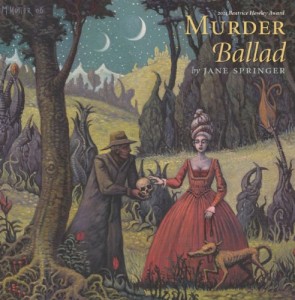

Murder Ballad, by Jane Springer. Alice James Books, 2012. $15.95, 80 pages.

Billie Holiday presides over Jane Springer’s Murder Ballad, winner of the Beatrice Hawley Award. It’s not the public radio cliché of the flower-wearing chanteuse that shadows the poems, but the one who sang “hunger” and “love” like nobody else and chased the “greasy pig of the self” through orphanages, addictions, and segregated America, lost her cabaret license, was shot up and slapped down and incarcerated and lived to become a witness to the blues she sang as ballads in nightclubs where G.I.s, for the smell of a woman, would pick her gardenia to pieces. That Billie Holiday. The Lady Day of “last resort” whose plush voice swallowed the circumstance of deprivation and the pang that provoked her, to give pleasure in song.

Springer hears “the cracked boards of Lady Day’s voice thrown into the musk-dirt yard” in the house that was the site of the dance of divorce and romance and ghosted hope, the ballad themes. The house, like the book, could be a “romantic, if irredeemable mess,” but Springer won’t let it get to mess nor clean it up by scrubbing out the “gravedirt.” It’s there to be sniffed or licked or overheard. It’s a big voice Springer has that retains its jagged idiosyncrasy, its jankiness. There’s a horizontal axis to it that sings of the past in Newellton, Louisiana, and god-knows-where Georgia that gets crossed with the vertical axis, the demonic and divine stuff, of a requiem. It is a voice big enough to sing of the umbilical, and “violent beauty,” and cobwebby, redolent swamp.

Murder Ballad has “the aura and authenticity of an archaeological find” as Seamus Heaney calls it. It’s ripe with all the textures of bayous, swamp cypress, underwater muck, and the “damp implosion of woodscent.” It starts in the frog-hunting, stump-pulling, front-yard chicken-tending South and ends in the retrospective distance of New York winters. You’d do well to have a mind of Alabama to fully comprehend the book, or let yourself be schooled in its secrets. And you’d do well to have the mind of a bloodhound to sniff your way through to a higher knowledge of this book, a knowledge that comes from the particles of honeysuckle and loam through the olfactory nerve to the frontal cortex without having to pass through the fancy transposing mechanism of the optical nerve and the bicameral brain. It’s primal and subtle (angelic and animal at once) and no accident that hounds (and beagles and wolves) figure so prominently in the book. “Looks Like the Hound Who Caught the Car” and “I’ll Wear the Hound out of That” are two titles in a book of titles that are themselves one-liners, ballads, smart talk, patois, adages, and Flannery O’Connor recoilings of stories that become immanent experiences, a “mighty pudder in the breast” (Hazlitt). “Let It Lay Where Jesus Flung It” and “Don’t Let Your Mouth Write a Check Your Butt Can’t Cash” are two titles that I especially love.

Murder Ballad thrives on a muchness, a long-lined plurality. It’s got a full ark of creatures great and small (chiggers, roped calves, she-goats, catfish, mules, mullet, indigo swallow tails, owls, anhingas, mastodons). The catalog of the bestiary doesn’t give a good sense of how pervasive the animal is both as consciousness and the DNA of subvocalized wonder. It’s an “anhinga of night,” for instance, “who dries his wings along the horizon” which takes the bird and makes it both a looming presence of the groom for the bride, a shape-shifting Ovidian presence, a pictogram of wish, doom, evening and a replica, perhaps, of the “anointed hour when sulking ends.”

I like the long poems that take the time they need for full body immersion. “Ether” is the actual name of the grandfather, “love’s anesthesia,” and the demon of scant sperm deposits, meanness and “dark consequence.” The poem’s namesake is also an absurdly (literal) dashing hero who drenches the second story fire and saves the father then an infant. The tangles of the long poems linguistic, narrative threads, traces of doses and scents and hard to swallow antidotes are here given “space to mourn love unrisen to earthly forms.” Springer is not shy about either the sentiment or the censure that these lines make. She survives the insults to the body and the psyche (see B. Holiday) and stitches “the broken seam between the ether & this dark earth.”

“Hindsight’s Ballad: I’d Go back and Fix Me, if I was My Own Daughter” has a similar humid, swirling complication set at the liminal territory of the ages of consciousness: from 11 to 16, from first kiss to prom, those American places of eroticism and danger and identity crisis. The blue smoke and “cardboard shakers of Creole hot stuff” could be shorthand for a southern experience that was haunted and outré. “Things multiply” in memory, in actual summer, and in the hot body of girl (whose purse holds a steak knife), but Springer clears a way to understanding by the eloquent singular “I see you” and “ I want to beg you” that make an aperture to the past through her older-self narrator and permits her to see the emerging self clearly and with the distinct intensity of “one.” These slightly liturgical moves in Springer’s work underlie the rituals of forgiveness and resurrection without overtly telegraphing the roundhouse punch.

She can work in an impacted, shorter form, as well, as in three brilliant ones: “Pretty Polly” (“Who made the banjo sad & wrong?”); the language drunk “Whiskey Pastoral” (“The gizmo that opens a window to Lethe”); and, the aborted love sonnet depicting the triangle of Hestersue, Jamal, and the narrator, “Pretty as you Please”—one big gulp of delicious, seething resentment.

Did I mention the names? Besides grandpa Ether, there is a genealogy, a hagiography of names that range from the generic offspring with tinctures of the South, Robertlee, Butch Merrit, the perfectly trochaic, Oscar Milby whose ballsack is tied to a brick (with a slipknot) and the lovely Candy Burnside and Voncille Platt (of the Platts of Tuscaloosa? you might ask). They form a constellation of influence and photographic recall like the names in Du Fu, historical, intimate, all honor to them and their incestuous progeny.

Because she’s a torch singer (even if the torch is a flashlight beam aimed at a coon up a tree as in “Face that Could Pull a Stump”) she has melopoetic chops. Here are two lines from “Ingénue”:

Because we sat cross-legged in a circle instead of warring over grief & oil or shoes

and everything else that made the blues, the blues

And here’s the start of “Hindsight Ballad”:

Now all is one highway. One combine, yellow, so long settled in the dirt – crows make

a disco of it. One logging truck, the Merritt’s, one cropduster whose circular sweep

of blue smoke is the summer’s news.

And here’s the deft dismount from “What We Call This Frog Hunting,” a “2 A.M. song” that stews together eros and thanatos so well that I’m not sure it’s about amphibious slaughter or first love:

This is the year: the dark, the boat, the sunken suits & watery forms,

the catch & kiss, damp canvas, split rib, dawn & entrails in the grass –

we cut the feet last – in the pleated heat –

then wipe our blades across our thighs & call this happiness

When done well, as it is here, the ballad form is about time (passing) and is a metonym of space that makes us realize a neither completely erased there or a completely distinct and self-sufficient here. The old imperatives of the ballad’s romance/death (and the longevity of the story) or Holiday’s hunger and love (and the timelessness of the cycle) are musiced in this book.

Murder Ballad lives between the “fossilized map” of the remembered territory and the lurking, flashing present. And although from the very first notes we have the sense it’s about something riven, it also has the quality of the wedding of the fecund place of becoming with the afterlife of “the poverty and riches of love.”