When we lived in the attic we were make-believe. We lived off Big Fizz Cola, cans of Spaghetti-O’s, and apples. We used the payphone at the deli and washed our underwear in the sink with dish soap. Sometimes I worked temp jobs. Sometimes he worked at his mother’s office. Other times, I worked on movies in New York City, what I really wanted to be doing. But mostly, we slept until the afternoon and hid out in our two-room apartment. We lived in a neighborhood lined with trees and single family houses, fifteen miles west from the city. The Jersey suburbs. But we were the only attic dwellers on the block.

One night, early in December, we were watching Wheel of Fortune, hoping someone would finally win the new $100,000 bonus round. We watched a lot of game shows then, or maybe there were just a lot of game shows on television in 2001. It was a pleasant thing to see people win prizes, become millionaires, but the picture started to roll and no configuration of foil could fix it. When the towers fell that September, the broadcast antenna on top of the north tower went down. As a result, our rabbit ears needed constant adjustment and aluminum foil extensions to get reception and even still, depending on the weather, the time of day, our positions in the room, the picture was often too scrambled to see.

We gave up watching and went out for a night walk. It was cold. I had no gloves. Charlie asked, “Have you ever had your heart broken?”

I practiced my French. “Pourquoi?”

“Do you think people really die of heartbreak?” I didn’t know. “We should break each other’s hearts.” He smiled. “So we know what love feels like.” When we weren’t watching game shows, we were watching Truffaut movies, pretending to be French. “Do you think you’re alive?”

Since college, Charlie had always been that armchair philosopher. He’d get high and muse about life’s curiosities. The night we first met, he studied my palm and told me I was holding a little universe. Admittedly, I fell for it. I loved The Doors and taking ecstasy and he looked a little like a black Jim Morrison with glasses. He wrote poetry. He always knew where there was a rave. And, I mean, that’s a comforting thought to have a whole universe safe inside your hand.

Lately though, his pontificating was getting on my nerves. I needed real facts. “Yes, I’m alive,” I said. “Please don’t ask me how I know.”

“I won’t, but, just so we’re clear, I mean really alive. Are you living, Catherine?”

I threw my arms around his neck and told him to crack my back. He tried, but nothing gave. We walked all night. At dawn, frozen and tired, we returned to the attic, made love under the covers, and listened to the quiet morning—the swooshing of distant cars, wind chimes, water running through the pipes of the house.

Below, we heard Jerry and Audra, the retired couple we rented from, just starting their day as we were ending ours. One of them coughed, the other flushed the toilet. Audra yelled, “Jesus Christ!” And Jerry yelled back, “What do you want from me? Don’t eat it then!”

I rested my hand on the soft place where Charlie’s body narrowed, just before the bone of his hip. “What if they’re us down there?” he asked.

“Us in forty years?” I played along.

“No, now,” he said. “What if downstairs is a universe where we’re seventy or whatever?”

“Well, which universe is real?”

“Probably theirs.”

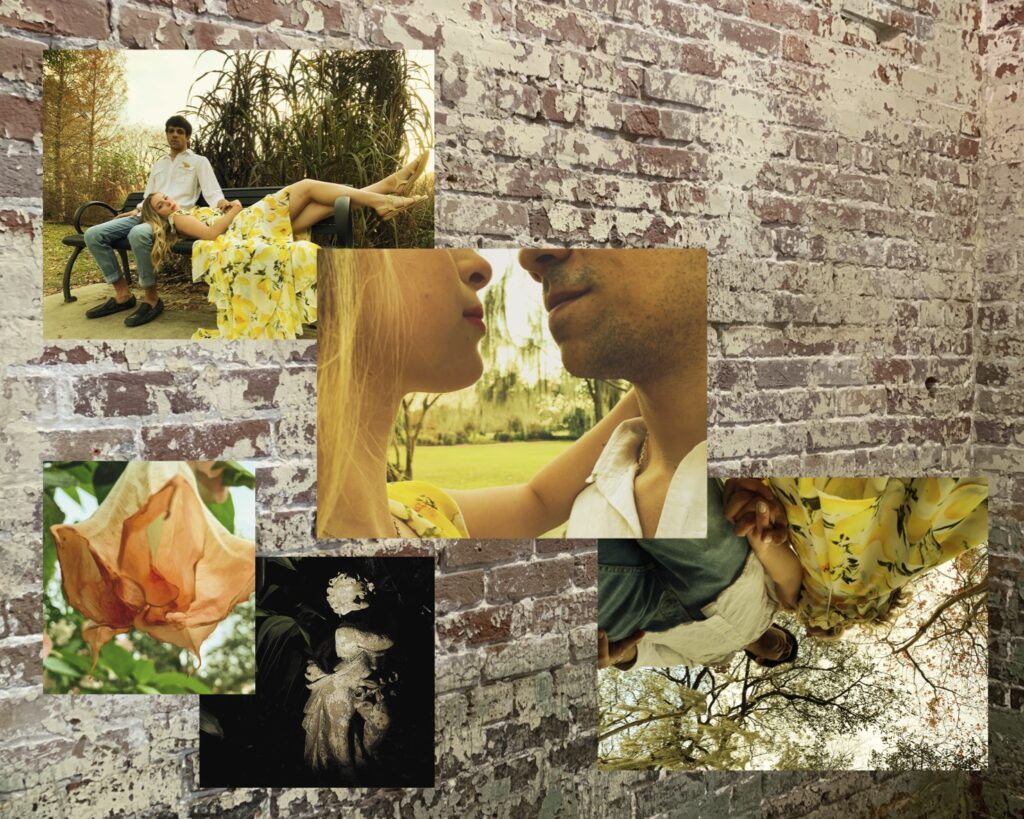

That was disappointing. Jerry didn’t seem to give a shit about much of anything except televised sports, and Audra just yelled all day, her voice like steel wool. They weren’t quite real to me, and I felt mostly real. I laced my fingers between Charlie’s, taking note of our bodies. Our arms, side-by-side like branches, his a strong, tawny bough, mine, a pale stem, newly sprouted, confirmed we were, in fact, real.

I woke just before noon in a panic. I’d forgotten I was working. I hadn’t worked for at least two months, not since the end of October, since my job on an indie film about a dying man throwing himself a suicide party. And since September 11th, I was increasingly afraid to drive through the Lincoln Tunnel into the city, afraid to pass the armored cars, the tanks, the anonymous white box trucks pulled to the side of the entrance for inspection, the men holding machine guns. Now, I just couldn’t do it. I had a gig temping close to home at a pharmaceutical company. I was one of eight people stuffing envelopes. The day before, I was in charge of sealing the envelopes with a sponge dipped in water.

Charlie rolled over in bed, squinted without his glasses, and asked where I was going as I was getting dressed. “Work,” I said, as if he should also think about getting a job.

The office park was decorated for the holidays. Tire-sized wreaths, swaths of red ribbon. I felt hollow, homesick. I wondered what my sister was doing, where my mom was, if they were wondering about me.

Angela, another temp who was working the same assignment, was outside smoking. “You’re here!” She had dyed-red hair with short bangs and she seemed happy to see me.

“Car trouble,” I told her.

“Yeah, whatever. I’m glad you’re here.” Angela started talking to me on the first day of like we were old friends, like we were in it together and it didn’t matter that we had this shitty job of stuffing envelopes. I thought maybe we really could be friends. I wanted to ask for her phone number, but I didn’t have one to give her in return. Friendship used to be easy.

At three, a manager told us that was all they’d be needing us for. I was thrilled the job was over, but the others were pissed. It was supposed to be a six-week job into the new year. We had only put in a week and a half. As we left, Angela said, “See ya!” I said the same, though I knew I just wouldn’t.

As I came in the front door, Audra stepped out of their apartment and offered me a plastic grocery bag. “I thought you two could use these things.” She opened the bag. “Some little oranges that are too sweet, a few boxes of rice, cranberry juice. Could you use these things?” I noticed her fingernails were painted blue.

I smiled. “Thank you.”

“Yeah, well, the juice is open.” Audra was awkward in her kindness. She fluffed up the sides of her fading yellow hair. “You’re coming from work?” she asked. “What do you do?” She scanned me, head to toe, trying to guess.

“Nothing,” I said. “I mean, it’s nothing exciting.”

“It doesn’t have to be thrilling,” she said. “Just make sure it matters.”

“I don’t think it does.” I headed upstairs, wondering what she and Jerry must think about us, the poor kids who lived in their attic. She was still standing at the bottom of the stairs like she wanted want to talk more, but I had to get away before she mentioned the overdue rent.

Since my job was over, Charlie and I were French again. The next afternoon we woke up and started reading Suivez La Piste, a detective thriller I never read in high school, but kept just in case. I lit a cigarette and blew smoke out the window at the maple tree, nearly barren, its few leaves rusted and old. I asked Charlie how long ago it was that the leaves were green. Très French New Wave. He said something about how marking the passage of time was irrelevant and impossible, and I told him he was impossible.

He put some John Coltrane on and made coffee. I watched Audra pull into the driveway in their teal-colored minivan. She emerged from the driver’s seat bundled in her hot pink parka and worked her way across the lawn, loaded with shopping bags and a long cigarette between her teeth. She went inside and yelled about the lines at the store and yelled for Jerry to help with the goddamn bags.

After hearing them go in and out a few times, letting the storm door slam, the glass panes rattle, our door buzzed and we knew it was about the rent. Jerry stood at the bottom of the stairs wearing what he always wore: shorts, a green fleece, white knee socks and sneakers. His thick white hair was mussed on one side, as if he’d been sleeping. “Hi, Catherine.” He’d had a minor stroke the year before we moved in and it still took him a while to get words out. I promised him the rent at the end of the week.

For dinner, we had rice and cranberry juice. Charlie got a fresh piece of foil and we watched The Amazing Race. The night was clear and we got to watch the show all the way to the end without static.

At the end of the week, I went to get my paycheck at the temp agency. The woman there asked, “Are you looking for something else right now?” Even though my check wasn’t enough to cover the rent, I told her I had everything I needed.

“Do you have a job? We have a few temp to permanent situations available.”

I thought of myself in a permanent situation and said, “No, thank you.”

After depositing my check, I knocked on Jerry and Audra’s door. Jerry shouted for me to come in, and I found him sitting on the sofa in his fleece and shorts, a tall glass of brown liquid sweating onto a T.V. tray beside him, a basketball game on television, the volume high.

I had never been inside their house. It was stale and stuffed with memorabilia, knickknacks, stacks of newspapers. An army of beauty supplies lined the credenza, a makeshift vanity, family photos shoved aside to make room; the only photo visible was a black-and-white picture of a beauty queen. A mirror hung above it all next to an odd painting of two ducks.

“She painted that.” Jerry nodded to the painting. “Supposed to be us.” One duck was in the pond, swimming, content. The other was on the bank with a vacant expression. “Coin-coin!” was scrawled in thick, black paint by its beak. “Why it says coin-coin, I haven’t the foggiest.”

“It’s French,” I said, “for quack-quack.”

“Yes,” he said. “I knew that once.”

“Goddamit! Would you look at this?” Audra yelled from the back of the house, her voice pitted like gravel.

“Here.” I handed Jerry a check I knew would bounce.

“I’ll get to the bank tomorrow,” he said. “That’ll be O.K.?”

“Sure. Fine.” It would be the third check I bounced that year.

He folded it and stuffed it in his fleece pocket.

“Jerry!” Audra came in, waving a piece of mail. “Jerry, what does this say? I can’t understand what the hell it says!”

Jerry snatched the letter and she noticed me. “Everything O.K. up there?” She turned on a smile not unlike the beauty queen on the credenza. “Hey, come here a minute,” she said, leading me into the kitchen. “Sit,” she instructed. “I don’t know what size you are, but I can’t wear these anymore.” Audra handed me a grocery bag of shoes. Some of them had never been worn, still stuffed with tissue paper. They were cute. “Do you want coffee?”

I heard Charlie upstairs, the ceiling squeaked, and I said I should go, but she insisted and poured me a cup from the percolator. I was glad. “Jerry! Coffee?”

“What!?”

“Coffee?!”

“I can’t hear you?!”

“Turn the goddamn T.V. down!” she shouted. “All day long with the ESPN.” She smiled and brought our coffee to the table. Sunlight streamed in through the window, the same sunlight that was coming into our kitchen. She asked all about my job. I told her it was temporary and I had no idea what I was doing. “Maybe I should go back to working in film. I went to school for it.”

“You should,” she said. “A smart, young woman like yourself. There’s a lot of inequality in the entertainment industry, right?”

I remembered a producer of a zombie film I worked on who told me I was cute and smart, but if I wanted to get ahead, I’d need to drop a few pounds. “I guess there is.”

“You can make a difference. Don’t ever let anyone tell you that you can’t.” Her confidence in me was uncomfortable. “Let’s have a snack.” She took out a Tupperware and served two bowls of what seemed like sliced apples and mayonnaise. “Waldorf salad,” she said and I wanted to cry because it was so weird and actually delicious.

Jerry sauntered in and kissed her on top of her head. She smiled and he moved around the kitchen preparing to go out back and grill frozen hamburger patties.

“Would you like one?” Jerry asked me.

“Jerry, she’s not going to eat that processed shit!”

I heard Charlie again, a couple thuds from upstairs. “Oh, no thank you. I can’t.” Even though I really wanted to. I wanted to keep sitting at that table with our coffee and Waldorf salad, maybe ask Audra about getting out a stain from my favorite shirt, maybe tell Jerry about a peculiar clanging my car was making, but I didn’t belong down there.

Charlie was waiting for me. “What took you so long?”

I showed him my bag of shoes.

“Weird,” he said. I agreed and looked around our place, at the stacks of magazines and books, video tapes, pictures of friends we hadn’t seen in years, piles of laundry, too much like their house downstairs. “What was it like down there?”

“It was like a grandparent’s house.” We smoked a bowl and watched Breathless. Charlie learned to say Are you afraid of getting old, in French, and I replied, Je suis. We made love on the couch, twisted our naked selves together. One thing I knew was that I loved Charlie. From downstairs we heard bottles and cans clattering, clinking on the floor—the recyclables can tipped over, probably.

“Do you still think this is their universe?” I asked.

“Well, what proof do we have otherwise?”

“Us?” Charlie kissed my hand, got off the couch, and made the proper adjustments to watch Family Feud.

“I might have a job,” he said, “selling furniture slipcovers.”

“You might?” I went to the window to smoke a cigarette.

“They’re stain-resistant and wrinkle-free.”

“Is that what you want to do?”

“They’re made of space-age polymers.”

“Aren’t we in the space age?” I asked.

“I guess we’re not quite yet. Why else would that be a selling point? What do you think?”

“Well, if it’s something that matters to you, then you should.” I exhaled smoke and saw that the maple had finally lost all of its leaves. It was lifeless and brittle, now, like it could break. One day, it would bud again, and I understood what it meant to be dormant. It was a hopeful thing.

The day ended like it had given up. It was not even five o’clock and our apartment, lit by only the television, was dark. I flipped all the lights on and Charlie turned the television off. I looked through the weekly film and television job list that I printed at the library, circled a few listings, and turned on our computer to write cover letters. As the desktop was loading, Audra started yelling again. “Turn that goddamn television down!”

I couldn’t disagree. Even we could hear the referee whistles and the squawking sneakers all the way upstairs.

The CD that was stuck in our computer came on after it booted up. Charlie whooped as he always did when the bass line started. It was a deep-cut-trance mix Charlie ripped from his college roommate. He started making rice, moving to music, dancing with measuring spoons and the carton of milk, a kitchen rave. It embarrassed me to think about my hair in pigtails, wearing a candy necklace and a pair of extra wide-legged jeans, my pockets stuffed with Chapstick and gum, dancing until breakfast and bursting out of some warehouse into the mid-morning somehow changed.

“Are you listening to me?” Audra shouted. “You’re not deaf. Are you?! Jerry!”

“Jesus,” Charlie said. “Why can’t she just give up?”

Jerry was quiet. Maybe he had given up. “I think that’s just how they communicate,” I said.

I saved my cover letters to a disk. I would print them at the library and fax them from the stationery store. I’d have to get a new calling card to check in with my mom to see if anyone had called for me. I thought about being on a film set. The chills I’d get when the camera was rolling. But then I envisioned driving into the city, my car inside the amber-lit tunnel, a rumbling, a movement, a fireball hurtling through the cement passageway, crumbling concrete, torrents of river water bursting through the walls.

I shut down the computer and with it the music and the uneasy feeling of anticipation it gave me. I thought about taking a walk in the night, but I had no gloves, so we watched television, adjusting the foil several times until we finally tuned in the picture. But it was a cloudy night, or maybe we were sitting in the wrong spots on the couch and by midnight we’d weaved a web of foil clear to the ceiling and across the hallway, held up with thumbtacks.

That’s when Audra started hollering for Jerry as if he were lost. “Jerry!” There was urgency. I could feel it. Jerry did not holler back. I imagined him on the couch, stoic as a monk, steadfast in his resolve of silence and basketball. But even their television was silent, now.

“Jerry!” Audra yelled, nearly growling.

It was almost too much to bear and I tried to ignore her, but the T.V. picture rolled again and scrambled, and I pulled the foil web down and tried to just point the rabbit ears to the right spot. “These fucking things don’t work.” I pushed them off the top of the television.

“Want to just watch a tape?”

“If I’m ever screaming for you, please answer me, O.K.?”

A heartbeat later, we heard the siren and went to the window. A police car parked in front of the house. We heard them pounding on the door downstairs and another siren. The ambulance arrived and we waited at the window. A stretcher went in and came back out with Jerry strapped to it, a bag of air being pushed into his mouth, Audra trailed behind clutching her pink coat. The ambulance took off into the night.

The apartment felt empty, a hollowness below us so vast it could have sucked into the void. My little sister often thought the world was ending. She’d always ask if I wanted to stay awake with her to see it go. I never did. She’d warn me that we’d all be gone by the next morning. We all always remained. I remember calling her two years ago on New Year’s Eve. I was drunk and thought Y2K was a joke and I wanted to know what she thought. She hung up on me. But now, I wanted to tell her what it felt like to wake that morning in September, to see it happening on television, to then walk outside and join our neighbors at the top of the hill to bear witness to the plumes of smoke climbing into that thick, painted blue morning sky, as we stood in the absolute silence of our street. I wanted to ask her if she knew the night before that the world might end, but we weren’t close like that.

I slept holding on to Charlie and in the morning, our door buzzer woke us early. I opened our door to find Audra at the foot of the stairs. “Hello?”

“Well, he’s gone.” Audra crinkled a clear plastic bag in her hands, Jerry’s sneakers and green fleece stuffed inside. Was my check still in there? “Another stroke. The big one. He was the love of my life.” Audra went into her apartment, leaving the front door open. Clear morning sun spilled into the hall. It was frigid. I went down to close the door and saw the lawn covered in white frost, glittering.

Charlie was at the top of the stairs. I pressed into him, trying to hide from the morning, from all the awful things that happen on beautiful mornings. Was it only just today Audra realized Jerry was the love of her life or had she always known? I had no idea what love meant, and I wished I’d had French words to describe it all. Charlie rested his head on mine. “Crack my back,” I said, and he pulled my arms around his neck, lifted me off the ground and my spine popped like firecrackers.

Apryl Lee is the co-founder and host of Halfway There, a literary reading series in Montclair, NJ. Her short stories and essays have been published at Joyland Magazine, Word Riot, Underwater New York, Keyhole Press, Necessary Fiction, and Handwritten Work, among others. She teaches screenwriting at Seton Hall University and for Montclair Film. She holds an MFA from Sarah Lawrence College and lives in New Jersey with her husband and son. She has recently completed a novel-in-stories.