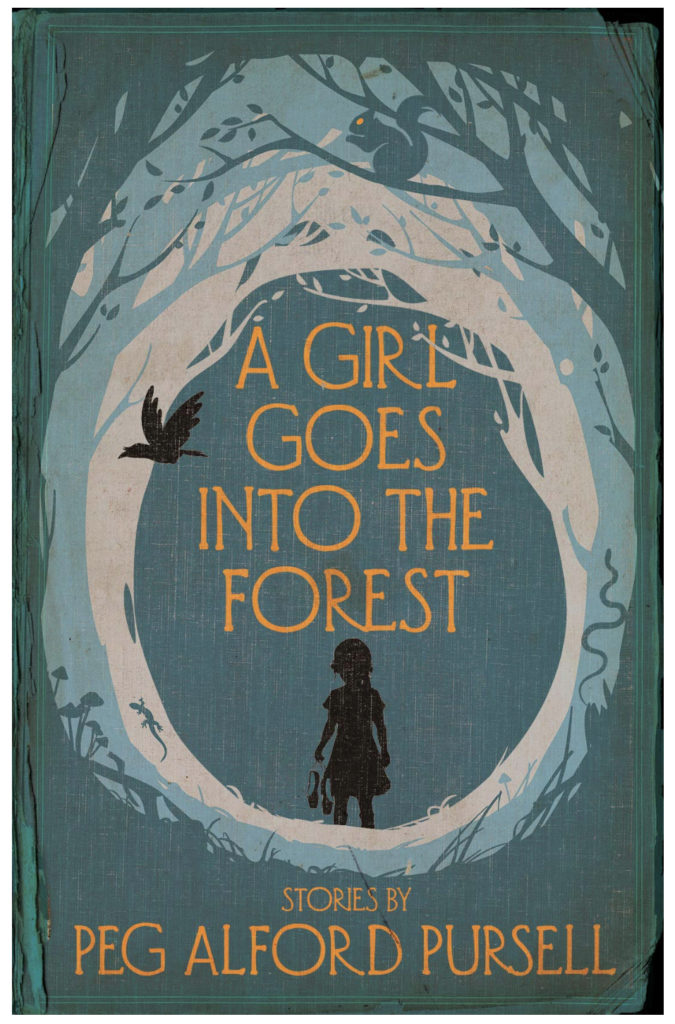

In A Girl Goes into the Forest (Dzanc Books, 2019), award-winning author Peg Alford Pursell illuminates the many faces of love and loss in 78 cross-genre stories and fables. Each hybrid flash immerses readers in the complex desires and sorrows of daughters, wives, mothers, as well as sons, husbands, siblings, and artists. In forests both literal and metaphorical, the characters try, fail, and try again to see the world, to hear each other, and to speak the truth of their longings. Described as “a string of pearls and as complex as a thousand-piece puzzle” by Ramona Ausubel (Awayland) and “a pitch-perfect condensation of moments” by Karen Brennan (Monsters), Pursell’s stories call up a world at once mysterious and recognizable, a world where “no one can deter a person from her mistakes.”

Peg Alford Pursell is the author of Show Her a Flower, A Bird, A Shadow, which was the 2017 INDIES Book of the Year for Literary Fiction and featured in Poets & Writers’ 5 Over 50 Reads of 2017. Her work has appeared in Permafrost, The Los Angeles Review, Joyland Magazine, and other journals. She is the founder and director WTAW Press and the national reading series Why There Are Words.

NEW ORLEANS REVIEW

While reading A Girl Goes into the Forest, I was often struck by the various ways each story exists as its own unique organism as well as composes the larger fabric of the collection. Can you say a bit about what it means to envision 78 pieces of your writing as one manuscript? I’m curious if plot, arc, or theme were important considerations or obstacles during the curation.

PURSELL

All of these elements played a role, for better or for worse. Initially, my desire for the collection was to simply find a way to organize it so that the longer stories fit in, since most of the works are short to very short. Finding or creating a rhythm was essential so that one can move from a series of very short stories (or hybrids) to a twenty-page story and then back to another sequence of one- or two-page stories. It took me some time to come to the organizing principle of using lines from “The Snow Queen”—a story that had, in my mind, cast echoes into my stories—to delineate the book’s sections. Once I paid attention to this idea, it was easier to structure the book overall.

NOR

I did notice the phrases from “The Snow Queen,” and also the way certain section titles act as benchmarks for the subjects within the surrounding stories. For example, the prologue begins “tentative, curious, uncertain, alive” but the first story after the section title is already mourning “the chance to tell her one day.” I couldn’t help but read the section titles as transitions in a life—the collection ends with “Note to a Ghost,” when the tentative and uncertain become “beast, bird, botany, being—all knowable.” This oscillation between life and death, knowing and unknowing—is “Note to a Ghost” a newer story or did the loss of the Girl from the collection’s title always give way to knowledge of the Forest?

PURSELL

“Note to a Ghost” isn’t a newer story—it appeared in 100 Word Story in January of 2016 and was later anthologized in Nothing Short of 100. I love your idea of seeing the Girl as lost after she acquires first hand knowledge of the Forest. It seems to me that knowledge means a loss of one sort or another—or maybe better thought of, it’s a transformation or transmogrification that happens with gaining understanding.

NOR

And perhaps knowledge beckons a loss of innocence or youth in that transformation. There also seems to be a grief for previous selves—the self and identities as defined by lovers, families, and others is a frequent concern for your characters. I understood this concern especially while reading your story “Starflower [I want her back].” In that story, there’s simultaneously—between bracketed and unbracketed language—an appreciation of the self and a yearning for the other all contained in the same narrative.

PURSELL

Thank you for this reading. Characters are never all one way or another, as of course, people aren’t. An acceptance or even embrace of one’s identity, especially one that is hard-earned (as in Gerda’s quest to save Kay, whom she intuits is alive, somewhere out there in the big wide world—a reversal from many traditional fairy tales, in which this girl has agency to rescue the boy, rather than be herself rescued from whatever fate has been assigned to her), it doesn’t cancel out longings for what might have been or for what has been. That’s simply the non-binary nature of people, the infinitely complicated compilations of ourselves, replete with and driven by conflicting ideas, feelings, thoughts. We contain multitudes, as one well-known poet wrote. With luck, my characters are true to human nature in that way.

NOR

They are, and I believe it was their humanity that often led me to enjoying your collection one story at a time, whether the piece was a few pages or only a few sentences long, and linger afterwards in the emotions and images of that story space. Then when I read multiple pieces at once, I recognized the ways neighboring stories echoed or reflected each other, adding in concert a beautiful and heartbreaking kind of nostalgia. Are there certain emotional textures or dynamics you find you return to in your writing and that are particularly essential in A Girl Goes into the Forest?

PURSELL

Every book or manuscript is different, of course, and I’m not particularly conscious of the textures, territories, or dynamics I’m drawn to exploring when I’m composing. In the case of this book, though, after the writing of several of the stories I became aware that I was writing through the sense of loss running through me during that time period. The losses are really the experiences of transition, the inevitable living of our lives: our parents age, our children grow, our relationships strain or break and new ones form, grow, transform.

It’s impossible for me not to write about the experiences of girls and women in our culture. In America. Hence the epigraph: “Well she was an American girl, raised on promises.” It was 1972, I think, when Adrienne Rich wrote “Diving into the Wreck.” How far we have not come. And because we are living currently in a time when the destruction wreaked by the patriarchal system is clear, it was impossible not to write (though to a lesser extent) of experiences of boys and men. Here, I’m thinking of what bell hooks wrote: “Learning to wear a mask (that word already embedded in the term ‘masculinity’) is the first lesson in patriarchal masculinity that a boy learns. He learns that his core feelings cannot be expressed if they do not conform to the acceptable behaviors sexism defines as male. Asked to give up the true self in order to realize the patriarchal ideal, boys learn self-betrayal early and are rewarded for these acts of soul murder.”

And here I’m thinking of little Kay (the boy in “The Snow Queen”) who gets a piece of the magic mirror in his eye and one in his heart: “He was soon able to imitate the gait and manner of everyone in the street. Everything that was peculiar and displeasing in them—that Kay knew how to imitate: and at such times all the people said, ‘The boy is certainly very clever!’”

NOR

Those patriarchal masks and ideals—I’m remembering now your story “My Father and His Beautiful Slim Brunettes” and how the father character was the narrator’s James Dean before she knew who James Dean was. It seems the father has that same mirror in his eye and heart as Kay, and the father not only wears the mask, before the end of the story he also perpetuates and expects the same self-betrayal in others—like how the father and son share a car to pick up girls and the grandson is told to shout to be heard. Of course, the women in the story suffer whether they conform to the father’s expectations or not, and the last hope is a child with “a spark of an idea about how he could be.” Is this hope how, do you think, we finally get some names in Adrienne Rich’s “book of myths”? I’m thinking about how soul murder can be countered by creativity, and especially by stories that spark ideas of how things could be.

PURSELL

The father in this story has the mask on well before it begins, and continues to perpetuate and demand the same of the son and grandson, yes. He knows and sees no other way—this is what the world seems to demand of a man in this story—and the longing and yearning his daughter senses he experiences seems to be expressed in his desire piqued by the beautiful country music vocalists. On the one level, it can be presumed that this arises from that male gaze, objectifying their female beauty—and as dangerous to him as the mythical sirens in the seas were to ancient sailors.

Perhaps there is another deeper level to his yearning: for their artistic expression, their ability to create and perform music, something that eases his soul, and maybe he wishes he were able to do that in a different kind of world than his own, and his daughter picks up on that, that which he doesn’t allow himself. Her visit home—the action she’s compelled to take—is a kind of testing the waters: what will her father see in her, a musician who has this recording contract (a legitimizing of her talent and agency), a young woman who’s embodied his longing for expression? He isn’t able to see her, not really—the mirror is in his eye—but the hope, as you say, is for the grandson, a little boy who she lets know can be heard just fine as he speaks. Whether the spark of hope she, as the outsider, gives to the boy will be enough in the long run is anyone’s guess. But it exists, she gives it, and with it there’s reason to hope for more for this child.

NOR

And I think the following stories in A Girl Goes into the Forest satisfy that hope for more. There is a lot to appreciate in your stories, both in content and in form, and I noticed a lot of your stories first appeared in literary journals dedicated to genre bending. Are there certain aspects or constraints in short form writing that you find especially useful to your creative processes and different emotional explorations?

PURSELL

Thank you! Constraints have always been useful to me in writing. They seem to operate in a way that gives the parts of my mind that are filled with doubts—that run over again and again the utility of the act of writing, that undermine the pleasure of creating, like hands on worry beads—something to do. Worry beads, unlike prayer beads, have no ceremonial or otherwise significant purpose other than to keep the hands busy. Likewise those thoughts, too, need to be kept busy, and using constraints, such as imposing word limits, for example, fulfill that purpose. That’s my current theory, anyhow.

NOR

Interesting, your theory reminds me of a friend who—a few years back—set a goal for herself to write for thirty seconds each day. It’s hard to sit down and write, even without the sometimes-unending worry beads, but thirty seconds was a way for my friend to keep practicing (she usually wrote longer than thirty seconds once she got going) and also parry doubt with a sense of accomplishment on the days when only thirty seconds of writing was possible. Constraints in this way, and the way you describe, seem to strengthen rather than limit the authorship. Are there authors of short form or constraint-based writing or genre-bending works who you admire, or who were especially influential when you were writing A Girl Goes into the Forest?

PURSELL

I like your friend’s ritual and understand it very well. Similarly, at a time when I most needed to, I imposed a ten-minute writing routine on myself daily. In the workshops I taught I began each with that same writing constraint, reminding students that diamonds are simply are form of carbon subjected to pressure, to heat. Likewise, they created within those ten minute spans, gems I remember, and in some cases have seen expanded, revised, intensified years later.

It’s difficult to pinpoint influences; it’s much easier to discuss writers I admire. Virginia Woolf was the first with whom I felt a deep affinity, and continue to, whom I continue to reread. Just now I’m reading Amy Hempel’s Sing to It, and I’m reminded of how her earlier stories, now all collected in one volume, spoke to me. Mary Robison. Noy Holland, Nin Andrews, Karen Brennan are queens of genre-bending work. As are Diane Williams, Renee Gladman, Eula Biss, Soma Mei Sheng Frazier. The list is long!

Thea Prieto writes and edits for Poets & Writers, Propeller Magazine, Portland Review, and The Gravity of the Thing. Her writing has also appeared at Longreads, Entropy Magazine, Yalobusha Review, The Masters Review, and elsewhere. To learn more, please visit theaprieto.com.