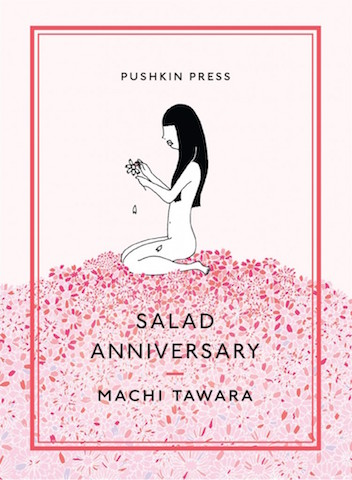

Salad Anniversary, by Machi Tawara. Translated by Juliet Winters Carpenter. Pushkin Press, 2015. $14, 112 pages.

Since the end of World War II, the Western appetite for Japanese literature has grown tremendously, yet most writing being translated from the small archipelago in the North Pacific is of a singular melancholy tone. Haruki Murakami is doleful, Hanya Yanagihara’s crestfallen, Banana Yoshimoto is a near infinite abyss. The poet Machi Tawara is of a different ilk; she has a distinctly sanguine tone. Over eight million copies of her 1987 book Salad Anniversary have sold, and the collection is read by every student in Japan. This May, a new English translation by Juliet Winters Carpenter is available from Pushkin Press.

Salad Anniversary is composed of tanka: short, thirty-one syllables verses. Tanka have been around since the eighteenth-century. After hundreds of years of the same verse structure and repetitive themes, many considered tanka tired and lacking creativity. Tawara brings new life to the form. Loyally integrating perennial themes of weather and nature, she focuses bright and specific moments like the sweet pungency of a frying onion, or celery leaves sticking out of a bike basket.

Tawara is a champion of gratitude and glee, best capturing simple satisfactions:

Sharing the sun with you

summer’s first tomato,

skin firm yet delicate

From the garden to the produce aisle, her verses are full of zest—combining a feeling of contentment with images of ripening fruit. As in the verse above, she creates a sense of intimacy and novelty in sharing “summer’s first tomatoes.” These humble ephemera open into larger world of optimism.

Sweet-sour cherries

on the rooftop terrace—

right now I feel

more loved than anyone

Her vegetable imagery evokes ripe affective moments; however, it is the larger narrative structure of Tawara’s poems that has given the verse form new blush. In the final poem of the collection, “Always American,” Tawara moves from running “down a windy slope,” to “two people in a roadside crowd,” to the “somehow transparent” feeling of being loved in a few pages. The penultimate tanka of the poem is similarly evocative:

Between us the word “good-bye”—

an evening of short questions

and short answers

In Japan, Tawara’s poems have inspired a feature film. Tora-san’s Salad Day Memorial tells the story of Tora-san visiting an ailing acquaintance in Komoro. At the hospital, Tora-san meets a beautiful doctor, with whom he falls in love. A niece records the story of their romance in tanka. Grossing more than a billion yen, it might seem unbelievable that a collection of poems could inspire a blockbuster, yet Tawara’s verses deliver.

Tawara’s tanka bunch together like an overfull vine of grapes, creating powerful narratives that often have a timeless feeling, like that of a folk legend. In “Jazz Concert” (a poem one would imagine Murakami enjoying), Tawara traces the rhythmic vibrations of a jazz concert, its reverberations in a can of beer, to the tingle in her ears the next morning. To overanalyze her poems would be to steal their flavor. It is the weaving together of the part (her hopeful tanka) and the whole (the narrative of her poems) that yield such a fruitful collection, perfect for the coming summer.

Jacob Kiernan is a doctoral student in comparative literature at NYU, and works at Bookforum. He has written for On Verge, MobyLives, and The Jordan Center. He’s currently working on his novel, Empire of Hope.