Lately I have been noticing spray paint and thinking about spray paint. It might have started on Instagram, scrolling through images of paintings and noticing marks made in sprayed paint alongside marks made with the more traditional brush. Spray paint on an otherwise traditionally painted canvas can be a statement of irreverence, a disruption, a small revolt like in these paintings by French artist Mark Petrusa.

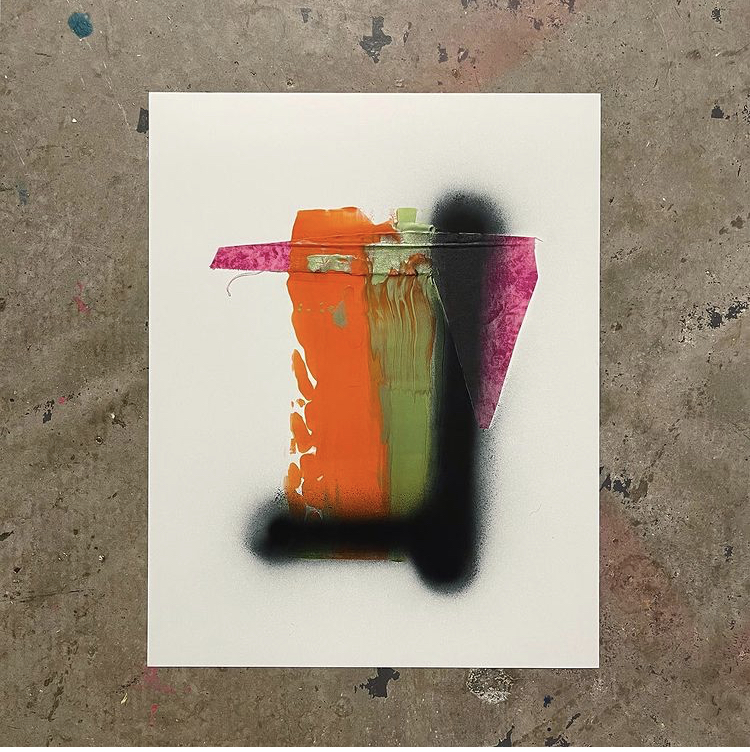

Or, it can be mark-making on equal footing with the traditional approach, a weight-bearing element like in these images of paintings by Forth Worth artist, David Wilburn.

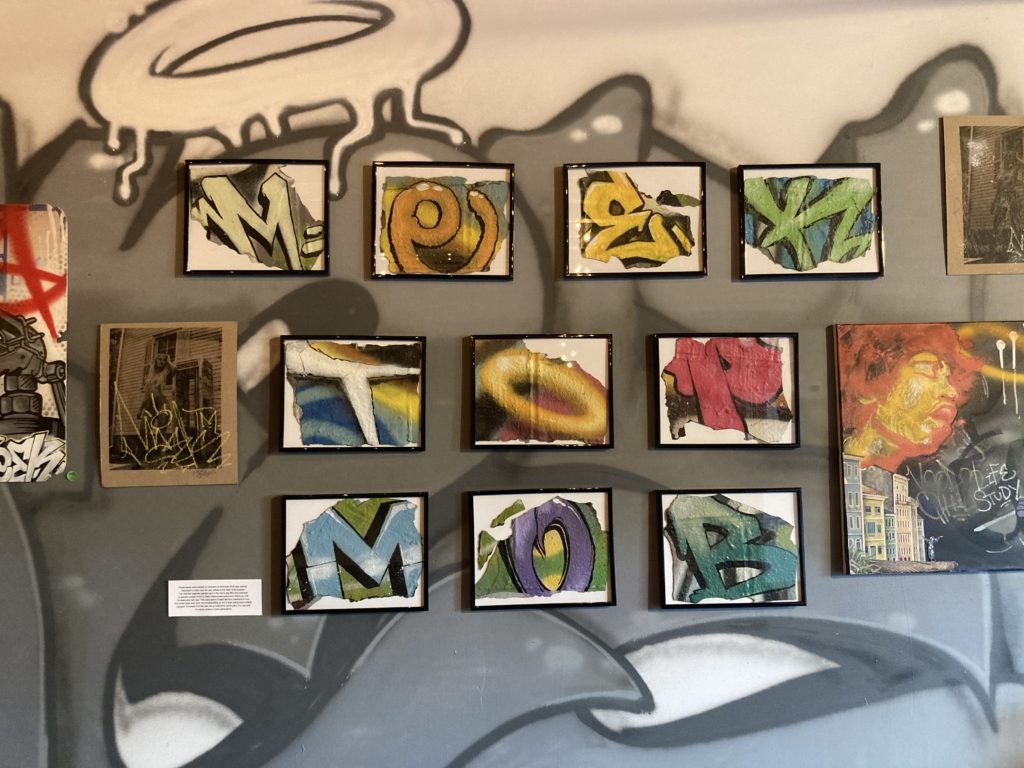

Maybe it was the Top Mob show at Under Nine Gallery in New Orleans late last month that turned my attention to spray paint. At the opening I was asking myself if bringing graffiti indoors is like bringing an outdoor cat inside. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. Speaking of outdoor cats, the law in Rome allows cats to live unbothered in the place where they were born. I like seeing the cats in Rome and I like seeing graffiti, not on the Roman Forum of course, but in those marginal spaces.

In the Top Mob show there were ten framed paintings that looked like torn scraps of a larger painting. The label next to them read:

These pieces were painted on remnants of the 9 wall which was recently destroyed to make room for new condos in the heart of the Bywater. The wall was originally painted back in the mid to late 80’s and continued to provide a public forum for New Orleans area writers and visitors up until its destruction last year. The many layers of paint still have impressions from the cinderblock wall…

Some of the earliest known art was spray-painted onto a cave wall. Our ancestor used a hollow bone or reed to blow pigment from the mouth onto the spread fingers of a hand in the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc Cave in France, the ultimate proto-I was here graffiti.

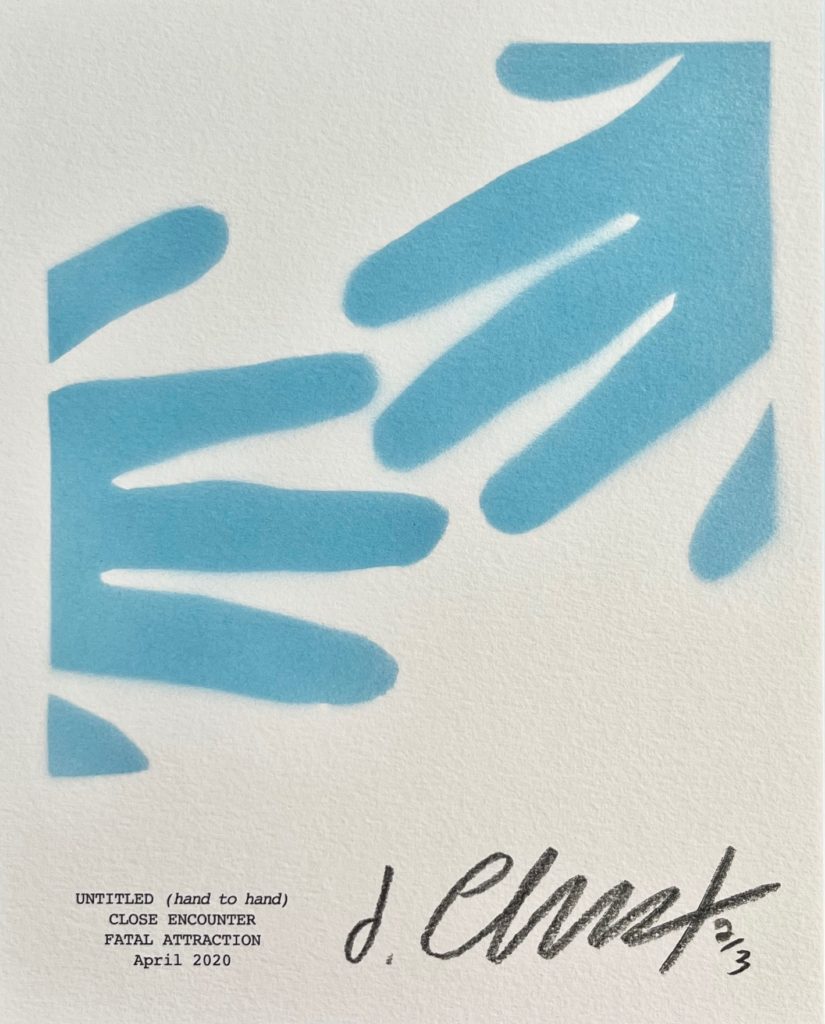

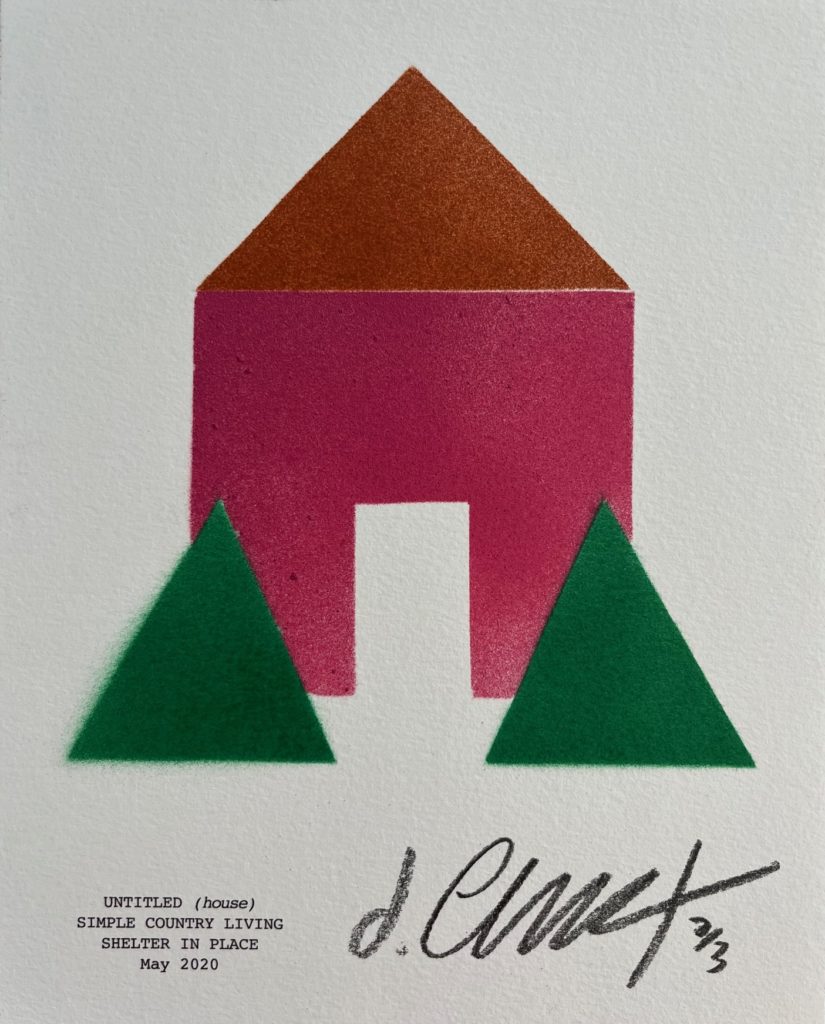

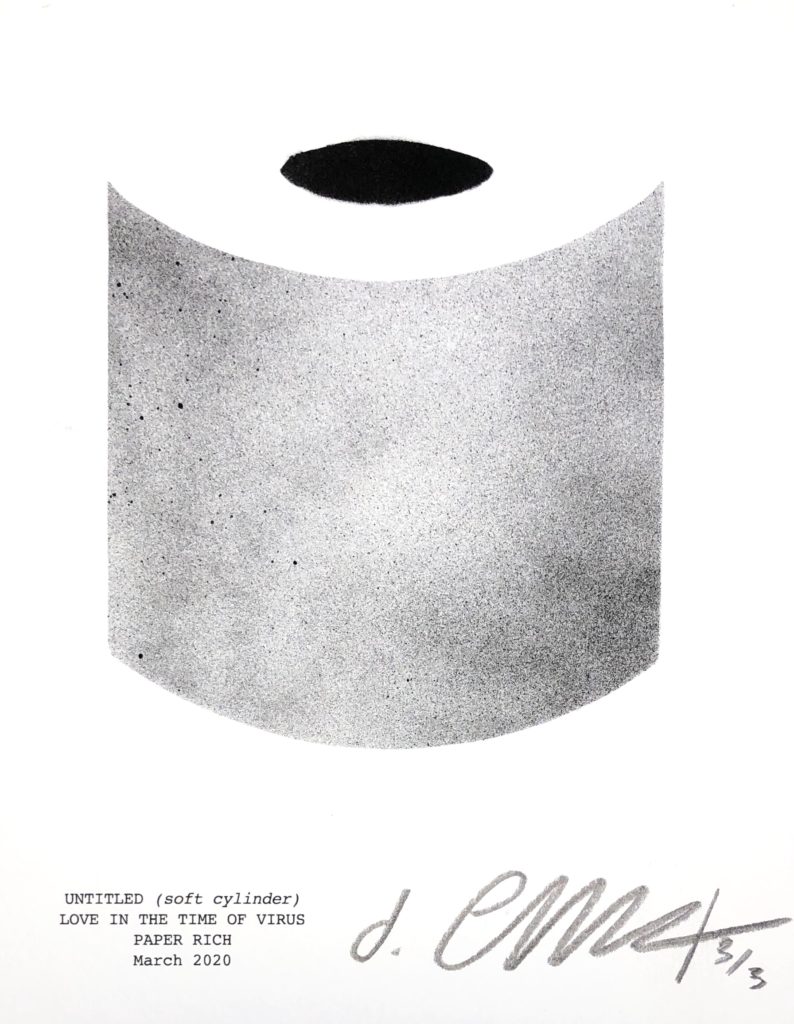

During the 2020 Covid lockdown New Orleans-based Dan Charbonnet kept a kind of visual diary of spray-painted stencils cut into glossy cardstock junk mail flyers. Presented in a tight grid, this series of sixty-one prints titled RESPONSE was shown in October at Good Children Gallery. For many artists there was an upside to the lockdown, a narrowing of options, a quieting of outside noise. These works are nervous and self-soothing, both pop and sincere, slick and pretty.

I am thinking about a stencil as controlled chaos, a corral for fast-moving paint. The dragmarks of a brush in hand are traded for a flat, kind of anonymous trace.

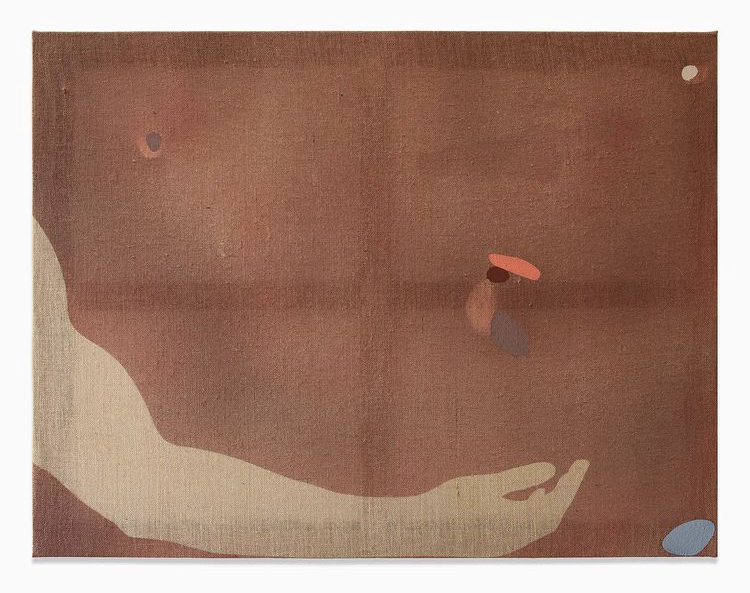

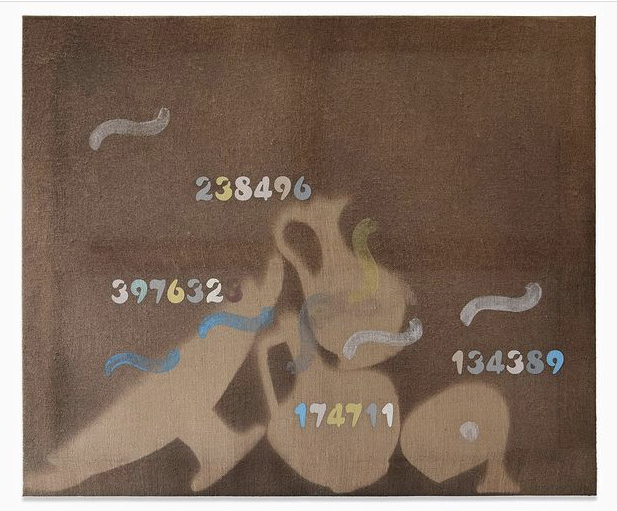

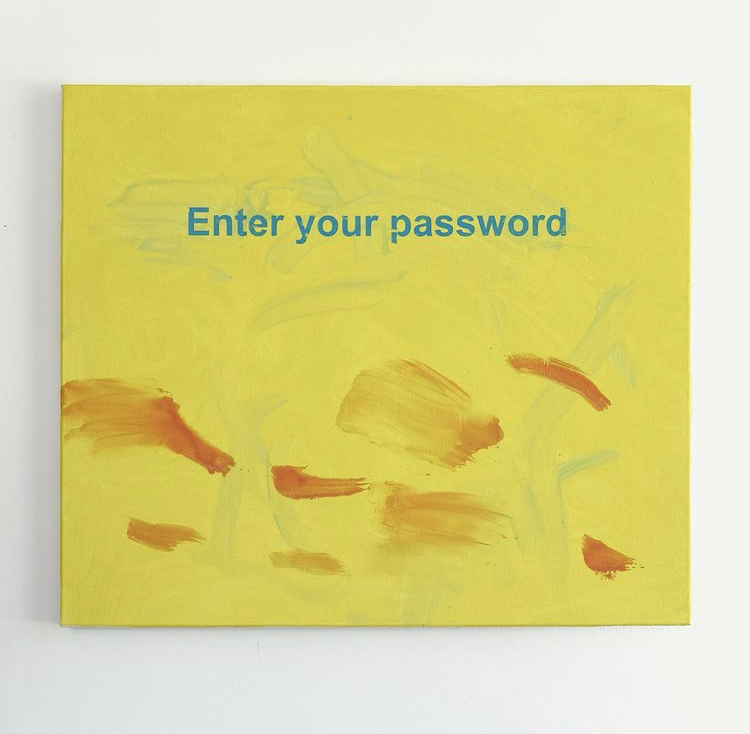

I sent a message to Nicolas Tourre in Paris asking about his use of spray paint. He replied,

I often think of an artwork is a kind of ghost of something else. That’s probably why in my airbrush paintings something leaves the body out first and makes it appear in details, forms or language in a second hand…

Miro Hoffman used both stencils and free-sprayed paint in “Waiting at the Bus Stop,” which I saw earlier this month at Le Mieux Gallery in New Orleans.

And then there are “outside activities.” This is how Czech graffiti writer Blackaut13 referred to his graffiti writing in an IG message. I asked if he also uses spray paint when he makes “indoor” paintings, which are for him a mostly a private activity. He said he preferred traditional methods. “I use spray mostly for my outside activities.”

Here in New Orleans there is a lot of “outside activity” to look at. If you live here, there is a face you may recognize. When I learned that the graffiti artist who went by the name Freya or Miss Max had died, I saw these faces everywhere. I looked through every photo on her Instagram feed and tonight I walked to one mural near where I live. The moon was out but it was still light. I had the uncomplicated thought, this is all so pretty. Paris-based photographer Jodo documents graffiti overtaken by time and flora. I’m not sure why, but I find these images reassuring. I stood there looking at Freya’s mural thinking about those photos of graffiti and that hand on a cave and the eternal impulse to leave a trace, to say (or spray) I was here.