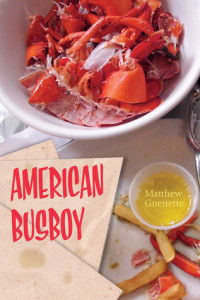

American Busboy, by Matthew Guenette. The University of Akron Press, 2011. $14.95, 64 pages.

American Busboy is an edgy take on the highs and lows of thankless work. Matthew Guenette dives deep into the service industry, unearthing the strange dynamics created by what many never question: a night out at a restaurant. These poems are told from the perspective of one of a restaurant’s lowliest workers, the busboy. While running between the front and back of house, he doesn’t interact with customers but observes the management, the servers, and the tourists with microscopic precision, finding humor, romance, and injustice in a place tastelessly called The Clam Shack.

The poems are cleverly titled with phrases that the service industry world revolves around: trainings, smoke breaks, and holidays. An image-rich book that draws strength from actions and reactions, Guenette’s poems are often fast paced and repetitive, mimicking the life of service industry staff and drawing the reader into this world. Guenette seems to borrow language from menu descriptions, such as in “–Memorial Day–” when he writes “you are encircled by sizzling / snapping scallops,” the alliteration is as cheesy as an Applebee’s advertisement.

Poems in this collection are not concerned with the positive portrayal of food and the serving of it; instead they center on gritty behind-the-scenes happenings. Food, when featured in a poem, often is done so in a revolting way, as seen in the poem “–Epic–” when a clam roll is described as:

pissing lemon juice

down the French

fries’

crinkled leg

These lines convey the attitude of the busboy, the disgust he has for the environment he finds himself in. Relationships between customers and staff are also explored throughout the book, through the eyes of the busboy who fantasizes in “–Smoke Break –” about customers “zip-tied & stuffed in / the trunk of a car speeding back / to Massachusetts.” This morbid fantasy shows that Guenette understands the stressed worker who finds comfort in imagining alternatives when escaping the hectic scene for a quick cigarette. By couching cruel realities of restaurant work in dark humor, his critique of an unbalanced relationship between the served and the server becomes easier for readers to swallow.

In addition to the clashes of status shown between worker and customer, the overall restaurant hierarchy is given attention. In “–General Attributes–” the origin of the word busboy is questioned. Guenette proposes that “It means nowhere in sight, / stealing your tips, / seeker of the waitress panties,” showing the lowliness of the position and milking its clichés for all they are worth. Priorities are questioned in Guenette’s poems as his verse often contrasts large ideas with minor restaurant problems. “–National Flag Week–” features a hostess in action “apologizing for disappointing fried clams / apologizing for fried clams that have underachieved,” raising the question of what it is to disappoint, and why one would care so much about a fried food not achieving its maximum potential.

Unrealized potential becomes a recurring theme in the collection. In “–Name Your Poison–” the busboy is shown to be:

belittled & battered & brain-

bashed out

bewildered & sorrowed

like something beached

waiting for the end

of a shift

This description, heavy on alliteration and quite violent, equates the busser with what he spends his time cleaning up: dead animals dragged out of the ocean. Despite this, or possibly because of it, these poems root for the underdog, showing the hung-over employee more favorably than the disgruntled customer. In doing this, Guenette takes the risk of alienating readers who may not appreciate the way he portrays customers, and the way he embraces some stereotypes of restaurant workers may be off-putting for service industry professionals who don’t indulge in drugs, booze, or have a general disdain for those that they serve.

This is an unavoidable risk, though, as the poems in American Busboy are concerned with giving voice to the unheard worker who is smart and quick-witted. One of the most enticing poems of this collection, “–The Weekly Week–,” makes reference to literary luminary Allen Ginsberg, borrowing from the opening lines of “Howl” to set the scene:

I saw the best minds

of my generation lobster-

bibbed

& buttered,

heard its voices

mushroom-clouded

& bused through

This portrayal of the busboy as not merely disgruntled, but as someone who is out of place and aware that he, like the fried clams being eaten around him, has underachieved and knows he has disappointed people adds more weight to these poems and opens them up for a more serious read. American Busboy portrays waitresses as powerful creatures, managers as incompetent assholes, and little things like clam strips as earth-shatteringly important. Guenette has taken status and flipped it: he’s analyzed what many never question, and has turned the busboy into a poet who could do more with his life but doesn’t.