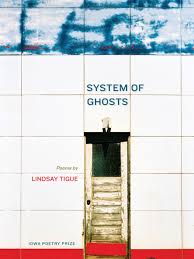

System of Ghosts, by Lindsay Tigue. University of Iowa Press, 2016. $20, 84 pages.

Lindsay Tigue is a devoted listener. System of Ghosts, her debut collection and winner of the Iowa Poetry Prize, is filled with fragments of reported language. A lover says, “I / never really wanted you.” A doctor asks, “how /is your mood today?” A woman calls, “I’m sorry” from behind closing elevator doors and, somewhere off to one side, a teenager says to his girlfriend, “show me your jugular.” People talk to one another in cars and planes and trains, trundling across a huge variety of territories. But every address is like the form letter sent to “current resident” or the artificial voice of the GPS calling out “turn left” over and over again: slightly removed, delivered as if from underneath the water or behind a pane of glass. All these snatches of speech have the effect of making the collection feel, aptly, less populated than haunted. Even the poems with living inhabitants seem crowded mostly with the memory of people, or, at the very least, with figures who want to reach out and touch one another but aren’t quite able, “all those passengers like ghosts crowding the station.”

All these snatches of speech have the effect of making the collection feel, aptly, less populated than haunted.

In a collection anchored by a series of poems called “Abandoned Places,” this pervasive sense of remove is not a weakness but the center of gravity. Tigue is uncompromising in her discussion of alienation and loss. Her language is spare and exacting as she describes a “boy crashed, his body / dead and mangled through windshield” or reports:

Across the country, a girl disappears

her parents desperately

speaking to cameras. Somewhere a man walks out

of his home, never to return…

She’s never showy or garish in her engagement with tragedy, but she refuses to look away. She insists we are built in some measure by what we lose, what we grieve, that part of being alive is being lonely.

I don’t meant to suggest, though, that System of Ghosts is simply a long litany of funeral marches and mourners and isolation. Each time Tigue’s poems threaten to collapse under the weight of darkness, she offers us, instead, something shockingly beautiful: “the arrested / arcs” of “gray, floating / animals in leap.” Her greatest gift as a poet is that, even as she knows the world is a fundamentally difficult place, she’s completely and utterly fascinated by it and an expert at transmitting that fascination to the reader. Her poems are full of the pleasure of fact and dense with a knowledge that is always animating rather than burdensome. Reading them, we learn “How to Care for Buffalo Horns” and about the “half-life of rocks, / the methods used to age this world.” We discover that “ The Blackfoot of the Plains had over / a hundred words for the colors / of horses” and find ourselves in Ancient Rome and then inside a U-boat bunkroom in a German submarine. If the towns of Tigue’s poems are abandoned, then they are also filled with a history and a geography rich enough to let us know they won’t stand empty very long.

The collection is at its best in when Tigue’s investment in the landscape and lineage of the world is not only intellectual but personal and emotional, when it fosters in her speaker(s) a commitment to trying to cross the chasms that divide us from one another. Wandering a museum of mummified body parts, the speaker of “Canopic Jars,” remembers when she “first heard the voices / of whales. Their calls through caverns of dark water,” and then thinks: “I want to create jars / for other hearts— ones as big, as impossible /as those of blue whales.” Here, biological fact turns over into desire as Tigue tells us she is busy imagining “Not our human hearts, / our heart-shaped hearts” kept “in a cabinet for winter.” Knowledge breeds a yearning to preserve what she loves, to preserve our very capacity to love.

Of course, this exercise is ultimately futile. The world changes and shifts; the things we build disintegrate. We are all mortal, and so will one day become ghosts who have no choice but to “settle in this shifting, / lose largeness. Lose any sense of it all.” But, for Tigue, it’s clear that the provisional nature of our lives is part of what makes them so extraordinary. Upon learning about the rift of Pangea a little girl cries because “It too beautiful, the way everything can / and will separate.” And in “Solitary, Imaginary,” a speaker, who spends her days alone delights in the momentary connection allowed by a loss of electrical power, the moment when she can ask her frazzled neighbors in the pitch dark street “Do you / have power?… Do you have light?” There’s something astonishing in the very transience of things, and even in the divisions between us and the tiny, quotidian ways we reach across them.

This is the great gift of Tigue’s work. She knows that being captivated by the things of the world is the surest path to surviving and to any kind of happiness. There’s “tragedy everywhere and / everywhere.” But ultimately her book of abandoned places and loneliness and distances, her System of Ghosts, insists: “I love and I love / and I love.”

Molly McCully Brown is a poet and essayist. Her collection, The Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded, won the 2016 Lexi Rudnitsky First Book Prize and will be published in 2017 by Persea Books. Currently, she is a John and Reneé Grisham Fellow at the University of Mississippi.