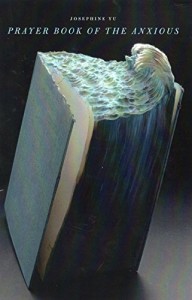

Prayer Book of the Anxious, by Josephine Yu, Elixir Press, 2016. 96 pp, $17.

In the middle of Josephine Yu’s Prayer Book of the Anxious, the speaker in “Prayer to Saint Joseph: For the Restless” pleads for this patron saint not to lead us away “when unease thickens like lime calcifying // in the porcelain basins of our chests.” By the end of the poem, the speaker notes a friend who “stepped off a bridge, holding hands with his loneliness.” The unease has compounded into intolerable pain. Within this range, Yu situates one of her main tropes in this book: the struggles with what pains us, what keeps us alive.

The speaker concludes: “Still our hands as we pack. Remind us the roughest fabric / of the self will end up folded like a sweater / in the suitcase, pilled and raveled and transcendent.” Without “of the self” and “transcendent,” this passage dwells in plain observation. The plain-spoken speaker folds and orders the roughest and pilled fabric one has worn. All is safe and packed away. It seems the self is put away for later use, protected from the turmoil of one’s life. One escapes the pain. Is this escape temporary or permanent? What are the consequences?

The last word “transcendent,” so unexpected, lifts the poem and carries with it the earlier “of the self,” expanding physical details into the abstract, into some sort of comfort transcending the self and the self’s continuum of pain in this poem. In essence, the presence of self ruptures this scene to life. If plain language is a body, then these words that rupture it make it more alive.

Throughout the three sections of this book, the speakers and characters navigate through undercurrents of emotional pain, which mostly involves female experiences and perspectives. Yu frames knowledge and expression of this pain by weaving in “Palm-Leaf Manuscript” poems—prose poems except for the last one. Each of these poem’s titles contains either “myth,” “fairytale,” “fable,” “proverb” (religious), “physics” (scientific), “definition,” or “theory.” Each term invokes a different way of knowing, from a more ancient to a more modern foundation of transmitting knowledge.

The poems in this book inhabit individual quirks, sad circumstances, and failures in a social sphere, all of which seem to contribute to loneliness, yet at the same time the speakers attempt to compensate for this disconnected state. In the first poem, “The Compulsive Liar Apologizes to Her Therapist for Certain Fabrications and Omissions,” the speaker derives a sort of inner strength from being in control of this pain, even before words express it:

a gold tooth hidden in the back of my mouth

near the beginning of words, like a secret

or a blunt pain I could prod with my tongue

a pain I could test and be sure of.

Some speakers in the first section (“Apologia”) are drawn into discomfort, as in “Narcissist Revises Tidal Theory”: “The October coast is not where one turns for comfort, yet / I’m drawn again to this abandoned stretch of rock and spray.” This phrase “rock and spray” metaphorically echoes throughout the collection: that of solid rock, a tangible and definite body, and that of amorphous spraying, the intangible and indefinite movement of emotional tumult.

Yu’s speakers also turn to more “familiar discomfort.” The speaker in “The Failed Revolutionaries Apologize to Their Foreign Sponsors” turns to pillows, where this isolation is further expanded in a broader social context:

However, I’d be lying if I said we aren’t somewhat relieved

and looking forward to the familiar discomfort

of our pallets, the dream of the promised mattresses

with European pillow tops dissipating as we exhale

the usual ration of air, barely a cupped handful.

The speaker employs strong phrasing (e.g. “usual ration of air”) and a language that has precise, confident, and alive diction. These kinds of poetic skills occur throughout this gorgeous first collection.

Besides this apology poem, there’s occasional social critique in later sections, too, such as “Middle Class Song” (second section) and to a lesser extent “An Increase in the Cost of Living” (third section). These poems critique—sometimes humorously—American society of the more well-off and briefly rupture the inner turmoil of speakers with a mostly materialistic focus. It’s a nice break in this book and adds some depth through its variance and through its suggestion that particular social constructions encourage this loneliness and separation. I wish there were slightly more of these poetic moments.

In the second section (“Canticles, Maybe), the poems issue calls for help. There are poems situated as prayer, song, plea, and psalm, in which the speakers and characters—especially female—overcome obstacles or threats, as in “The Thing You Might Not Understand” where the speaker delicately refuses the sexual advance of “the man whose children I babysat in college.” These poems are powerful in their energy and directness. When the speaker asks of her daughter in “If I Raise My Daughter Catholic,” “Will she make a confessional of every space / she enters — … — / lips parted to issue an ecstasy of failings?” one wonders if Yu is asking that question of herself. The book, though, does not quite locate itself in that confessional space and not quite in an “ecstasy of failings.” Rather, it seems to spray in and out of these ranges, playing off of the rock of narrative.

The last section (“Rustle of Offerings”), which seems to contain more personal, plainer language, veers more into the redemptive power of love. In “How Do You Say,”

Everyone I know is thinking of falling in love

or falling out of love, either way with both feet on the edge

like the concrete lip of the deep end

and shimmering before them, the cold, drowning water

of adoration or the cold, drowning water of loneliness,

and everyone is referring to the language of love,

While love is thought and talked about—it surrounds the speaker—it is drowned out in the poles of received (feminine?) social attention: adoration (too much) and loneliness (too little). The speaker is like rock (concrete lip) and subject to spray—love is literally in the air as everyone gives lip service to it.

Yu’s speakers don’t give up a movement toward love, as in the explicit plea “Grant us your patience” in “Prayer to Saint John the Dwarf: Against Giving Up” to the more sublime moment in “Why I did Not Proceed with the Divorce” where in one of the more poignant moments in this collection, and one of the plainest, as if to strip away any pretense of language or image, the speaker concludes:

But mostly, because I slept in the guestroom

for six months

and you tapped on the door

each night, offering a glass of water.

Such a simple offering offers a consolation—as a gesture of love—to loneliness. The language is unadorned, stripped, and at its essence bare.

While the grace of love, and this connection, comes at that simple offering of a glass of water, the self’s enactment of love comes in the final two palm-leaf poems. In “A Definition from the Palm-Leaf Manuscript” the speaker’s “scroll of eventual reckoning” contains the text, “curled on the sofa, weeping inconsolably.” After driving back home and “screaming at deaf mile markers,” the speaker feels the inconsolable pain of presumably a lost love. The elders, though, don’t see the inconsolable. It’s a sacred act towards the self in writing down the word “inconsolably.” In their wisdom the elders “note the word means consolation was offered.” They focus on this offering, not the effect or the rejection implied by the word. The very act of writing down “inconsolably” offers consolation.

In the last palm-leaf poem, “A Theory on the Missing Leaves of the Palm Leaf Manuscript,” which Yu manages into poetic lines (not prose), the speaker asks, “What was recorded that couldn’t be born?” and employs an effective pun on born (as in created and new) and borne (as in carried through, as in the past and an older use of the word). Since there are leaves (pages) loose and missing, what’s recorded (i.e., memory) is transient and at times unreliable.

“The elders won’t say / but remind me some words / throb on the page like nerves when flesh is flayed to bone.” By themselves, these lines risk bordering on the melodramatic. Yu, though, diminishes its drama by placing it as part of her leaf manuscript. She can speak anciently of elders and describe physically this painstaking process of putting together physical word connections, which perhaps counteract a disconnected loneliness. Just as Hester Prynne and her scarlet A, perhaps Yu’s speaker is saying, Here I am—this is me, my pain. I am alive. In this acknowledgement in this book with beautiful, vibrant language, she transcends this personal pain of loneliness and disconnectedness. Here, the gold tooth of the compulsive liar reveals itself in truth, and the rock and spray are conjoined. Here, the words become alive.

Robert Manaster’s poetry and co-translations have appeared in numerous journals including Rosebud, Birmingham Poetry Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, Image, and Spillway. He’s also published poetry book reviews in such publications as Rattle, Jacket2, The Los Angeles Review, Borderlands: Texas Poetry Review, and Rain Taxi.