{From Press Street’s Room 220}

Like any historical novel—even one set in recent history—Rachel Kushner’s The Flamethrowers is a convergence of the past and the present, the time before now rendered with the help of research but intrinsically influenced by the contemporary moment that shapes the author’s daily life. And like many novels, The Flamethrowers is an amalgam of the author’s personal interests strung together by her character’s movements—in this case, the downtown New York art scene in the late 1970s and the Movement of ’77, a leftist revolt that rocked Italy that year. Kushner’s work as an art critic—she’s written for Artforum for more than a decade—helped spawn her interest in the former, and as she researched the latter after learning about the Autonomists and other components of the Movement of ’77, the texts of that era came alive as the Occupy and other movements culled them for instruction and inspiration for their own political actions.

The thread that connects these two elements—New York art and Italian revolt—in The Flamethrowers is Reno, a recent art school graduate from Nevada who moves to New York to cut her teeth as an artist and adult. She wends her way into the world she desires and becomes involved with Sandro Valera, a prominent minimalist who’s also the estranged scion of an Italian motorcycle baron—which is fortuitous, considering Reno’s transfixion with both art and motorcycle racing. The plot unfurls from here, with wild forays that entwine the narrator and others that transport the reader further back in time, to the genesis of the Valera empire, and into the depths of the imaginations of characters Reno encounters, who hold forth with indeterminably fantastical stories and revolutionary theories.

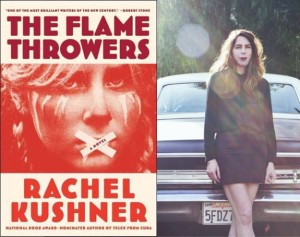

Rachel Kushner is also the author of Telex From Cuba, which was a finalist for the 2008 National Book Award. She will present The Flamethrowers at a Happy Hour Salon hosted byRoom 220 that will also feature readings by Nathaniel Rich and Zachary Lazar from 6 – 9 p.m. on Thursday, May 9, at the Press Street HQ (3718 St. Claude Ave.). As usual, complimentary libations will be on hand, though we strongly suggest donations. Copies ofThe Flamethrowers and titles by Rich and Lazar will be on sale courtesy of Maple Street Book Shop. This event is free and open to the public.

Room 220: You wrote a piece for the Paris Review in which you mentioned writing about mass demonstrations in The Flamethrowers while Occupy Wall Street was on the news. While you were writing about riots, they were erupting in London and Greece. In depicting the political elements of the book, how much was your eye turned toward the present and what was going on?

Rachel Kushner: The way I conceive of the novel—my experience of writing one—is of living in a world that is constantly being shaped and filtered by the book I am writing. My eye is always turned toward the present, because the present, the whole extended plane of life, is arranging itself to be lifted up and transported into fiction. I thought a great deal about these past events in the 70s. I had encountered the Autonomist movement through my husband, who writes about French and Italian philosophy and political theory in the 20th century, and through him I met some Italians who knew a great deal about this milieu. I thought it would be a pretty thrilling context for a novel.

As I was writing the book, Autonomia and the Movement of 77 started to seem like something of a cultural zeitgeist. A lot of people were interested in Italy, and that’s partly because of Occupy and other movements that were going on. Even people in the Arab movements were looking to Italy, and people in the anti-austerity movements across Europe. It’s a really interesting time that hasn’t completely been studied and declared defunct in the way that May ’68 has. The Italian 1970s may have more interesting and relevant links to the contemporary era, given that the autonomist actions extended beyond the factory into the cities and were a set of refusals that no longer cohered with the factory and a traditionally Marxist class composition. Beyond the complicated issue of Autonomia, there were these rather simple coherences between what I wrote and what was going on in real life. As I wrote about the blackout in 1977, looting was erupting in London. As I wrote about people being tear-gassed in the streets of Rome that same year, people were being tear-gassed in Oakland. As I wrote about an anarchist street gang engaged in full-on combat with police, I watched live feeds from Greece of these kids fighting the cops in insanely asymmetrical battles, launching molotovs with lacrosse sticks.

I knew a lot of people involved in Occupy—many who are younger than I am, people in their early 20s for whom Occupy will probably have been the essential historical event of their time. My friends in Occupy are and were all interested in Autonomia, and they were reading the same texts I was reading. I did a reading from the novel-in-progress in L.A. and everyone thought that what I was reading was about them, when it was actually about this historical group of anarchists in New York City from ’67 – ’71 who were called the Motherfuckers. People know about that group, but my friends sort of thought I was writing a text that was related to them or inspired by them, and in a way they were correct.

Rm220: Factory workers play a potent role in the political landscape of your novel, as they have in real political movements throughout recent history. In terms of writing as part of a contemporary conversation, how did you view that specific element, especially considering the decline of organized labor in the United States?

RK: The 70s in Italy is a pretty complicated milieu, but it’s something like this: A lot of the theoretical components of Autonomia were born in the factories of the highly industrialized north of Italy—there’s the Pirelli factory where the Red Brigades famously got their start, and there’s these motorcycle factories, and of course there’s Fiat. But none of it, as I understand it, was about “organized labor” in a traditional sense—though I should say I’m no expert on autonomist and workerist history. I think some of the theories about why the Hot Autumn of 1969 at the Fiat factories was so intense and so many workers participated in the strikes is that many of the workers come from the south of Italy, which does not have the culture of work that you find in the north. This difference between the south and the north manifested itself in this total disregard on the part of the workers for their labor bosses when these strikes start to happen. They were primarily strikes that were not organized by union leaders, and instead something more like wildcat strikes. The movement partly happened because workers rejected their unions and the communist party altogether. They organized themselves, which is the origin of the term autonomia.

The component of Autonomia that was Rome-based was much more of a sub-proletarian, lumpen population of people who were not productive, and they certainly didn’t do factory work because it’s not an industrialized part of Italy. That’s a really complicated component of things: How did this mass revolt and mass illegality across multiple sectors of people occur if there’s no factory as a site of principle antagonism? People would try to explain it to me: “Well, people in Rome, they are not interested in work, they wanted to have a different kind of life. It’s a total rejection of bourgeois values.” There was simply a refusal to work, and I think that relates to what people are feeling now. Those in Occupy were not making a specific set of demands. They weren’t asking for health benefits and better minimum wages as barristas or whatever. It was, and I hope remains, a kind of rejection and a refusal, rather than a demand for a specific and better-negotiated position in the service economy—which is to say, the economy. I love that moment in when someone asks Marlon Brando what he’s rebelling against and he says, “What do you got?”

Rm220: And how did you come upon the New York art world of the late 1970s as a context in which to set part of the book?

RK: I’m familiar with that era partly from having written about contemporary art—a significant time and an influential time still for contemporary art—and partly from my childhood, and having been exposed, early, to some of it. That period also coincides with the death of the industrial age in the United States. It seems like an interesting coincidence—or not a coincidence—that the artists in SoHo were moving into these former manufacturing warehouses, and even using the detritus of manufacturing itself to make their work. As I was beginning to write The Flamethrowers, there was a retrospective of Gordon Matta-Clark at the Whitney. Later, mid-way through the book, there was a retrospective of the Pictures Generation at the Met. A Jack Goldstein show is opening like next week in New York City, and I just saw it at the Orange County Museum. The 1970s is still an informing era for contemporary artists, who continue to be drawn to it, and to feel a need to contend with the figures and ideas and the discourse of that era. All of this made the era feel worth writing about.

Rm220: The book is filled with people talking over each other, or at least talking not so much to communicate but to simply talk. You have all these monologues—Ronnie’s story at the end, Stanley Kastle’s monolog, which is literally to no one. They’re excellent stories, but their quality doesn’t change their motivation. Relate this to your writing practice. How much of your writing practice is to communicate, to take part in the conversation, and how much is simply to monologue?

RK: I’m not sure there is a clear and clean distinction between “to communicate” and to “monologue.” The person who speaks in a long breathless jag probably feels he is communicating something important or he would not bother. I think a lot of people want to talk more than they want to listen. Meaning some component of their speech is always about the speech itself and their need to perform it and to hear their own voice and to dominate by talking, more than it is about making contact with a listener. But there is some level at which neither monologue nor communication are what matter to the novel, the rules of it, because the author is always communicating to the reader. Nothing is by accident or impulse—it’s all there, ultimately, by some kind of design. The author, ideally, is not a bloviator at the dinner table, but registering the phenomenon of such to have fun or be comic or make some other kind of point, for instance, to introduce textures into the narrative that the narrator can’t, since she is one voice, unmodulated.

For me, this resembles life—sometimes there are these people who are frankly bored when anyone else in the room is talking but them. And I like the sort of self-declared experts that can say a lot more about themselves than they think they’re saying when they want to tell you every detail about a subject of which they have the impression they are an expert—and sometimes they are an expert, but they tell you about their ego’s needs as they inform you.

Reno, the narrator, can’t entirely surf the more sophisticated discourses of the people around her and so she is often more quiet and withdrawn, which lent more space for other people to talk. I was also interested formally in the challenge of letting dialogue take over for very long stretches, letting someone who isn’t the narrator talk for thirty pages. The narrator is there, but she’s simply recording what he’s saying as a listener in the room. While I was working on this book I re-read The Savage Detectives by Bolaño. I love the way he lets people tell stories within stories. He’s obviously not the first person to do that. Conrad does, uses framing mechanisms. I was interested in developing my own manner of doing that.

Rm220: You mentioned Savage Detectives, but I thought several times of 2666 while reading this book—your narrator is perpetually on the outskirts of these things that are going on, which is the same for most of the narrators in 2666. And in 2666, as well, there are lots stories told by characters that go on for pages that, seemingly, have nothing to do with the plot.

RK: I read 2666 when I was just getting the engine of my novel running. For me, that novel and Savage Detectives have somehow become one massive tapestry. I think they are interrelated in a way that Bolaño’s other books are not. His other books relate in certain surface ways or in structural ways, but those two novels seem to be circling around the same questions—of the nature of evil, for instance—one in a more playful way and the other in a more dark and vast but insidious way. I think I’m equally influenced by both of those books. I certainly studied them—as many other writers have—and I’m flattered you thought of 2666.