-

Philip Himberg -

Lisa Ahima

Philip Himberg oversees the creative mission as well as the financial well-being of the nation’s first multidisciplinary residency program. Himberg arrived at MacDowell in May of 2019 from The Sundance Institute where he spent 23 years guiding all aspects of the Sundance Theatre Program, including its Theatre Labs and satellite residency programs in Massachusetts and Wyoming, and internationally in several locations in East Africa, the Middle East, and North Africa. Under his aegis, the Institute’s Theatre labs have supported many hundreds of playwrights in the creation of important new work, which is produced across the U.S, off and on Broadway. Himberg is also a playwright, and his most recent play, Paper Dolls, had its world premiere at the Tricycle Theatre (now Kiln Theatre) in London in 2013. He is a former member of the Tony Award Nomination Committee, served as past president of the Board of Theatre Communications Group and was a trustee of the Kiln Theatre, London. He has taught at NYU/Tisch and the Yale Drama School. In addition to a B.A. from Oberlin College, Himberg holds a degree as a Doctor of Chinese Medicine, and previously was a practicing acupuncturist and herbalist.

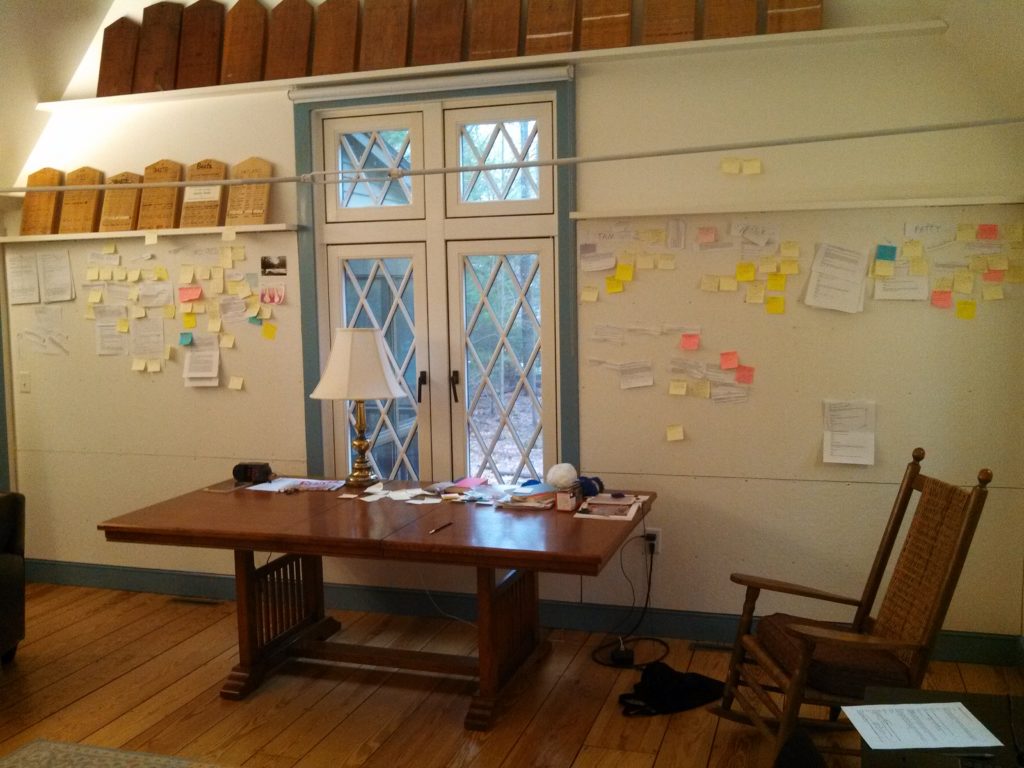

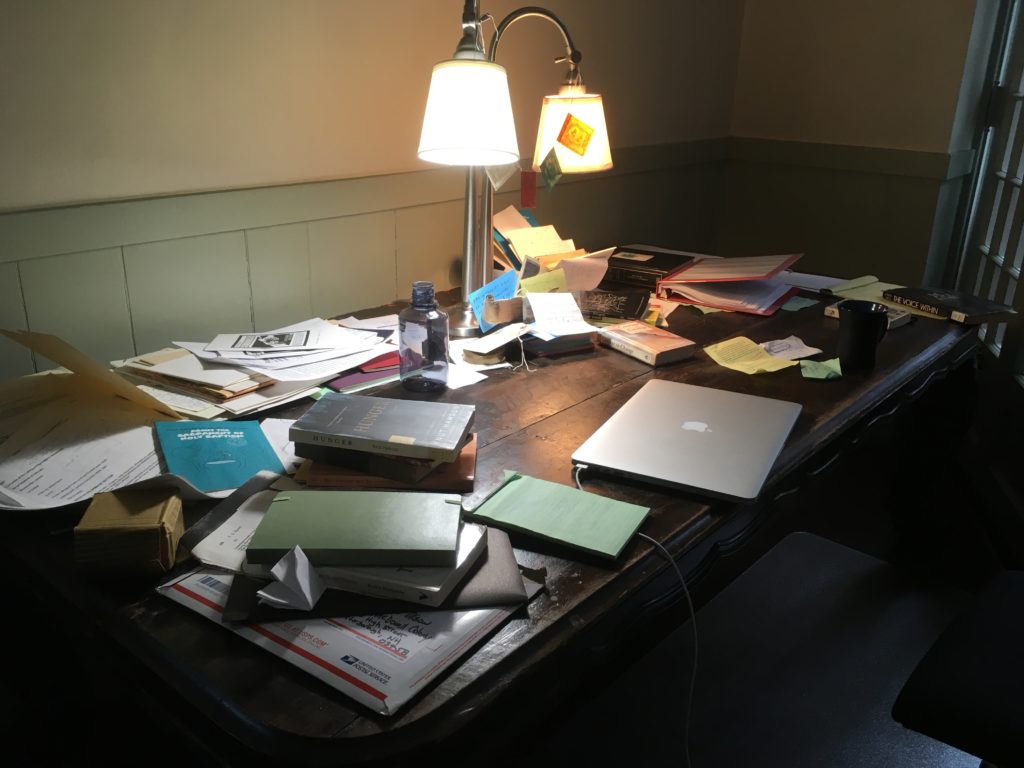

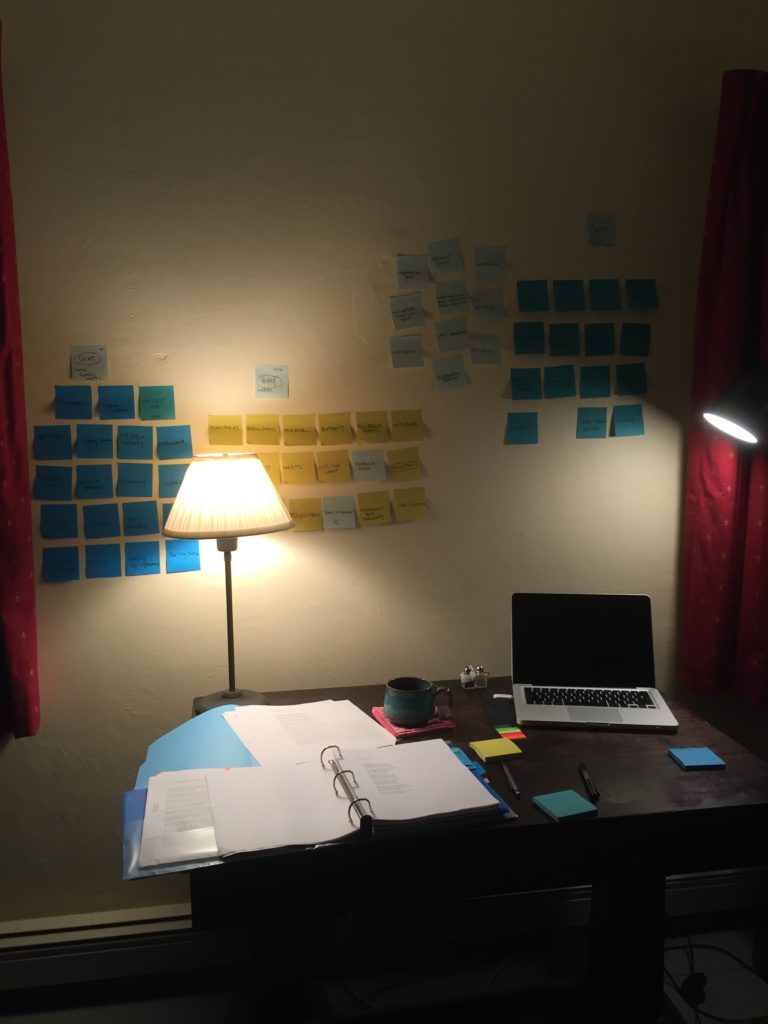

***Editor’s Note: Throughout this interview, you will find photographs taken at MacDowell by queer fellows while in residence.

New Orleans Review

Can you talk about how your love for theater developed?

(Literature, Fiction), 2017

Philip Himberg

My love for theater felt like it was almost inborn. I grew up outside New Haven, Connecticut, and I recall as a young kid doing puppet shows and wanting to be in that world of making up stories. I used to write plays as a six or seven year old. I used to stage them in my backyard with sheets on the clothesline.

New Haven is a very unusual town for its size; it was only about 50,000 people, but it had two regional equity professional theaters by the time I was a teenager, so in that way, I was also exposed early on. We were only about an hour and a half on the train from New York. When I was old enough to lie to my parents and say I was going on the train to New Haven to go shopping, I would go on the train to New York with my friends, and we would see shows.

It was always sort of in me. I found it was the most provocative way to be myself, whether it was acting, writing, or whatever. I was also very lucky. In high school, I had an extraordinary drama teacher I am still in touch with. She’s in her 80s now. We weren’t doing silly musicals; we were doing very serious theater like Antigone. Not just Bye Bye Birdie, what have you. Then, I went to college at Oberlin in Ohio. This was the early 70s. There was a lot of experimental theater: Grotowski, psychophysical theater. One of the great leaders in that field, Herbert Blau, had moved from CalArts, where he had created an interarts program. I was part of his company as well. In that company, there were people like Julie Taymore and Bill Irwin. It was a wonderfully rich time.

The only other thing I’ll say about my younger years is that during my sophomore year at Oberlin, there was an opportunity to come to New York for one semester to get full theater credit and to work as an intern for a professional theater company. That changed my life. When I was 19, I was working for something called the Chelsea Theater Center, which was then housed at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, doing very extraordinary, European and American work. I was also exposed to so many amazing groups of people and was able to get a job in the professional

theater at Playwrights Horizons, which was just beginning its rise to becoming a playwright’s theater. That encapsules my earlier years.

NOR

Did you find it difficult navigating the business side of theater as a gay man?* What are some surprising experiences you’ve had?

Himberg

In terms of being a gay man, I felt very safe in the theater. I felt very accepted about my sexuality in the theater. I never felt I had to hide it, certainly after high school. I also went to a college where there were a lot of queer people. The business side as well; I don’t think that I struggled very much with that. There was a period of my life in my thirties and early forties where I left theater, went back to school, and I became a doctor of acupuncture and Chinese medicine. I did that for over a decade. I was one of the few out, gay accupunturists in Los Angeles at the time, at the height of the AIDS crisis, and I was treating a lot of very sick men. I do recall that in that profession: being a healer, doctor, and physician, it was suddenly like, oh, if a patient would say to me, “What does your wife do?” there was this moment of, “I have to come out to this person and say that I’m gay or I have a husband or boyfriend.” I thought, “Wow, that was never a problem for me in theater.” I don’t think the business in theater, at least in New York City or Los Angeles, was a place I felt I had to hide it or that I felt uncomfortable about. I only realized that when I was in another profession for a while. People didn’t assume I was straight in the theater, but they did when I was a doctor.

In terms of other surprising experiences: having a child. You have to be out because you’re not going to have your child imagine that you’re not who you are. She made us be completely out. If we went out and people saw me pushing her in a stroller, and a stranger would say, “Where’s your mom?” I’d have to say, “She’s being raised by two guys; we’re gay.” I had to always be out for her so she would always be proud of her parents.

NOR

In performance art, some people may argue that you learn a lot about yourself as well as what you’re portraying. Do you think there are some parallels between navigating your identity as queer and performance art in that regard?

Himberg

Absolutely. There are two kinds of artists here: there’s the artist who don’t define their art as “queer art” but who aren’t closeted. Their art is expressive of their queer being for sure. Then there are a lot of queer artists who explicitly and implicitly do “queer art.” I think many of my friends who are out and doing performance artwork are explicitly and emphatically expressing queer art in some way. My closest friends are people like Taylor Mac. I’ve supported so much theater work in my life by queer artists. Even if the work isn’t a sort of celebration of the queer body, it’s work that has an aesthetic or a point of view or a lens that is definitely queer. I suppose, because I am myself, I am just interested in that work. It’s not that I think it’s all great. Sometimes I think it’s terrible, but I certainly want to be able to see it. Growing up, I didn’t see myself much. I was closeted until I was 23, which is pretty young for my generation. It was pretty torturous. Even after that, it was really difficult. I can’t think of a performance artist who is queer, or identifies as queer, who’s work isn’t in some way an expression of that. I’m probably wrong; there probably are, at least in performance art in particular. Performance art is so on the surface. It’s your body. It’s your voice. It’s yourself

NOR

Favorite plays and playwrights?

Himberg

Oh, God. In terms of the canon: Tennessee Williams. We had lovely correspondence together which I treasure. I’m a huge fan of Tony Kushner. Jeanine Tesori and Lisa Kron are good friends of mine. We developed Fun Home at Sundance. I love Lisa’s playwriting. I love Taylor Mac. That’s such a hard question. I have so many plays and playwrights I love. Back in the day, Charles Ludlam was a very seminal artist for me. For more contemporary work: Branden Jacobs-Jenkins is someone who’s work I love, as well as Jackie Sibblies Drury, and Lynn Nottage. There’s Ayad Akhtar who wrote Disgraced. Then there’s Doug Wright, who wrote I Am My Own Wife. I also love Michael R. Jackson’s A Strange Loop. I’m a huge fan of his work. I think he’s pretty out there. A Strange Loop is one of the best plays I’ve seen in the last year.

NOR

There’s this weird dichotomy between forced isolation with the pandemic and intentional isolation with artistic residencies. What are your thoughts on that? What’s the difference between those two for you?

Himberg

Intentionality. There’s no doubt MacDowell, like many artist residencies, is built around the notion of isolation. People come to get away, and when they’re there, they spend probably 80 to 85 percent of their time in isolation in the sense that they’re in their own studio. Their lunches are delivered to them purposefully so that they don’t have to disturb that alone time. The one piece that is requested but not demanded is that at dinner time, people come together and share a meal. When you talk to the artists after they’ve been at MacDowell, even though maybe about 85 percent of their time has been making work whether it’s writing, sculpting, or what have you, 15 percent has been those dinners. After those dinners there’s also sharing work. Many of them will describe the experience at MacDowell as 50/50. I think the time spent in a community listening, learning, sharing ideas, and making discoveries about how their work connects feels as important to the residency as the time they spent making their work. I’m sure it’s different for different individuals. People will say, “I valued those eight weeks,” if it’s that long, “to be on my own.” Some may say, “I made my best friends for life. I’m collaborating with someone now I never knew existed.” All in all, I think people will talk about both sides of it. But they’re intentionally coming. They’re coming to a bucolic, rural atmosphere that’s far from where many of them would call home, because many people come from urban atmospheres. Maybe they have families and other responsibilities or other work.

It’s interesting, this notion of isolation. We created, when the COVID pandemic began, something called virtual MacDowell. I wouldn’t call it a residency; we just call it virtual MacDowell. Although we had no clue if anyone wanted to do it or what it would actually be initially, as we designed it with artists, it ended up being a community online. It was eight sessions over a month. We did one pilot; we’re going to be doing more. We chose artists who had been admitted to come to MacDowell in the spring and the summer but couldn’t physically come. We told them this was not going to substitute ‒ they would still come when we reopened ‒ but would they be interested in an online version? We got 8 people across all of our disciples, and they met twice a week, 90 minutes at a time. We designed with alumni on what that would be. You had the community coming together. It was really about artists having the opportunity to talk to each other, to ask hard questions, talk about process, talk about COVID, talk about politics, talk about Black Lives Matter. Whatever they needed to express. And at the end of that month, as it ended in August, we were shocked at how enthusiastic people were about that offering.

We thought they would say, “Yeah, thanks. It was okay,” but instead, we got a new perception of what it meant to them about being together. We got a new understanding of MacDowell. Both sides of that isolation question are fascinating to me. We are reopening MacDowell at the end of October with just eight artists to start. We’ve been vetted through doctors and epidemiologists: wraps and wraps of people about how to do this. What everyone said was, “Well, you’re perfectly set up because you have these separate studios. You can provide healthy, safe isolation.” What we can’t provide is the dinners together, so all their meals will be delivered. So, it’ll be interesting to see how that works.

What I am interested in virtually every artist I know needs to work at some point on their own. Now, in theater, of course, and dance, that being in the room collaboration is implicit in almost every case. There is a huge conversation we could have about the inability of theater artists to make work together in a room right now and how devastating that is for the community. But as a playwright, you probably need the space. As a composer, you need the space. As an actor? Not so much. Actors need and want to be in a community in realtime and real space. We can make all kinds of work online, but ultimately, a stage is that sacred place where actors gather and an audience gathers in real time too which is another piece of it.

Another thing about this is some people have thrived in isolation and found that they were able to do work, and others were stuck completely. I find that interesting because not every artist is obviously the same. I’ve spoken to people who’ve said, “I haven’t written a word. I haven’t written a note.” Or, “I wasn’t able to write a note for three months, and then I started.” And others have said, “My God, I loved it. I was able to get so much work done.”

NOR

How have your goals shifted for MacDowell before the pandemic and after?

Himberg

I don’t know why I find this question so moving, but I do. It’s not that the goals have really changed tremendously. I came into this organization only about 15 months or so ago. There wasn’t really a strategic plan in place for me at MacDowell, but there was a little road map. One of the most important pieces of it was how to understand the ways in which MacDowell needed to be brought forward around issues of diversity, inclusion, access, and equity. I came in with the idea that there was work there that had to be done, and I did that successfully at Sundance. What has changed is the world has shifted and the movement toward anti-oppressiveness and anti-racism has accelerated, as it should, soon after I arrived. Then there’s the pandemic on top of that. I came in and immediately hired a remarkable group of people who are experts in this field of diversity, inclusion, access, and equity to work with us. All of that work took on a very different intensity. The work asked a lot of questions around who is in the room at MacDowell, who makes decisions, who has power, and how does that manifest? I ask those questions absolutely 65 percent of the time that I’m here. It’s also interesting, to be perfectly honest, as an older white man at this moment to be in a position of leadership at a cultural organization. So all of that, as it is always in the ethos of my mind, is much more clearly in front of me right now. I’ve always said that I was going to be a bridge executive director. I want to find a way to organically, with my staff and board, change the culture of the organization so that it would be ready for new leadership. I’m of a certain age, and this is what I want and need to do. The spine of everything I do on a daily basis is to understand, learn, honor, and be willing to do the work that entails, along with an incredible body of people who want to do the work with me.

My aspiration is that artists have a place at the table of our democracy. We have opinions from financial experts, corporations, scientists, technicians. Where is the artist in these conversations? I really believe that artists are the most important leaders because those are the people who are actively doing the experimentation and taking risks. Those are the bravest and most courageous people whether they’re writers, painters, or musicians. If they don’t lead us or are given the opportunity to do so, I worry about us. Here’s the bigger aspirational goal: how do we amplify the voices of these artists who come from multiple narratives from multiple landscapes so that the conversation at the table is really rich and full of creative tension and complicated so that we are truly representative of this world? I have to ask myself how I live up to that aspiration every day. I don’t always have the answer. I don’t always feel equipped. But that’s what’s motivating me. What makes a residency a good residency? It needs to make sure the artist at that table helps represent what I just said. The conversation has to be rich and exciting and full of possibilities. With a board that’s older, has been amazingly supportive, and has grown this organization, is it the right board for ten years from now? I juggle with questions like, “Here, I have a decision that needs to be made; who needs to be in the room to make it? How are we coming to a consensus on these decisions?”

Interdisciplinary), 2020

NOR

Do you think asking these questions works in favor of dismantling systemic oppression for MacDowell?

Himberg

I think that’s the goal. I think that, like everyone, I have a learning curve in terms of the awareness of my own privilege. Touching back on your question about how I got into theater: I had the luxury, even coming from a lower middle class family, to appear white in society. I’m Jewish, I’m queer, I’m married to a Muslim. I’ve had an enormous privilege to make the choices I did and to be in the places I go. I’m aware of that. I’m aware of the system that made that possible and the system that makes that difficult or impossible for other artists and people. I can’t say that everyone inside the MacDowell institution has that same understanding. Some people do and some do not. MacDowell itself is in southern New Hampshire, and New Hampshire is one of the whitest states in the union. You’re bringing people there who go into this beautiful little town, but there’s no one who looks like them there. What is that about? A lot of artist residencies tend to be in some rural environments where that’s also true.

The Alliance of Artist Communities, AAC, the umbrella organization for most artist communities, is run by an amazing woman named Lisa Hoffman, who happens to be African American. She’s been very extraordinary and fierce lately about the responsibility of these residencies. A lot of these places, including MacDowell, are built in places that were originally Native land. So what does that mean? To me, it’s not enough to stand at the dinner table and thank the Abenaki nation for being on their land. What are we doing for Native artists? How are we creating access for those people who don’t know about us, or if they do, might think we’re not for them? What we’re doing right now is we’re creating partnerships with various communities that are meaningful partnerships. Not just, like, hey, let’s get some Native Americans to MacDowell. It’s more like: what is it as an Indigenous artist that you need and how can we be able to partner with you in that way? One of the best examples is that we’re having our national gala coming up in a few weeks. It’s usually a big party in New York, but of course this year it’s virtual. What we’ve chosen to do is to honor Ava Duvernay. We created this award called the Marian MacDowell award for artistic visionaries. Ava’s going to be our first awardee, but it’s not just an award. It’s a partnership with Array, to further spaces for Array artists to be at MacDowell. That’s just one little piece, but that’s the way in which we’re trying to move. It needs to be led by artists of color, Indigenous artists, queer artists, trans artists, artists with disabilities.

NOR

Can you talk more about your decision in removing “colony” from MacDowell, and who was active in that choice?

Himberg

I knew from the day that I arrived that I didn’t like the word “colony,” but you don’t start a new job and say you should change the name of your institution. It was a confluence of things that led to the actual decision. Soon after George Floyd’s murder, I got a petition from my staff. At first, I was like, why are you sending me a petition? I’m not on the other side of this one. But it was a really great tool. The petition wasn’t handled entirely the way it should have been; not everybody felt a part of it. In any case, there was a petition, which created a kerfuffle. I called our board, and they said, “There’s a petition, but aside from the petition, there’s a real issue here.” I was

nervous. The board is big; it’s 60 people. There are some younger, some older people on the board who’ve been there for decades. We began a process where we almost one-by-one, in groups, had conversations. I hoped that for people who didn’t understand, that there would be an “ah-ha” moment. Virtually, for everyone, there was an “ah-ha” moment. The moment was really about the artists who are leaving MacDowell coming to us and saying, “The word colony is confusing to me because it’s such a brutal word and it hurts me. I don’t know why it’s necessary.” I think once people understood that it was a hurtful word to the people we were built to service, there wasn’t a whole lot of conversation. There were some people who would say, “Well, I’m an artist, and the word ‘colony’ has other meanings. Are you telling me that I can’t use it around my love for bees or the fact that I study medicine?” I’ve said, “You can use it anyway you want but MacDowell cannot use it anymore.” Because even if it means other things, it is a hurtful term. The staff, my leadership group, and the board came together, and really within two weeks, there was a unanimous vote to remove it. Then we got some hate mail. There wasn’t a lot of that. We mostly got a lot of support. It was a small step in a way but language does matter. I thought it was an important step.

NOR

Do you think it’s necessary for communities such as MacDowell to be held accountable for sociopolitical issues?

Himberg

I do. I don’t think I can speak for the board and the staff, but I do. I don’t see how they aren’t inextricably one. I don’t believe that artists need to do social justice art. I don’t think they need to be told what to do. I think artists should do everything and anything, but I do think art is pretty political by its nature. While I don’t think we’re a social service organization, I think we are a cultural organization. We don’t take “sides,” politically speaking. We do advocate for artists and for freedom of expression. That makes us, in some circles, political, but in others, probably not.

NOR

What do you think it means to uphold MadDowel’s legacy? What is that legacy?

Himberg

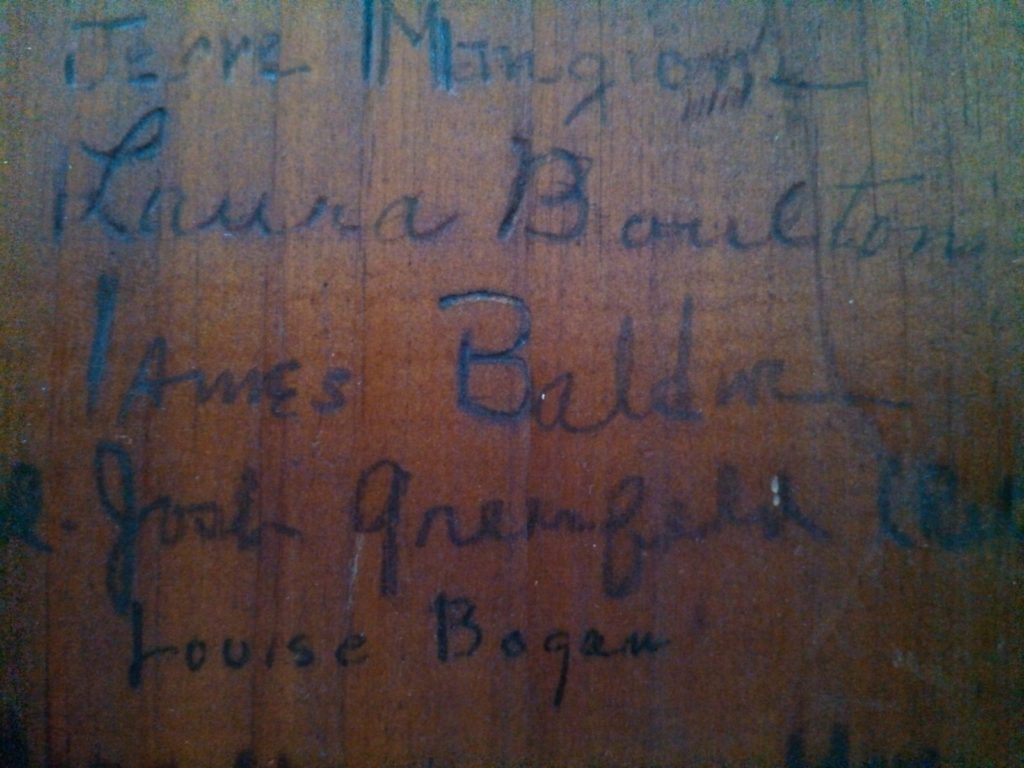

The legacy really is about honoring what it is to be an artist. Our world has been influenced and changed by creative souls who have taken huge risks to make stories without knowing if anybody would receive them. I find it so amazingly moving that James Baldwin is being rediscovered in the way James Baldwin wasn’t fully appreciated 50 years ago. When I was a little queer boy reading Giovanni’s Room under the covers at night, that was major. To be at an organization where he wrote it; that legacy is really personal to me. Everyone needs and deserves that kind of creative space in their life. The reason I can even get up in the morning in these terrible times is that every day I imagine we’re doing something to create time and space for artists. Something that will impact us, move us, create catharsis, and push the needle a little bit. That’s the legacy.

(*Note: throughout this conversation, Himberg would express being comfortable with being referred to as “gay” or “queer.” For the majority of his life, he has called himself “gay,” therefore both terms are used interchanably thoughout our exchange).

Lisa Ahima (Loyola ’21) is a New Orleans-based writer and senior at Loyola University New Orleans. Hopefully you’ll see her short stories floating around on the web sometime.