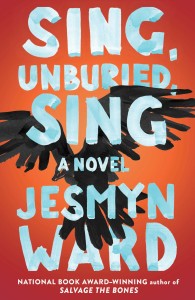

Sing, Unburied, Sing, by Jesmyn Ward. Scribner, 2017. $26, 304 pages.

Award-winning novelist Jesmyn Ward has been called both “the heir to Faulkner” and “a failed poet.” The former comes from a glowing piece in Time magazine about Ward, and the latter comes from the author herself. When asked about her lyrical writing style, Ward often answers “I’m a failed poet.” In theory, this means that Ward repurposes her love for poetry—especially repetition, imagistic fragments, and long, rolling metaphors—into her prose writing. It’s a fair assessment of her process, why she chooses certain words, why her characters’ inner monologues often have rhythmic, hypnotic effects. But, respectfully, I disagree with Ward’s diagnosis of poetic failure. In fact, I would argue that poetic voice is at the beating heart of her 2011 breakthrough novel, Salvage the Bones. Even after winning the National Book Award, Ward never got too comfortable with herself as the next visionary American novelist. In six years, though she wasn’t publishing fiction, Ward was devoting herself to chronicling racial injustices, both those from her personal experience and the high-profile cases of the last several years involving use of deadly force by the police. Her memoir, Men We Reaped, tells five stories of different young men in her life, including her brother, each killed in the span of four years. Last year, Ward edited a collection of essays (The Fire This Time) which drew its title from James Baldwin’s 1963 seminal work The Fire Next Time, two essays examining the role of race in American culture.

Given this background, it comes as no surprise that Ward’s newest novel, Sing, Unburied, Sing, explores a profound sense of racial disillusionment among a small, low-income family living in rural Bois Sauvage, Mississippi. Bois Sauvage, much like Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County, is a small fictional town in the Gulf Coast region and the recurring setting for Ward’s fiction. Ward’s focus on her home region has become an anchoring tool in her fiction, grounding both novels with a strong sense of place. In Sing, the town and surrounding areas are further compartmentalized into neighborhoods oftentimes delineated by race and class status. JoJo, the thirteen-year-old protagonist and lead narrator of the story, is acutely aware of the politics that govern his hometown, despite his nascent age. Sitting in the backseat of his mother’s car, heading north, he muses, “Some of my friends at school have people living up there, in Clarksdale or outside Greenwood. What they say: You think it’s bad down here…What they mean: Up there? In the Delta? It’s worse.”

Much like Esch in Salvage the Bones, JoJo is thrust into adulthood and self-sufficiency as a child, driven there by the absence of his parents. His mother, Leonie, is another of the novel’s three orators. Leonie is driven by her own self-interest, a codependent relationship with her children’s father, and the escape she achieves through drug addiction. She has two children with her longtime boyfriend, Michael, whom she met in high school. She is black and he is white. He is also incarcerated for drug-related offenses at the onset of the story. JoJo and his little sister Kayla, 4, share a connectedness forged by experience and necessity. The guardians in their lives are not their parents, but Leonie’s parents, Pop and Mam, who step into their roles as caretakers when Michael gets locked up, and they no longer feel they can trust their own daughter to keep her children safe. When Leonie and her friend Misty make a clandestine pit stop on the way to collect Michael from the state prison, JoJo sees a familiar-looking old shack set up just behind a small, shabby house: “There are tables with glass beakers and tubes and five-gallon buckets on the ground and empty cold-drink liter bottles, and I know I’ve seen this before…The reason he and Leonie fought, the reason he left, the reason he’s in jail.” JoJo’s only true father figure, Pop is an oracle or a superhero in his grandson’s eyes. The book opens with JoJo following Pop outside to the woods, where he plans to slaughter a goat to barbeque for JoJo’s 13th birthday: “I try to look like this is normal and boring so Pop will think I’ve earned these thirteen years, so Pop will know I’m ready to pull what needs to be pulled, separate innards from muscle, organs from cavities. I want Pop to know I can get bloody.”

JoJo may resemble Esch in his premature self-reliance, but one quality differentiates him, and several others in Sing, from any of Ward’s previous characters. After the enormous success of her previous novel, Ward could have delivered another family drama in much the same mold, maybe even replicating that success. But, she didn’t. Instead, Ward raised the stakes by traversing the uncharted territory of magical realism—much to her, and the story’s, benefit. Leonie, JoJo, his grandmother Mam, and even baby Kayla are gifted with magical abilities, which usually manifest as different “voices” or inner monologues that connect them to nature.

Perhaps the eeriest, most haunting sequence in the novel occurs in a flashback when an even younger JoJo watches his mother storm out of the house, leaving him home alone for the first time: “You going to leave me here by myself? I wanted to ask her, but the sandwich was a ball in my throat, lodged on the panic bubbling up from my stomach; I’d never been home alone.” He watches Leonie drive off, and quickly gets spooked by the sounds in the empty house. He wanders outside to the woods, where Pop keeps the livestock. He can breathe easy with the whir from the animals keeping him company—until he hears them speak. From Pop’s horse, with head bowed, “I could leap over your head, boy, and oh, I would run and run and you would never see anything more than that. I could make you shake.” Like any child, JoJo is shocked and afraid by what he hears, but “it was impossible to not hear the animals, because I looked at them and understood, instantly.” At an early age, JoJo learns that this ability is a part of him, inextricable from the young man he will become. This is only his first encounter with his mystical abilities, which also allow him to see specters of those who passed on long before his birth.

The characters, though brilliantly flawed, seem innocent at the same time, even naïve—helpless to their proclivities and histories. The harrowing death of her older brother, Given, in a murky and suspicious “hunting accident” throws Leonie’s entire orbit out of whack. Now, for reasons she might never fully understand, she sees Given resurrected, real enough to touch, every time she gets high. Seeing the ghost of her beloved brother doesn’t exactly comfort her–but it does soften the emotional and psychological embattlement Leonie feels, easing the trauma that her brother’s death wrought in her upbringing, her relationships, and her destructive habits. JoJo offers glimpses of trauma in his childhood, mostly stemming from Leonie’s actions (or inaction). “Leonie kills things,” JoJo says after reminiscing about the betta fish Leonie bought him when he was six–the fish that ran out of food, which Leonie was supposed to replace. This visceral combination of tragedy, grief, and otherworldly magic recalls Toni Morrison’s haunting novel Beloved. At its core, Sing is a story of trauma: how it can come from the most unlikely places, and how, like grief, everyone processes it differently. Underpinning the pain and the journey of the plot is the same symphonic clarity Ward brings to all her work. The title commands what the novel delivers—it sings.

Erin Little is an English major alumna from Loyola (’15). She currently works in editorial at the Crown Publishing Group in New York.