. We’re with them now in these stories to find out what they’re going to do with themselves and each other as they try to satisfy themselves with rebuilding, which sometimes involves getting new stuff and meeting new people and trying to figure out how to assign significance to the new stuff and new people, ultimately determining how they will contribute to a new life.

INTERVIEWER

The third section of the collection breaks stylistically from what precedes. One noticeable difference is that you move from longer-form stories to micro stories. The flash fiction proves refreshing, and almost gives the reader a chance to catch his or her breath before the emotional impact of the final story, “The Koala Conception.” How does use of the flash fiction form challenge you with regard to conflict and character? Can writing flash fiction inform or elevate prose more generally?

If anything, the collection is more about different approaches to writing.

BURGESS

The third section is newer material and really just an attempt to break away and find new approaches and content. In a way it’s also a return to the days when I first started writing because I just thought it was fun. I liked making things up and entertaining myself. If the reader gets to breathe, that’s because I was giving myself a chance to breathe and play around a bit. Flash fiction is something that I still need to figure out. I think it’s really good at challenging me to distill a feeling, but I get frustrated with it because usually the closer I get to a story the longer that story becomes. If anything, the collection is more about different approaches to writing. If I wanted to write a book that was tied together tightly through plot and characters, I would have written a novel.

Weirdly enough, “The Koala Conception” originally was an attempt at flash fiction: it started out as maybe 1,000 words of me just breathing and having fun, but then I kept discovering more story as I wrote (maybe in some cases non-story). There are a lot of tangents, probably a lot of stuff that your average editor and my writer friends would cut, but I had fun doing it. It’s one of the pieces in the collection that I’m proud of most, although it kind of worries me that in the case of that story I don’t care as much about what the reader thinks, because I typically consider the reader a lot. That’s a behavior that I’m still trying to measure.

INTERVIEWER

Your characters, their dialogue, and the predicaments they get themselves into are hilarious in a dark and wry way. It’s been said that humor and sex are two of the more difficult topics to confront in fiction, yet you capture the messiness and imperfection of both so well. What goes into your thought process when writing intimate scenes? How do you write playful prose without broaching cuteness or compromising narrative authority?

BURGESS

That sounds like a rather awesome compliment. Thanks! I’m worried I won’t be able to explain it or show that I don’t really know how it happens. There are a lot of things I don’t know, maybe that’s where humor comes from. We all know what happens when people have sex. Things go places, whatever. What interests me though is wrapping my head around the details related to why and how the sex did or didn’t happen according to how the characters probably imagined it would. And I think the playfulness probably comes from knowing that my reader is probably already familiar, fortunately or unfortunately, with whatever is happening, that I acknowledge it, and allow the reader to play along.

INTERVIEWER

Finally—and this seems like a cliché question, but I’m still interested in asking—what anxieties do you encounter when bringing your first book to press? What excitements?

I feel like there’s a drought of empathy out there, and I don’t think it’s a coincidence that people are not reading as much as they used to.

BURGESS

Oh, me! So many anxieties, some good and some bad. When I was finalizing the manuscript for submission to Lavender Ink, I suddenly became aware of several things that I felt needed to be addressed. Some stories changed a lot. I’m sure I could still be working on the book today, but I was also really ready to move on and excited to share it. There are days when I’m nervous about how it will be received, and I turn into a negative creep and tell myself that nobody really cares about this stuff anyway. But I think what makes me excited is the possibility of a shared experience with strangers, that somebody ends up caring about something or people that they don’t have to care about in order to get by day in, day out. I guess what I’m excited about is the possibility of somebody caring about a character that they don’t have to care about. I think exercising your abilities to care about people you don’t have to care about is really important. Maybe it’s not a matter of survival (although I could argue that it is), but at the very least exercising those muscles improves the quality of your life and the lives of those around you. I feel like there’s a drought of empathy out there, and I don’t think it’s a coincidence that people are not reading as much as they used to. But that’s been changing recently. Data I’ve read lately shows that the so-called “apathetic” 20-somethings are out-reading the very people that gave them that misnomer.

Erin Little graduated from Loyola with honors in English Writing in 2015. She is currently working in academic publishing in Manhattan.