“I am not entirely opposed to madness, not when it comes with this kind of clarity.”

― Akwaeke Emezi, Freshwater

When I heard New York Times art critic Holland Cotter speak at Tulane several years ago, he said something like, taste is a form of habit, and habit is inherently conservative. Unfortunately, this has not kept me from forming habits of taste. Some of my most stubborn art-viewing habits have to do with how a show is installed or presented, the vibe I find when I am there. I went to Good Children Gallery on the opening day of Gabrielle Ledet’s show, Swam to the Moon, which consisted mostly of pastel portraits on paper, installed salon style. For the duration of my visit, several of my habits of taste were suspended.

I hate noise, which I define as sound that is not part of an intended experience. As soon as I was in the gallery, I was aware of overwhelming noise coming from a video in the back gallery. I said to my friend Adam, “I hope that that video at least belongs to the artist.” It did. It was uncomfortable, but maybe I was supposed to feel uncomfortable.

There was no list of works. I asked the artist–who was still setting up the show–if the works were individually titled, and she said they were not. She said they were made with pastel, oil crayon, and acrylic.

Still feeling disorientated, I moved through the space and looked in to the dark back gallery. There was a projection of a crowded street, filmed in Africa, according to the artist who did not specify where. There were not a lot of people in the space, maybe five besides Adam and me, but it felt crowded. The artist and someone helping her were walking back and forth through the gallery and outside, and voices are always amplified at Good Children. In this atmosphere, I looked at the work that covered the walls, vibrant and uneasy portraits surrounding me.

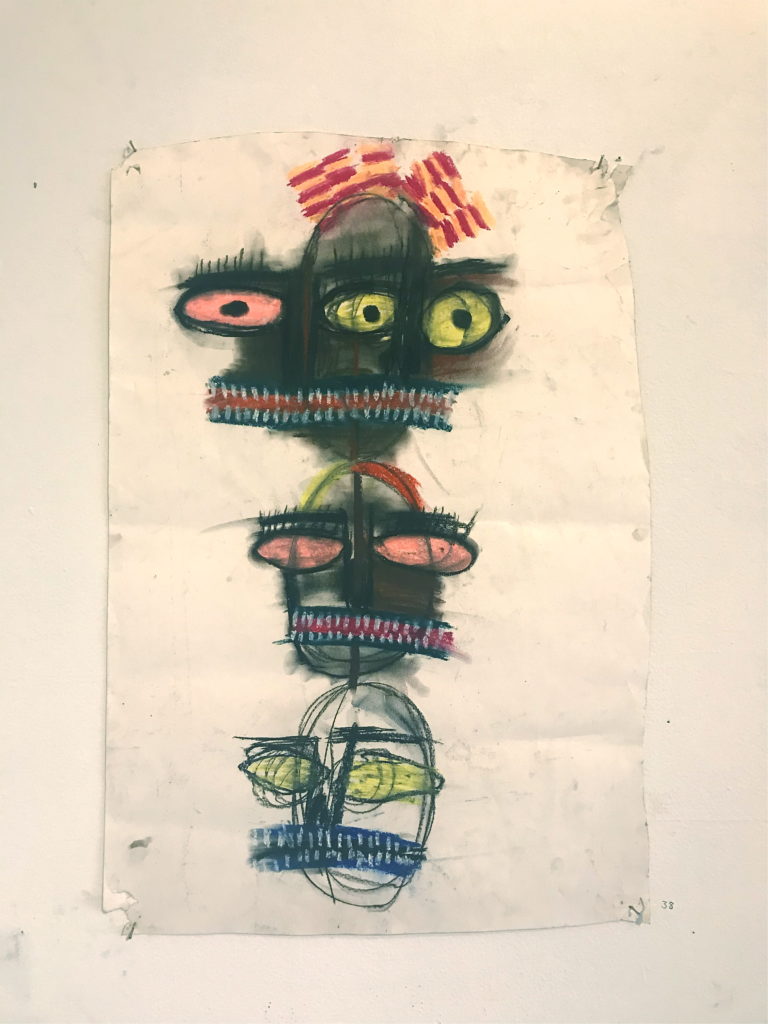

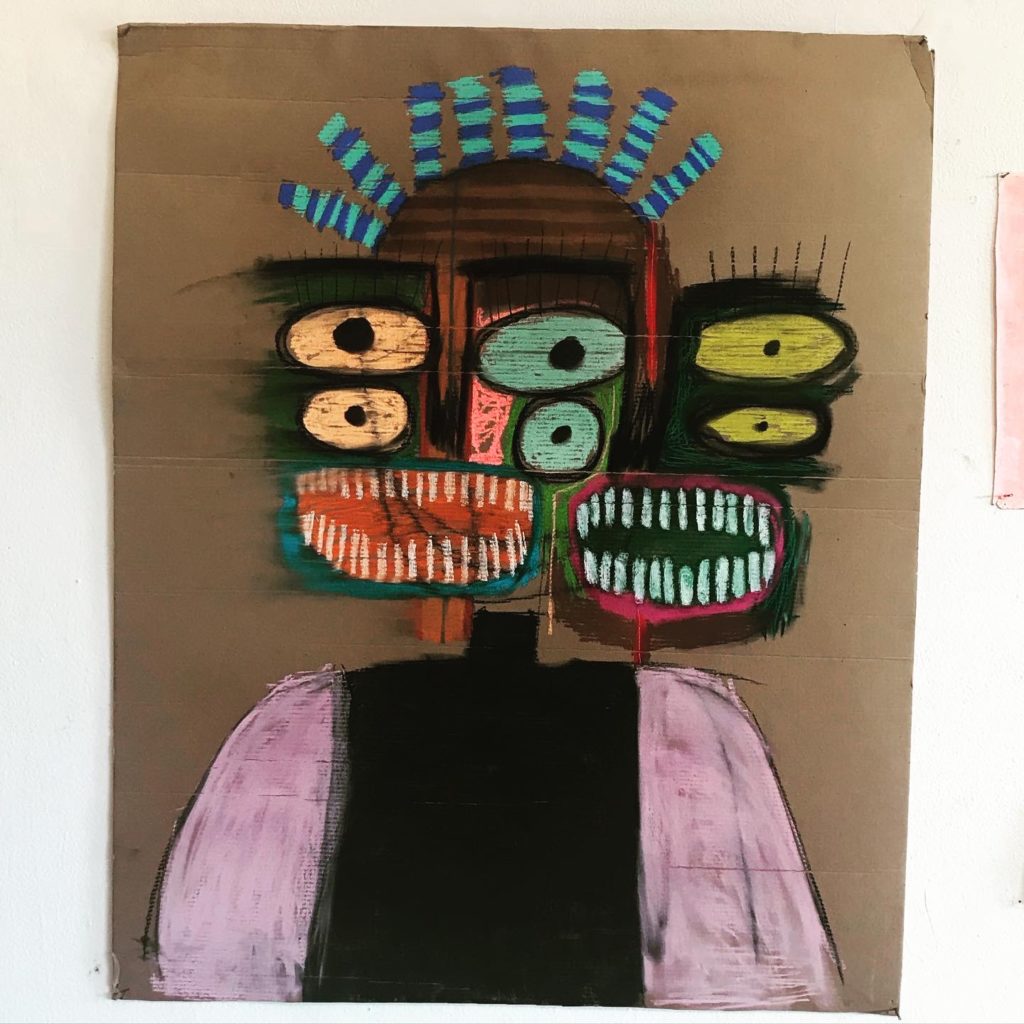

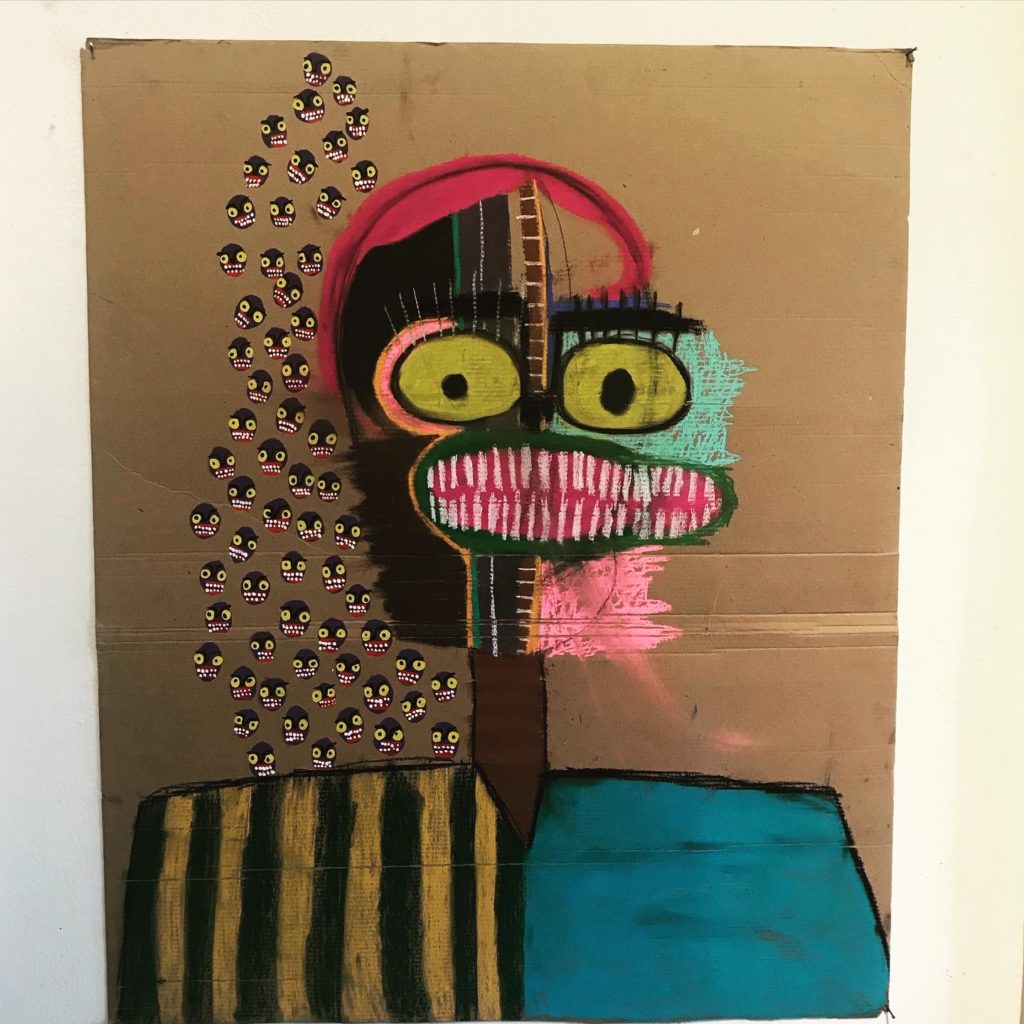

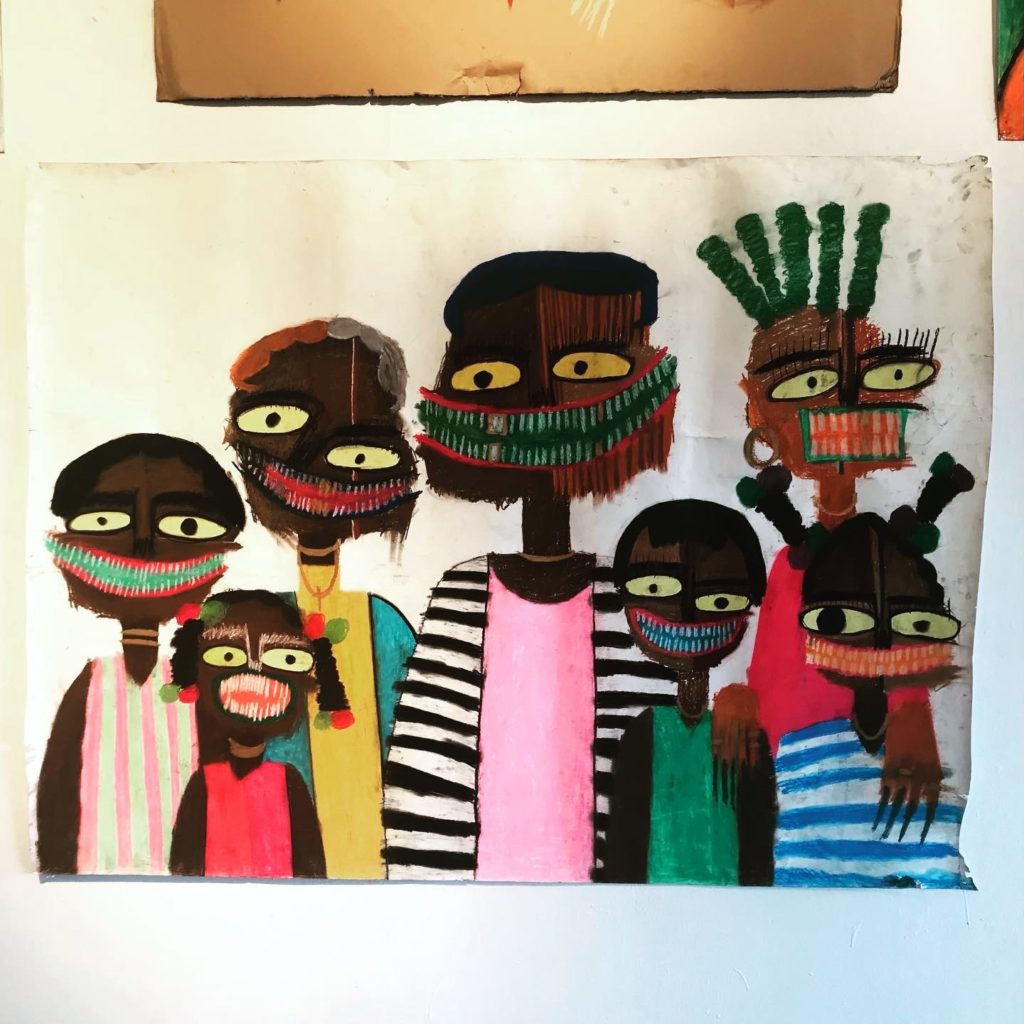

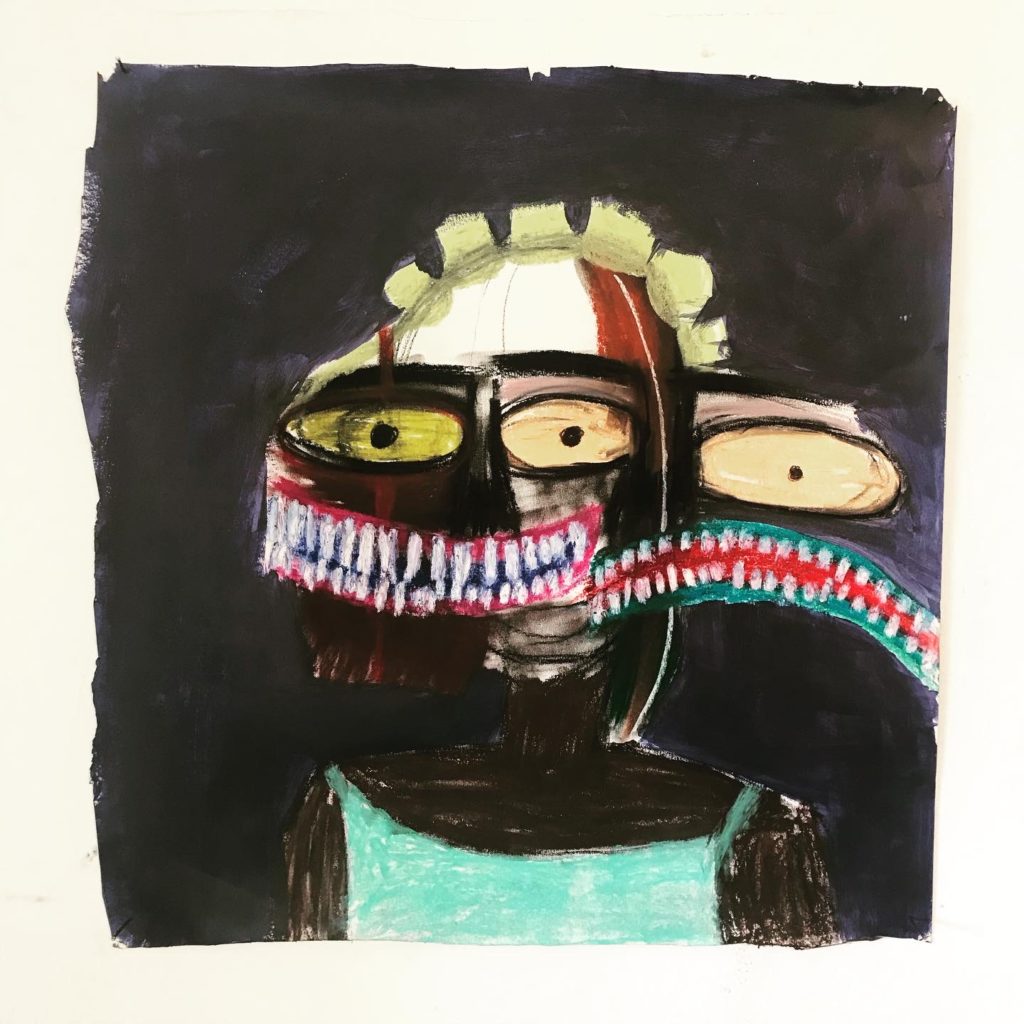

I like white space and space between artworks. When I first moved to New Orleans from New York—where my taste regarding gallery shows was formed—I would ask myself why why why, exhibitions here were always so overcrowded with work. Compared to New York, space is cheap and obtaining space to show art is much easier. Why was work seldom given enough breathing room? But, in this case, the crowd of portraits that surrounded me gained force in its numbers. The effect was overwhelming and felt intentional. It took me a while to focus on individual works. Each portrait was unique though it shared the characteristics of the others. Large often yellow eyes, open mouths, lots of teeth. Many of the figures had brown or black skin but some were striped. Some kept their arms to their sides and some had spaghetti arms, bonelessly moving through the picture plane. Each drawing was unique, but the humanity of the subjects felt blocked to me. I couldn’t and did not feel invited to know their personalities, moods. Even in the compositions that resembled uneasy family portraits, it was impossible to know how this family got along. These faces, their acidic, colorful attire surrounded me, the viewer, as a crowd, unified by something I did not understand.

In the novel Freshwater, by Akwaeke Emezi, a Nigerian child is born with a slew of gods within her, a kind of glitch in the metaphysical process of being born. It becomes a coming-of-age story about a character marked by what would conventionally be seen as plural personalities, genders, and maybe madness. The portraits on the walls shuddered with subjects whose features are inexplicably multiplied. Neither Adam nor I—we were both reading Freshwater—could separate the experience of the show from the book. The correlation felt uncanny.

It seems unlikely that this book had any influence on the show. Basquiat, on the other hand, may have influenced the artist. Her figures share the high color, the jittery lines, wild eyes, and prominent teeth. But with Ledet’s portraits, her voice seems like her own and if her style is derivative, well, I liked her portraits more than those I have seen of Basquiat. It’s true.

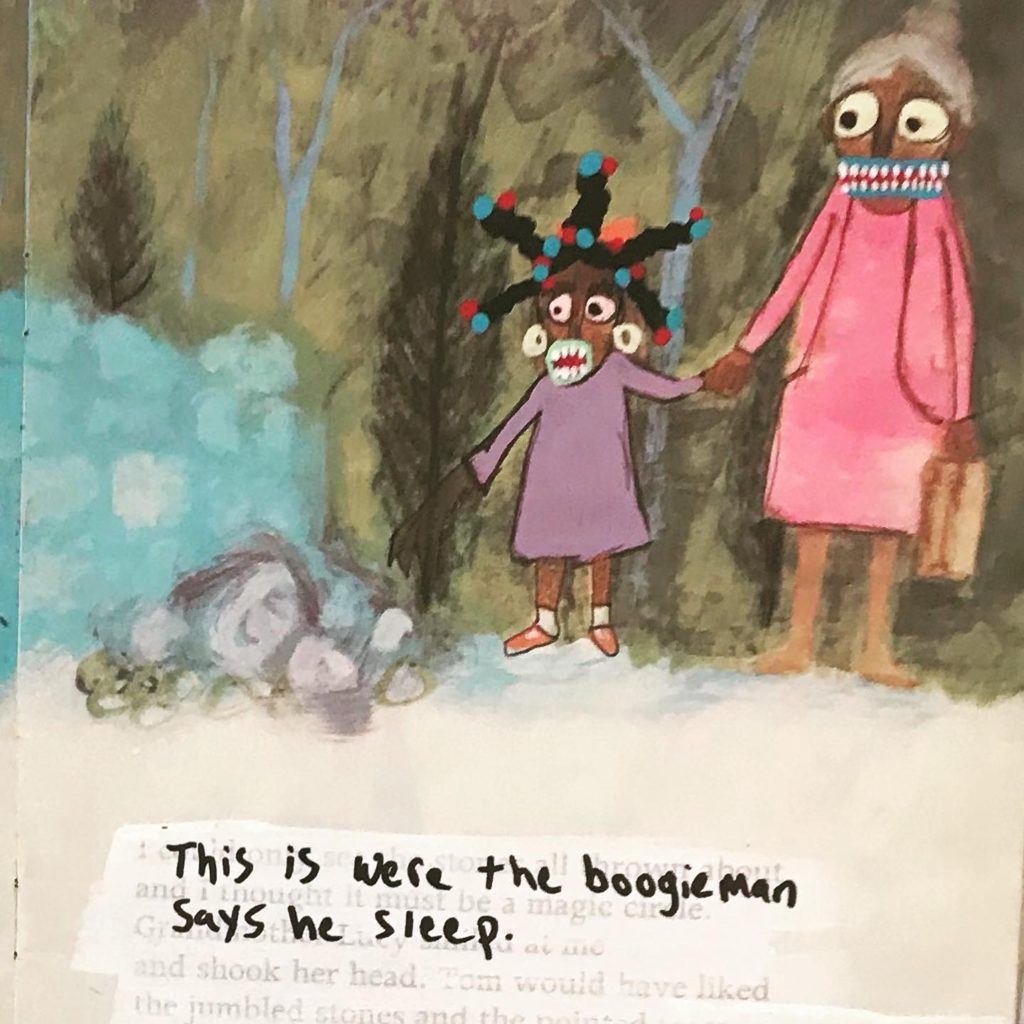

Sometimes I shake my head at poorly installed work; in Gabrielle Ledet’s show I admired it. Most of the works were nailed into the walls, an overly violent method of installation. The corners of many drawings were destroyed. The work felt like its verb-ness, the act that produced it, was more important than its noun-ness, that it was a thing to view, to take in as art. There was another piece I almost missed, an altered children’s book propped in a corner, low, not very well lit. In graphite on the wall next to the book the artist had written NOT FOR SALE. This piece made all the sense in the world, in the world of the show. Even the show’s title, the tense of the verb in Swam to the Moon, suggests a strange narrative, like a creative or delusional lie a child tells.

I was relieved when I left the gallery, taking off my mask, stepping into the quiet(er) fresh(ish) air of Saint Claude Avenue. The artist was outside taping (taping!!!) a large drawing to the stucco of the exterior of the gallery. I congratulated her on the show and in reply she asked if I had seen the flyer. I had. It was stuck to a telephone pole where I had parked my car across the street. Later, I would come across merch, shirts, and patches, and I felt a bit let down. But, hey, I drink my coffee out of a mug with an image of Hopper’s Nighthawks on it.

If art is not supposed to make you question your tastes, your reality, everything, all the art we would need could be found at Urban Outfitters. Art should shake us, upending our expectations. This show left me–and my preferences–shaken.

**All artwork Gabrielle Ledet, pastels, oil crayons, acrylic on paper/cardboard (2019/2020)

Emily Farranto is a writer and artist. She started the art blog Village Disco in 2015 and her children’s book, Animals Mate, was published in July 2020. She posts about the intersection of art and life on Instagram @thevillagedisco