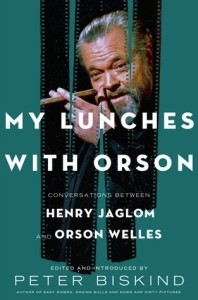

My Lunches with Orson: Conversations Between Henry Jaglom and Orson Welles, Edited by Peter Biskind. Metropolitan, 2013. $28, 320 pages.

Five hours before he died in October 1985, Orson Welles appeared on The Merv Griffin Show. On cue, Welles lumbered gamely from behind the curtain and warmly embraced his host. They retired to the dais to dish. The proceedings had the distinct air of a last round-up. Despite the cutaways to a clapping audience, late-night television had become less and less hospitable to their generation. Griffin perhaps was obligated to be unctuous but Welles clearly knew the flame was low on the wick. His wick, the culture’s wick. Griffin pressed Welles for details about his notorious liaisons with some of Hollywood’s leading ladies, including Rita Heyworth, who was then suffering from dementia. Welles tried to accommodate Griffin with kind words about his Rita but he played it pretty cagey on the whole, promising he would be more revealing in his memoirs.

Alas, there were not to be any memoirs. Perhaps if he had written them or found a ghost writer to do the dirty work, Welles might have died rich. Instead he spent his last years scrounging for work, doing televisions ads of all things. Peter Biskind’s new book, an edited collection of conversations between Welles and independent filmmaker Henry Jaglom between 1983 and 1985, reveals a Welles in dire straits. He couldn’t get financing for movies because he couldn’t secure the actors who would secure the financing. He did, however, become a staple of late-night television. But his act as a jovial bear dancing down memory lane on talk shows failed to pay dividends. Only Paul Masson and his middling California plonks came calling. “If I got just one commercial, it would change my life!… There is no “meantime.” It’s the grocery bill. I haven’t got the money. It’s that urgent…. Get me on that fuckin’ screen and my life is changed.”

Watching Welles fifteen years earlier on The Dick Cavett Show, after he had made yet another move from Europe, you have the sense that Welles felt he could use television to his full advantage, to make the case that far from being washed up, he was ready to once again conquer Hollywood as he had done with Citizen Kane. In the clip below, Welles, every bit the mirthful potentate, takes on Cavett. Their wit, erudition and completely unpretentious ease with “high culture” astounds and charms. Those were days, even if the kids were realizing they were never going to paint it black while Nixon was cravenly sopping to his Silent Majority.

Welles is hardly a tragic figure. He rages good and proper against the dying of the klieg lights in Biskind’s book. As in his conversations with Peter Bogdanovich, Welles reveals himself to be a shrewd and insightful critic of Hollywood as a factory. He rants and raves against the advent of the producer, in particular Irving Thalberg whom he calls “Satan.” Although he was able to have his way with Citizen Kane, Welles soon learned that a director was little more than a puppet of the producer in the Hollywood studio system. The moguls used producers to control the movie all the way to the box office, as evidenced by his legendary rumble over Touch of Evil (1959). Things weren’t much better when Welles left Hollywood for Europe. As hard as he hustled investors and producers, they hustled him.

Finally figuring out that producers and audiences were no longer interested in arty renditions of Shakespeare, Welles turned to the cine-essay. If his film, F is for Fake, had been a financial success, even a modest one, Welles could have become the Chris Marker of America, making the small pictures he wanted and keeping the wolf from the door. Next to Citizen Kane, F is for Fake was Welles’ favorite film.

But his timing was off. Welles was in self-imposed exile in the late sixties and early seventies when the creative producers like Robert Evans managed to keep their corporate bosses at bay while offering directors like Roman Polanski full control of their pictures. Biskind’s seminal study of that period, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls looms large over this book. One is left wondering if Welles, well-connected to producers and agents via Jaglom, simply had lost his mojo. He was a man too long in the tooth and too brittle to bend to new realities. One day, Jaglom introduces Welles to a female producer from HBO and the great man chases her away from the table when he learns that she wants him to make a half-hour serial set in a tropical resort.

Orson Welles came back to America but America never came back to him, and he died with the Rosebud that had sustained his quixotic dreams for so long—a typewriter—in his lap.

Stirling Noh, a Canadian author living in London, Ontario, writes existential novellas and erotic urban fiction.