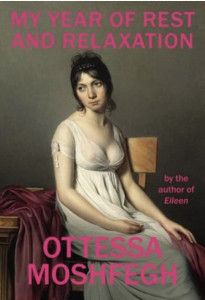

My Year of Rest and Relaxation, by Ottessa Moshfegh. Penguin Press, 2018. 304 pages, $26.

My Year of Rest and Relaxation is the story of a nameless young woman as she attempts to engage in a year-long experiment in cognitive avoidance. Her goal is to sleep for an entire year—a passive but painstaking marathon. The protagonist consumes a wide assortment of prescription pharmaceuticals, not to remedy but to blanket. Her desire is to escape and release all attachments—her relationships, her history, her thoughts—into a blank and indifferent haze.

Ottessa Moshfegh’s protagonist is sharp, weak, and desperate—qualities she passively observes and actively escapes through sleep. There is a passion only for her year-long experiment attached to nothing except her floating routine, her VCR, and her pills. A recent Columbia graduate, the narrator resides in a large, white apartment on the Upper East Side, living off of an inheritance from her recently deceased parents. Through her experiment, her days become a blur, characterized by a dysfunctional and ill-defined circadian rhythm. Her only breaks involve listless movie watching, walks to the bodega down the street, and more pills. She describes her endeavor as follows:

I was finally doing something that really mattered. Sleep felt productive. Something was getting sorted out. I knew in my heart—this was, perhaps, the only thing my heart knew back then—that when I’d slept enough, I’d be okay. I’d be renewed, reborn. I would be a whole new person, every one of my cells regenerated enough times that the old cells were just distant, foggy memories.

The novel paints sleep as the ultimate luxury and vice. The narrator vividly describes hazy childhood mornings with her late mother—describing them both as somnophiles, who wouldn’t budge at the sound of the alarms for school each morning. The narrator is aware that her mother was taking her own assortment of medications and sleeping aids, and questions whether her mother was drugging her as a child. She reflects on these memories as the only real bonding time spent with her mother: “She was not the type to sit and watch me draw or read me books or play games or go for walks in the park or bake brownies. We got along best when we were asleep.”

She loses her father to cancer, and her mother to an intentional overdose only months apart. This is the cherry to top a childhood characterized by cold indifference from her parents. This culminates in an adult life that is none the better—her relationships are exclusively with a degrading ex-boyfriend, an unhinged psychiatrist, and a single friend who visits frequently, only to be put at the mercy of the protagonist’s jarring dissections and cruel, mental dialogue.

The reader views the main character as isolated, alienated, and disconnected from humanity. She is crass and hateful, with biting criticism for everything around her. We see the early family dynamic as calibrating, informing our place in the world, providing a baseline comfort. We see the dissonance produced in the person who lacks such comfort. We might liken her to a John Cheever character, as in The Swimmer: “gone was [his] navel, and what…would the roving hand make of a belly with no navel, no link to birth, this breach in the succession?” We see her rejection of the art scene in which she was immersed right out of college, painting it as canned and vapid and so far removed from the spiritual lifeline it could have been. Through her frustrations, she both reinforces and is forced into her role as stranger.

We witness one of the forms in which mental illness transcends class boundaries, heavy and looming in the sterile white apartment. We see access to resources as providing both health and ill-health. We see sleep painted as simple and primitive, but not afforded in such degrees to others. The friend Reva, from a lower-middle class family, for example, both envies and pities the protagonist. Reva must deal with her own self-hatred, her own loss of a parent; but we wonder if her advantage lies in her inability to go to such reclusive measures. Our narrator, on the other hand, lacks such connections, lacks a world to be a part of, lacks real ground to plant herself on.

We are graced by a complex protagonist who we are sometimes disgusted with but are still rooting for. As readers, we can see through her cynicism to the pained person underneath. We may not trust her methods, but we know she is leading us somewhere important. Despite the subject matter, the novel is rife with humor—often dark and absurd—providing tincture. The interactions between the narrator and psychiatrist—who is a quintessential “quack”—are some of the comedic highlights of the book.

Not surprisingly, the attempt to become a blank slate has an inverse effect. As the year goes on, we read a heartfelt lifetime of reflection, and a rich inner-life that refuses to be quieted. Over time, the narrator gently, and sometimes very fiercely, gets to unpack years of her discordance. Her apartment and excess of sleep creates a blank canvas with which to work on.

In the last of her binges, we weave through weeks of free-association brought on by the ingredients on the back of a shampoo bottle. Does her thinking become sharper or more convoluted? She moves through words, memories, and concepts, dancing around but eventually moving closer to some sort of redemption—a story of muck and spiritual cleansing. The novel asks, is the key to transcend or lay comfortably with your demons? When are the two acts simultaneous?

Mikaela Dauber is a student at Loyola University New Orleans.