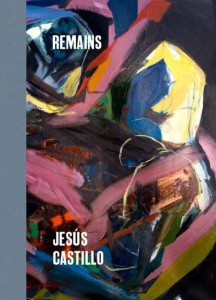

Remains, by Jesùs Castillo. McSweeney’s, 2016. $20, 109 pages.

Jesùs Castillo’s first full-length poetry collection, Remains, is a stark collage of voice, nature, and the breakdown of culture, a world in which “the bombs had fallen with the majesty / of gods shitting.” The poems have a modernist, dystopian feel to them and yet the speaker’s voice remains strong all the way through to the very last page. Castillo puts the solitary voice in conversation with a collective voice which creates endless layers of consciousness and philosophical thought.

Remains is made up of a series of small poems split up into six sections. Each poem reads like a mini journal entry which gives it an intimate quality even though the voices running through this book are so expansive. Each poem is packed with nature images, personal statements, and philosophical musings. Even the most simplistic declarations glow with insight when the speaker proclaims: “Aren’t we all / just doing our jobs?” or “I just want to be left alone sometimes.” Variation also occurs through the use of repetition, caesura, and line fragments. For the reader, these changes are much appreciated as a contrast to the default paragraph-like, narrative style.

The poems in Remains light up the most when the lines hold the strongest rhetorical tension. Castillo has a bounty of rhetorical gifts, so many that it would be impossible to comment on all of them. Castillo’s best moments of skill occur in the sections that differ from the solitary narrative voice:

A hinge turning in a stranger’s life. A friend walking

toward you in a crowded room. A sound like a sketch.

A blank drawn. An awkward moment in conversation.

A letter in the mail. A mode of transport. A set

of excuses. A distance. A pain in your left temple.

A finite dream. A slip of the senses. A closed lid.

A garden fountain. A fear vector. A need

to be addressed. A need for sound. A brown lawn.

A sky littered with faded jet trails.

Here, Castillo presents readers with a list of images. The connections aren’t clear, but instinctually they feel right. This is one of Castillo’s strong suits: he brings order to chaos in this particular section while at the same time interrupting the steady narrative rhythm of the book.

Castillo is also great at playing with surrealistic images. He sprinkles them all through Remains. The most prominent section includes a series of images involving limbs:

Limbs bursting through bolted doors. Limbs marching

through a crowded room. Limbs dancing to the pull

of unhinged minds. Limbs lying. Limbs contracting

in pleasure. Limbs with newspapers. Limbs

at the border between madness and boredom.

Limbs free from thirst. Limbs falling out of broken time

slots. Limbs seated in neat, cushioned rows. Mute

limbs. Limbs moving in tandem with the ground’s

vibrations. Limbs discarded on a Sunday morning. Limbs

meeting silently for dinner.

This section is incredibly successful because it brings in the war-like, dystopian energy that surges beneath the surface of the book. As a reader, there is a feeling that something horribly violent has happened to the modern world, but there are no specific details given. Instead, the reader is presented with morbidly artistic images and is expected to connect the dots. Each poem is a highly-compacted little puzzle without a tangible solution. The challenge of comprehension is worth the mental workout.

Remains could benefit from multiple analyses; Castillo is a renaissance man when it comes to rhetorical variations. He’s a master of contradiction: “To retrain the eye we close it. / To start again we make our way through mounds / of garbage.” Remains is a philosopher’s paradise where musings are so plentiful they are like fruit bursting from trees: “Is it possible to get rid of time by refusing / to make machines?” And this image is hauntingly radical: “If you liked the slow sex of winter, you will / love these dead flags flapping in the sunset.”

Castillo doesn’t just focus on fragmented destruction. A big feature of the book is the way the narrative defiantly moves forward, but it’s about more than just survival skills; it’s an assertion of life that focuses on youth: “Your children are pulling guns on everyone because they / have to…Your children / can be found under the rocket’s light, making love to fight music, / giving each other a thousand new names and taking them off again / gently, like earrings.” Recreation of life is wild and inevitable, even in the most toxic situations. It adds another note of tension to the book:

When the bridges folded, we sought solace in the words

of our past minds, found ways to praise ourselves,

aware we were nonetheless falling apart.

Here the only option is to start

forgetting everything. On the rooftops of the city,

we look up and write the stars down in our tablets,

renaming each of them at whim. Only impulse

can save us…

And yet, Castillo complicates this idea further by introducing a nihilistic god:

And once it was finished, he turned himself

into a small brown cricket, and set himself down

on a patch of grass, to live and die in his creation,

having made himself forget he ever made anything.

This kind of recreation vs. nihilism is what makes Remains so thought-provoking and complex. According to the world Castillo has set up, humanity continually asserts itself in resistance to a god that wants to fade out of existence.

Remains is riveting, best read a little bit at a time. It’s the kind of book that should be savored and mused over, a stimulating read with regard to philosophy and humanistic concerns, full of fragmented, dystopian energy and the promise that there will always be “clearings in the forest only the lost / can find.”

Andrea Syzdek is an MFA candidate at the University of Houston. She has been a Poetry at Round Top fellow. Her poems have been published or are forthcoming at descant, Concho River Review, Iron Horse Literary Review, and South Carolina Review. Her reviews have been published or are forthcoming at Gulf Coast, Kenyon Review Online, New Orleans Review, and elsewhere.