Should Our Undoing Come Down Upon Us White, by Jill Osier. Bull City Press, 2013. $12, 36 pages.

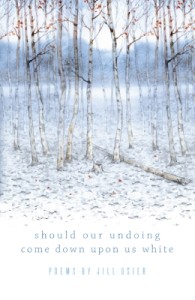

Robert Frost begins “Fire and Ice” by offering a choice between the two elements: one or the other, he says, fire or ice, desire or hate. Winner of the 2013 Frost Place Chapbook Competition, Jill Osier’s Should Our Undoing Come Down Upon Us White seems firmly rooted in that cold world eaten by ice, watching a relationship slowly buckle under its pressure. The design of the chapbook seems to support that cold tone, depicting a pale winter scene on its cover, but as we look closer, we see flickers of red in the branches—bright fall leaves that still cleave to the trees.

Osier’s work, though cool and reserved, is also inflected with moments of color and warmth: the red bird that circles the first and final poems, the orange of a fire, small intimacies between children and parents, between the couple whose relationship is tracked over the course of the series. In “Someday my stomach will be a museum,” Osier shows us this interaction:

When you come in, pissed because ice has swallowed

half the driveway and gnaws its way beneath the porch,

you’re starving and smell of the hay bales you’ve put down

to stall it. I feed the fire until you’re shirtless

while you cook, your shoulders

soft bitable rounds.

The speaker and her lover work in conjunction to stave off the cold, and their efforts feed their passion and their closeness.

But moments like these serve mainly as a foil, highlighting the invernal landscape, giving a sense of its crushing cold, its sameness, the stress that its circumscription must place on the heart. The opening poem, “The Sea of Too Far is Unmapped,” a postmortem of a failed relationship, lends a certain amount of suspense to the reading of the rest of the chapbook: who is this couple and how did they come to this point? Who is the speaker and how is she defined within the relationship and without it?

My first encounter with Osier’s work was several months ago when her poem “The Horses are Fighting” was featured on Poetry Daily. That poem, as well as the others I found online, was characterized by concentration, the minimum number of words for the maximum impact. Osier writes,

They stand scattered and not

facing each other. Like black-eyed

susans lining the highway, or sisters

angry in some small kitchen.

Within this one quatrain, the trajectory of the poem veers from one simile to another, each a discrete, compelling image. The poem then takes a larger turn in the final quatrain, revealing its context: the speaker is returning from a funeral and admires the way that animals are “content with any fresh mouthful.” “Horses” and many of the Osier poems available online, seemed themselves to be animals: compact, powerful beasts only half-domesticated, prepared to turn and bite.

I was surprised, then, by the poems I found in this slim collection: they are reserved and muted, lacking, for the most part, the lucid, dramatic leaps I’d come to expect. The poems themselves are hushed, relying on classic motifs: the changing of seasons, the flickering of a fire, the heart. But if these poems have fewer pyrotechnics, their subdued style is perhaps more appropriate for her subject: during winter, life becomes interior; in a relationship going wrong, the individual turns inward as well, reliving and reviewing.

The speaker in Osier’s poems is hesitant to name and voice her situation—Should Our Undoing’s first word is “maybe.” In “Obscura,” she compares the dark of winter and the smallness of the cabin she shares with her lover to a camera obscura, the ancient device whose mirrors projected an outer scene clearly, reproducing it within the box. The speaker asks:

…Didn’t it work

by its smallness, its dark?

I swear. I don’t know where

we would have needed to live.

Their home acts as a crucible, testing their bond, but rather than refining, purifying the situation, it renders it untenable.

The speaker is reluctant to clarify her own situation, but her observations of others are crystalline. The narrative moves forward propelled by vignettes featuring other characters, often isolated or in dire situations. In “Left to itself the heart could almost melt, mend,” Osier writes of an Amish girl getting off a bus:

She is maybe new to winter

this far north and wants to know

its depth. Its give. Oh,

be careful. It already has you

by the night of your dress,

violet-black with white-dotted print.

This girl is young, daring because she doesn’t quite know what she’s up against. Later, in “Spring has such tiny wrists,” we are given the perspective of a girl in a correctional facility, staring out the window as her breath fogs the pane, planning an escape.

In Osier’s penultimate poem, “Little towns shining in the distance,” the speaker is newly confident, traveling alone. Much like the speaker of Adrienne Rich’s “Song,” she seems to relish her fluidity and lack of roots. The cold of winter is giving way to spring. What before had been solid, stuck, becomes fluid and the self is revived.