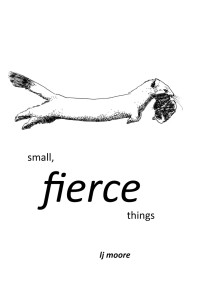

small, fierce things, by lj moore. Achiote Press, 2015. $12

While it might be a stretch to call the short stories, vignettes, flash fictions, and drawings in lj moore’s small, fierce things fables, fables nevertheless provide a useful lens to read moore’s book. As the title suggests, many of the stories in the collection involve animals. Set in a world that sits just off center of ours, moore’s stories partake of a variety of magical realism. In these charming, funny, brisk tales—composed in lucid prose and sharply written sentences—anything can happen, including a number of drawings by the author that seem to comment on, and in at least one case, to be an intrinsic part of one of the stories. Small, fierce things uses the language of fairy tales and a seemingly light touch to investigate deeper themes of grief, loss, and longing.

Resonating with the authority of myth, “driftwood” seems timeless and of our moment: in Iceland, a Norwegian named Sigbjørn comes to work in a mill, where his co-workers torment him, eventually nicknaming him “sig the swede.” Badly disfigured in an accident, he retires to the seaside to live in seclusion, warding off freezing to death by burning the driftwood that washes up on the beach. As is characteristic of the collection, the catastrophic explosion that disfigures Sigbjørn and presumably kills many of his colleagues receives hardly any dramatic weight:

after a night of drinking, they try in their way to make him belong to them, suggesting various names until, in a fit of backhanded alliteration, someone jokes “sig the swede,” and the insult sticks. after the explosion, he moves from longyearbyen to a shack on an isolated stretch further along isfjorden. he begins again there as himself, sigbjørn.

A few surreal touches follow, and the story winds up with the poetic image the title suggests, as we discover the driftwood that washes up on the beach—and that Sigbjørn burns “to remain himself” and to stay alive—is “a gift sent from his home,” that left Norway long before he did, in fact, before he was born. Whimsical and resonant, the nicely accomplished story packs a lot into its three pages and rewards careful rereading.

Likewise, “otter and wolf” recalls some of Robert Walser’s painterly miniatures, as the two animals of the title pursue the moon’s reflection on a lake. Like the entire collection, the story bristles with empathy for outsiders such as the maimed Sigbjørn, or in this case, otter:

it was said that otter was not right in the head. she ran toward loud noises. she jumped from steep snowbanks that dumped out onto the highway. she shoved her nose into piles of scat, into cooling campfire embers, into snake holes.

Indeed, that seems to be one of the collection’s themes: encompassing empathy for those small, vulnerable—and sometimes, fierce—things of the title, whether human or animal. After a chase, from the safety of the lake, otter observes the moon caught—finally—in wolf’s eyes. One of the most purely fabulist stories in the book, “otter and wolf” nevertheless withholds the kind of moral we expect from fables and has as much in common with Walser’s modernism as it does with the Brothers Grimm.

That sympathy for outsiders extends to the book’s human characters, like Lucky, contemplating blue suicide—“rushing the cops,” “the thump and sting of bullets followed by the beloved quiet and the relief of weightlessness”—in the story “how it came to this.” Told backward, the narrative traces Lucky’s disintegration through a series of unfortunate occurrences, his life unraveling in reverse. Paradoxically, the structure of the story reinforces the cause-and-effect logic so integral to the conventional plot it eschews. Yet, the story resolves not to a triggering event, but to an image, Lucky’s mother looking out her bedroom window:

a blonde, blue-eyed baby, seated in a lotus position, is floating outside. the window is on the second story. she asks the baby what it wants. it says, i’m your baby, let me in.

Perhaps Lucky’s inexorable downhill slide begins even before birth.

Robert Walser—a literary precursor to Kafka who ended up in an asylum (“I am not here to write, I am here to be mad,” he famously declared, though he was writing, anyway)—forms an apt point of reference. The tales in this book defy easy categorization. Are they short stories or one of those weird, in between, not quite genres: flash fictions or prose poems? What about the drawings, which are often funny in their own right, and which sometimes form frontispieces or comment obliquely on the stories, or even serve as part of the texts themselves? The book seems to invite questions about genre while at the same time suggesting they’re not all that important. Through its language, the drawings, and above all a particular outlook and repeated motifs, the collection creates its own world.

Of course, that promiscuity of form constitutes a liability. If you like your fiction told from the middle distance, with fully developed scenes and chains of cause and effect, for instance—which is to say, what still passes for the contemporary American short story—some of what’s on offer here might frustrate you. In particular, a reader might want more: more detail, more understanding of what leads to Lucky’s showdown with the cops. Bypassing the accident in “driftwood” might be an interesting move, but there’s also a case for showing what moore skips.

But that’s clearly not moore’s project. And as Walser’s belated canonization suggests, outsiders don’t always stay outside. W.G. Sebald sees in Walser’s tortuous “microscript”—the painstaking miniature handwriting he used during the latter part of his life—“preparation for a life underground” as fascism began to cast its shadow. Similarly, we might wonder whether contemporary writers aren’t doing the same thing by going small: shrinking with the marketplace and the empire, perhaps anticipating the darker currents in our politics. The stories in small, fierce creatures empathize with misfits: with the least among us. They share an impulse with experimental writing, yet they are neither as rigorous nor as forbidding as works by avant-gardists of the past. Finely made, worthy of contemplation, they demonstrate above all an impulse—to again borrow a page from Sebald—to save what is vulnerable in us from whatever looms on the horizon.