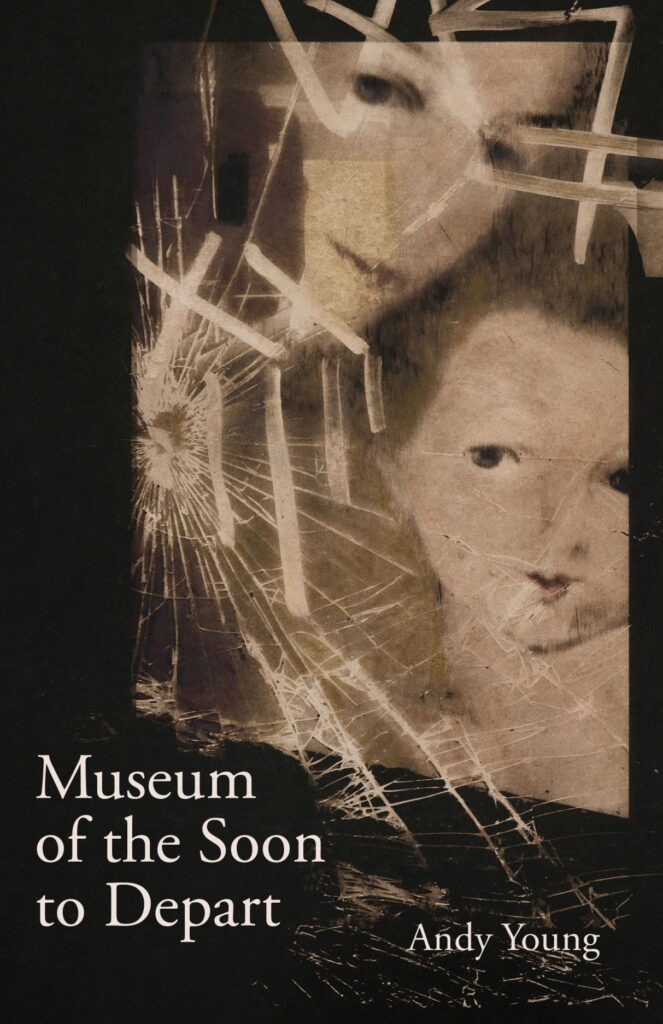

Into the portals of aninterpolated world: A review of Andy Young’s Museum For The Soon to Depart

This world, any world, is interpolated. There is a layer beneath every layer—whether seen or unseen, something holds whatever stands together. The way the world is interpolated with the multiple forces that pillar the galaxies is the same way the body works in the “Museum of the Soon to Depart.” There is a museum where the subject is also the poet, and at certain moments, we are unsure if what we are holding is our own grief or the grief of the body that we imagine to be ours, that we are taught to imagine in the tiny lights of this museum.

The dreams in the museum are haunting, as any museum that documents the history of the world would, as Susan Sontag says in her work, Regarding the Pain of Others. In “Museum of the Soon to Depart,” Young constructs a labyrinthine space where personal and collective histories intersect to create a convoluted human experience, which mirrors the physics of light, dark, and truth. This collection, divided into three compartments, “Display of Grief,” “Gallery of Pestilence,” and “Unhealed Wounds and Archives of Prayer,” serves as both archive and exhibition, preserving moments of loss in several moments while transforming to simultaneously invite readers to engage critically with the act of witnessing itself.

The opening poem, “Grief During Carnival Season,” immediately establishes the collection’s preoccupation with the juxtaposition of joy and sorrow, the individual and the collective:

I used to think I would die

of sadness but have learned there is no such luck.

So I sit by the wormy gardenia bush

as bass drum and tuba

thump through the streets—music gone

as soon as it’s heard, a gathering mist

on the unvisited graves at Saint Roch—

Here, Young deftly weaves together the sensory experience of New Orleans’ Mardi Gras with the intimate process of mourning, creating a space where personal grief exists alongside—and in tension with—communal celebration. Throughout the collection, we are stuck amongst people, silently noting the movement between language and the breakdown of chaos towards and into silence. Young’s engagement with visual art and historical artifacts provides such a rich substrate for contemplation in which she serves as the poet’s poet, inviting us into the occasion of ekphrasis in poems like “Picasso’s Kitchen” and “Botero’s El Gato del Raval” which demonstrate god’s detailed eye which extrapolates meaning from aesthetic objects. This detailed eye of the gods working through Young transforms both subject and object, humans and their collective grief into portals from which the collection takes off.

I would argue that a poet in a museum is an ekphrasis, and my argument is further solidified in “Picasso’s Kitchen,” where the speaker adopts the voice of the artist:

I will suck the bones of the fish flesh

then cast the bones in clay

I will interrogate the plums

with the sun of this bulb

even a saucepan can shout

everything can shout

And indeed, everything shouts in this collection. Even here, the poem encapsulates the collection’s broader preoccupation with finding significance in the mundane. The poet’s ability to inhabit multiple perspectives—from renowned artists to public sculptures—creates a polyphonic work that resists easy categorization or singular interpretation. In my culture, mothers throw their bodies into the ground to show the depth of their mourning—a process of total surrender, however brief, to the undeniable hands of loss, which takes and takes. This collection gives that kind of surrender—a total deliverance into the hands of a poet at a loss for self and what her eyes capture.

“Museum of The Soon to Depart” does not ignore catastrophes set in the chambers of politics. A burning world is set ablaze first in a small room. The collection draws breath from political tumult, particularly the Arab Spring and its aftermath, searingly examining the nexus between individual and societal trauma. Poems such as “Boraq on Mohamed Mahmoud Street” and “Cairo as the Counterrevolution Begins” offer a multimodal view of complicated geopolitical dynamics, eschewing reductive narratives in favor of a nuanced, polyphonic portrayal of political turmoil. Often written in either block texts, such as in “Tableau,” or in a free verse that looks disrupted, such as in “Cairo as the Counterrevolution Begins,” the poems mimic the revelation of war as unstable.

In “Boraq on Mohamed Mahmoud Street, “Young musters the image of al-Buraq, the mythical steed that carried the Prophet Muhammad:

looking back, racing forward

the Boraq can’t land her body

a funeral of faces an infant on her

back whose wings won’t work

By juxtaposing the sacred and the profane, ancient religious symbolism collides with the brutal realities of political violence. The Boraq’s inability to land metaphorically encapsulates the suspended state of revolution—a moment of potential transformation that remains unrealized. The “infant on her back whose wings won’t work” could be an allegory for the nascent democracy stillborn in the aftermath of the uprising. The poem’s fragmented syntax and lack of punctuation mirror the disorientation and flux of revolutionary moments while also suggesting the inadequacy of traditional poetic forms to capture such tumultuous events. Progressing, in “Cairo as the Counterrevolution Begins,” the poet employs a more narrative approach, grounding the political in the quotidian:

If we’d gone to Alexandria

to breathe the salt air, to be

with our friends as we planned,

we would have checked into that same

hotel off Nebi Daniel. Smelled

the burning cars yards away,

perhaps seen the bearded men

as they stormed the crowd

with machetes.

Young’s use of the conditional tense satisfies a sense of historical contingency, emphasizing the arbitrarity of who becomes a victim or a witness during political violence—both the abstract and the living are objects. This idea is further explored when the poet juxtaposes mundane details (“that same hotel”) with scenes of brutality (“burning cars,” “machetes”) to underscore or elevate the sudden eruption of violence.

The poet does not spare the reader from participating in the escape from or witnessing this violence—the poem’s shift to the actual events in Cairo using a collective pronoun/noun brings the reader into the violence happening on the page:

Instead, we stayed

in Cairo, took a drive around to see

the tanks amassing near the poll stations,

picked up some lights to wrap

around the potted fir we found.

This jarring contrast between the militarization of public space and the domestic act of decorating for the holidays creates a cognitive dissonance that captures the surreal nature of living through historical cataclysms. It also raises questions about complicity and privilege: How do we reconcile our private lives with public catastrophes around us?

Perhaps Andy Young’s use of formal diversity in “Museum of the Soon to Depart” is a metacommentary on the interpolation and distinctive differences that contemporary experiences suffer because each structure employed functions as a warden of language through the collection and our current political and personal realities. The collection features traditional villanelles and contemporary duplexes, does not avoid experimental structures, and creates a formal re-inscription that arrives at the precise location the writer intends—the poems land, with or without punctuation, at a lyrically painful, clinically sound avenue.

The “Bone Saw Villanelle” stands as a tour de force in this regard, demonstrating how rigid formal constraints can paradoxically amplify the visceral impact of political violence. The villanelle’s repetitive structure, with its insistent refrains and interlocking rhyme scheme, becomes a formal analog for the relentless, cyclical nature of state-sanctioned brutality:

My friend, an AIDS survivor, will be cut to the bone

again today. He’ll be short another digit.

Surely by now you’re a pro at amputation.

This opening tercet establishes a chilling parallelism between personal medical trauma and political violence, a connection that the poem’s subsequent iterations deepen and complicate. The repetition of “cut to the bone” and “amputation” throughout the villanelle serves multiple functions: it mimics the mechanical precision of torture, evokes the psychological toll of repeated trauma, and underscores the poem’s central metaphor of bodily dismemberment as a stand-in for political disenfranchisement. The villanelle form originates in pastoral French poetry and is here repurposed as an instrument of political critique. This formal subversion raises provocative questions about the relationship between poetic tradition and contemporary politics—how does appropriating Western poetic forms to express non-Western political realities complicate notions of cultural imperialism and resistance? To what extent does the formal “violence” done to the villanelle mirror the content it seeks to express?

Moreover, the poem’s juxtaposition of AIDS and political assassination creates a complex web of associations, linking personal medical history with broader sociopolitical phenomena. This connection invites readers to consider how different forms of systemic violence—medical, political, and economic—intersect and reinforce one another. The repeated invocation of “amputation” serves as a multivalent metaphor, simultaneously spurring the literal dismemberment of torture victims, the figurative amputation of political rights, and the social excision experienced by marginalized communities.

The section titled “Hall of Pestilence and Unhealed Wounds” nosedives into the corporeal manifestations of trauma, both personal and societal. Poems like “Pinworms” and “Fever Within” explore the vulnerability of the human body. In contrast, others, such as “Pest House Sketches: The Pest House at Jaffa,” consider historical approaches to disease and care. This section’s examination of the body as a site of intimacy and alienation contributes to the collection’s overarching inquiry into the nature of human experience in an age of medical advancement and persistent inequality. The poet’s attention to the materiality of language and the physicality of the writing process adds another layer of complexity to the collection. In “Pinworms,” the visual structure of the text on the page impacts the perception of the poem:

come out of the living at night

to lay eggs

we search our son

for pearlescent threads

in the phone light

faint smears of shit

in skin slits red crowning

the cave’s entrance

to rivers of vessel and tissue

It is the unsettled, abrupt, and uncannily brutal linebreaks. Still, this attention to language’s visual and aural qualities accentuates the poem’s (and the collection’s) engagement with the limits and possibilities of poetic expression.

As with other parts of the collection, the final section, “Archives of Prayer,” is as profound as a meditation on the convergences of faith, ritual, and mortality, situated within the crucible of political furor raging in the backdrop. The centerpiece of this section, “It is Better to Pray than to Sleep,” emerges as a magnum opus, masterfully interweaving the quotidian rhythms of Cairo with the transcendent aspirations of prayer and the immanent realities of civil unrest:

dust storms redden the sky

soon eid al-adha

feast of the sacrifice

soon the slaughter

meat in the hands of the poor

first sun

crowning

the street in a pool of blood

Here, Young’s extraordinary capacity to transmute prosaic scenes into multivalent signifiers assembles a palimpsest of meaning that demands and rewards exegetical scrutiny. Young brings sacred rituals with profane violence into the light—the Eid al-Adha sacrifice paralleled with political bloodshed—to create a tension that recants a contemporary Cairo that is, although religious, capable of descending into thick mud of political wildfire. The poem’s engagement with religious rituals directly challenges secular notions of political engagement and social transformation—by situating political struggle within religious observance, the poet interrogates the artificial dichotomy between the spiritual and the political that often characterizes Western discourse. How does this integration of the sacred and the secular complicate our understanding of resistance and revolution in the Middle East? The answers to such questions are whispered in the grief that ferries through this collection. The poet has seen and witnessed, and so we must. “The Museum of the Soon to Depart” brings us in, traps us, and asks us to become familiar with heaviness.

While often implicit, the collection’s engagement with philosophical ideas adds significant depth to the investigations and arrival happening in this poem. Existentialist concerns about meaning and responsibility in the face of absurdity permeate many of the poems, particularly those dealing with political violence and personal loss. The phenomenological attention to embodied experience is evident in the vivid, sensory details that characterize much of the work.

In the end, Young arrives fully stacked in her own grief as she shows us around “Museum of the Soon to Depart,” which emerges as a master stroke of contemporary poetry. This work chronicles the intersections of personal anguish and communal disruption and pushes the boundaries of poetic expression itself. The collection’s ambitious scope—spanning continents, cultures, and historical epochs—matches its formal innovations and linguistic virtuosity, creating a multidimensional museum that rewards repeated engagement and resists facile interpretation. The poet’s unflinching gaze turned both inward to the most intimate experiences of grief and outward to the grand sweep of political movements, resulting in a work of remarkable intellectual and emotional resonance. By refusing to draw clear lines between the personal and the political, the local and the global, the collection challenges readers to reconsider the very categories through which we understand human experience. Perhaps the most significant achievement of this work lies in its ability to navigate the treacherous waters of trauma representation without succumbing to detached aestheticization or maudlin sentimentality. Andy Young’s commitment to bearing witness—to personal loss, to political violence, to the slow erosion of cultural traditions—is tempered by a keen awareness of the ethical complexities inherent in such an endeavor. This results in deeply felt and critically engaged poetry, capable of evoking profound emotion while simultaneously inviting intellectual scrutiny.

Adedayo Agarau is a 2024 Ruth Lilly-Rosenberg Fellowships finalist, Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford University, and a Cave Canem Fellow. He is the Editor-in-Chief of Agbowó Magazine: A Journal of African Literature and Art, and a Poetry Reviews Editor for The Rumpus. He is the author of the chapbooks, Origin of Names (African Poetry Book Fund, 2020) and The Arrival of Rain (Vegetarian Alcoholic Press, 2020). Adedayo’s debut collection, “The Years of Blood,” won the Poetic Justice Institute Editor’s Prize for BIPOC Writers and will be published by Fordham University Press in the fall of 2025.