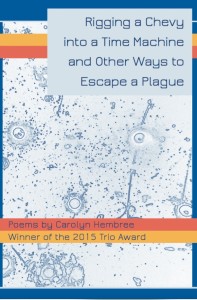

Carolyn Hembree was born in Bristol, Tennessee. Her debut poetry collection, Skinny, came out from Kore Press in 2012. In 2016, Trio House Books published her second collection, Rigging a Chevy into a Time Machine and Other Ways to Escape a Plague, winner of the 2015 Trio Award and the 2015 Rochelle Ratner Memorial Award. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Colorado Review, Contrary, Gulf Coast, Indiana Review, Poetry Daily, and other publications. An assistant professor at the University of New Orleans, Carolyn teaches writing and serves as poetry editor of Bayou Magazine.

INTERVIEWER

Both your first book, Skinny, and this new, powerhouse follow-up, Rigging a Chevy into a Time Machine and Other Ways to Escape a Plague, approach, flirt with, bed but do not wed what is, perhaps, the first hybrid genre: the novel in verse. If Skinny invokes the silent film as an analogy, Chevy reads to me more like a series of tableaux vivants, a narrative that unfolds across a sequence of film stills, as does Chris Marker’s La Jetée. What are these books’ relationships to genre, and what is your own, more broadly, as a writer?

HEMBREE

Backseat head but do not wed more accurately describes my relationship to the verse novel and other traditions; like the liverwort, I favor asexual reproduction. Skinny and Chevy include a cast, narrative arc, and voyage and coming-of-age motifs; however, both collections privilege the individual poem over holistic prosody. My books rub against the KJV Genesis (arguably, one chapter of a verse novel), Native American lore, hill music, ballads, and Shakespeare’s tragedies as much as they do Beowulf, Dante, Milton, or Homer.

“Storytelling is mother tongue, mother’s milk of the American South. I always had the impulse. I just never knew how to tell a proper story,” C.D. Wright said in a 2015 interview for APR. Yes, my people were big on legend: somebody did somebody something; somebody got caught and ousted or took off; somebody stopped or started believing. Teller more than tale mattered, their angle on the subject. Early ballads—anonymous so who knows who started them, we all did—get rejigged when said, sung. How many damn versions of “Bonnie Barbara Allen” can we find in print? Hundreds. Same goes for “Pretty Polly,” a murder ballad recorded by B.F. Shelton on the 1927 Bristol Sessions. Ask anybody with a fiddle and you’re likely to get the same tune but substantially different lyrics; that’s what interests me, the version more than the story. I want to learn the singer’s sympathies.

Yes, I think your tableaux vivants analogy applies to the core narrative poems, the murder ballad of Chevy, as the characters sort of pose in a timely moment; I’d say there’s a piped-in voiceover that accounts for the vernacular. The final sections of the book that complicate the earlier narrative seem less comparable to still pictures.

As for relationship to genre, both books are poetry, more or less. Although Chevy involved documentary research, that approach ultimately got one-upped by the lyric gesture. I abandoned what I wanted it to be for what it had become, a sauce not a stew.

Me, I’m a bard.

INTERVIEWER

I think the way that Ben Marcus talks about plot in his introduction to the Anchor Book of New American Short Stories is fairly wonderful and utterly apropos of Chevy. He outlines plot not only as the action that unfolds in a story, but plot as piece of land, the place of that unfolding, saying that “plot would refer to setting, the space in which a story occurs.” He goes on to explain that by this he means the body as place for this unfolding, and while the ways in which your work “comes to life inside us,” to quote Marcus again, must be left to each of us readers to experience and share ourselves, this points to another important aspect of your writing: place. How does place inform your writing, generally, and Rigging a Chevy into a Time Machine, specifically?

HEMBREE

Where comes first. My sensibility, my intuition, my instinct all drive at place. I recall life events in tableaux vivants, to borrow your term. Even as a young reader, I prioritized the work’s physical setting; “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” I would pull from my parents’ bookshelf; unable to get past the character of the landscape, the bridge, the churchyard graves—oh, that wooden bridge—I’d reread until the features of the textual world were superimposed over our living room, such “fearful pleasure.”

Chevy started with a memory of this yellow honeysuckle I would pass in Bristol en route to grade school, how I would sometimes strip a whole vine for its nectar. Over the twelve years that followed my inciting image, I dwelled on the setting of Appalachia. Research trips to the Blue Ridge Mountains and westward into central Tennessee allowed me to explore the region where my ancestors squatted and, ultimately, put down roots. On one of the trips, I visited my great-great grandmother’s homestead and porch-sat with a lady who remembered her. The place names, too, told their own stories, names like Calfkiller River and Sparta, Tennessee. Taking in the flora and fauna, that was the greatest boon of the explorations. I was grabbing at something huge, knowing I had to.

“Nature is a Haunted House – but Art – a House that tries to be haunted,” Dickinson wrote Higginson. Once I returned to New Orleans, I would outfit my office with notes and photographs, materials from East Tennessee State University’s Archives of Appalachia, and ephemera from the trips. Since I was a kid, I’ve worked inside a marked space, my witchy world. Yet, 99% of what I write and cull gets thrown out: again, the sauce not the stew. No matter, the materials serve to buoy me when I feel incapable of completing a large project. An adage for my process might read, Build it and it will come.

INTERVIEWER

To continue with the Marcus, he goes on to reference the verb form of the word, citing that to plot is to scheme in secret, a schema he relates to form, or style. This plot “suggests mystery, unrevealed conditions driving the characters or language through a story. If a story has a plot in this sense, then, it is what the story is withholding, not what it tells. […] The story, then, is what the story is hiding, and the hide is indeed a piece of skin, whose effect is to conceal the body. How it does this is what we might call style[…].” I think this holds equally true of poetry. How do you see the variety of forms, range of diction, and sometimes antiquated syntax—the style of Chevy—working to bring its poems—and characters—to life for the reader?

HEMBREE

“Unrevealed conditions driving the characters or language through a story”: yes. I often describe poems as feeling lived-in. The lyric poem (in the broadest sense, any non-epic) shorthands explication, yet hosts a multi-dimensional world, one that exists before and after the poem, wherein grammar suggests our “unrevealed conditions”: participles smuggling action, adverbs narrowing the temporal, plural forms generalizing a world, determiners personalizing context, for example. I like to pressure every word.

“Antiquated syntax,” Mr. Edgerton? Why, I never! As you well know, I am twenty-nine and likely to remain so. I prefer the term poetic syntax, and my ornately ragged structures reflect my sensibility; I favor variety over symmetry. When crafting the sentence—craft, that’s a no-no word I’m learning, but it comes from the German strength (strength before skill) so I will say craft—I privilege speech, natural and performed, as I’m interested in the oratorical effect of figures of speech. Even with alternate ordering or elision that contorts the sentence, the final test is speech. So, to pass muster, an utterance must be habitable by one or more of my voices.

Bakhtin’s theory of dialogic language and literature and Dorothea Lasky’s lecture “The Metaphysical I” grant permission to those, like myself, who eschew the concept of a unified voice, those whose work features numerous transmissions. More than theory though, the polyphonic writings of Dickinson, Donne, Shakespeare, Stein, Antonin Artaud, Mina Loy, Etheridge Knight, John Berryman, Thylias Moss, D.A. Powell, C.D. Wright, Harryette Mullen, and Douglas Kearney have taught me to access my voices.

To speak to the range of diction, I’ll go to Wright’s interview again: “I like words period. All tracks of diction. Trashy language, haute language, archaic language, colloquial, idiomatic, specialized.” I was exposed to the books of my educated parents. Through my community and extended family, I was exposed to oral tradition, Appalachian and other Southern dialects, and regionalisms.

Save a couple of loose syllabics, Chevy varies free verse rather than closed forms, including strophic, prose, hybrid prose/verse, and field composition. The news provided by the forebears, the book’s chorus and only true persona, demanded specific poetic kinds: the abecedarian primer, the parable, the fable, and a necrology. The Stephen Hawking question-titled poems of the last section also demanded a particular shape from the outset, a mix of discursive prose and more lyric lines. Such hybridity lets the poem move between, sometimes hover over, song and talk.

A restlessness pushes my pencil—

Michael Tod Edgerton is the author of Vitreous Hide (Lavender Ink, 2013). His poems have appeared previously as the winner of the Boston Review and Five Fingers Review contests, and in Coconut, Denver Quarterly, Drunken Boat, EOAGH, New American Writing, New Orleans Review, Sonora Review, and Word For/Word, among others. He holds an MFA in Literary Arts from Brown University, a PhD in English from the University of Georgia, and teaches creative writing as an assistant professor of English at the University of Central Oklahoma. Check out Tod’s ongoing participatory text and sound project, “What Most Vividly,” at WhatMostVividly.com.