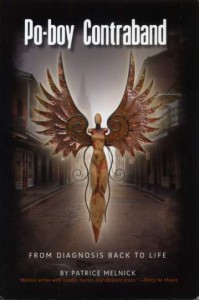

Po-boy Contraband: From Diagnosis Back to Life, by Patrice Melnick. Catalyst Book Press, 2012. $16, 150 pages.

Two points strike me as I read Patrice Melnick’s frank memoir, Po-boy Contraband, about her contraction of HIV when she was in her twenties; first, the relative invisibility and shame surrounding the disease, which is comparable to the shame surrounding Hansen’s Disease (i.e., leprosy); and second, the personal space that seems to be relinquished by the admission of having the disease. The latter is explored several times in interactions with male doctors who seem to feel that an admission of being HIV positive gives them a right to question and ascertain how this woman, the narrator, contracted this disease.

The book is a collection of short tales describing her work in Africa and her initial reactions to finding out that she was HIV-positive; it is also a collection of lists, exams, and literal fun houses of language that illustrate the life and laughter that is not extinguished simply because one is diagnosed as having a disease. For instance, Melnick talks at length about desire, about the search for love and affection; she even makes a comic test for men she might consider as partners, with a list of tasks they have to perform in under 24 hours—including “fixing a toilet” and “putting on a condom” (77). Even in the midst of the comic, Melnick is always present in who she is as a person with HIV.

One chapter, “The Opthamalogist,” gives a harrowing description of a doctor’s repeated insistence on hearing how exactly the narrator contracted HIV—even though that information is irrelevant to getting an eye exam. In another part, when describing the doctor who revealed to her the diagnosis of HIV-positive, Melnick suggests that his inquiries concerning whether or not she had unprotected sex are less medically pertinent and more morally quizzing. AIDS and a diagnosis of being HIV-positive seem to reiterate earlier pathologies in terms of fear, myth, and segregation in relation to the people who are diagnosed.

Most perceptively, Melnick addresses stigma. She observes that white men seem to have a harder time accepting her as a person with HIV than people of color have. She tells the story of an African American student who is harassed by the police, a common encounter for people of color, and makes the jump that race might actually account for why her male friends of color seem less judgmental about her status. She suggests that to be stigmatized and marginalized might actually engender empathy in a way that is denied to people privileged by either race or health.

Melnick continually reminds readers that HIV has shaped her life, but it has not changed it so irreparably that she cannot live. That’s the most important lesson that this book offers: whether it’s learning to Zydeco dance or trying to have a relationship, Melnick is ultimately a person who lives with HIV, not an HIV-positive person just trying to live.

Melnick notes near the end of the book: “I have written a book about what does not happen” (142). I think what she means is that these are merely snapshots of what it means to be HIV-positive—and even then, each is just one experience amid a world of others. She writes that the world is like a stage where the musicians come and go as the set ends, but for the dancers: “Those dancers out there on the floor are not thinking about the end of the set; their lives are normal, but all of our lives are normal and mortal” (143). In other words, different roles determine different acts, all normal in their own right. But what a powerful and binding thought: “all of our lives are normal and mortal.”