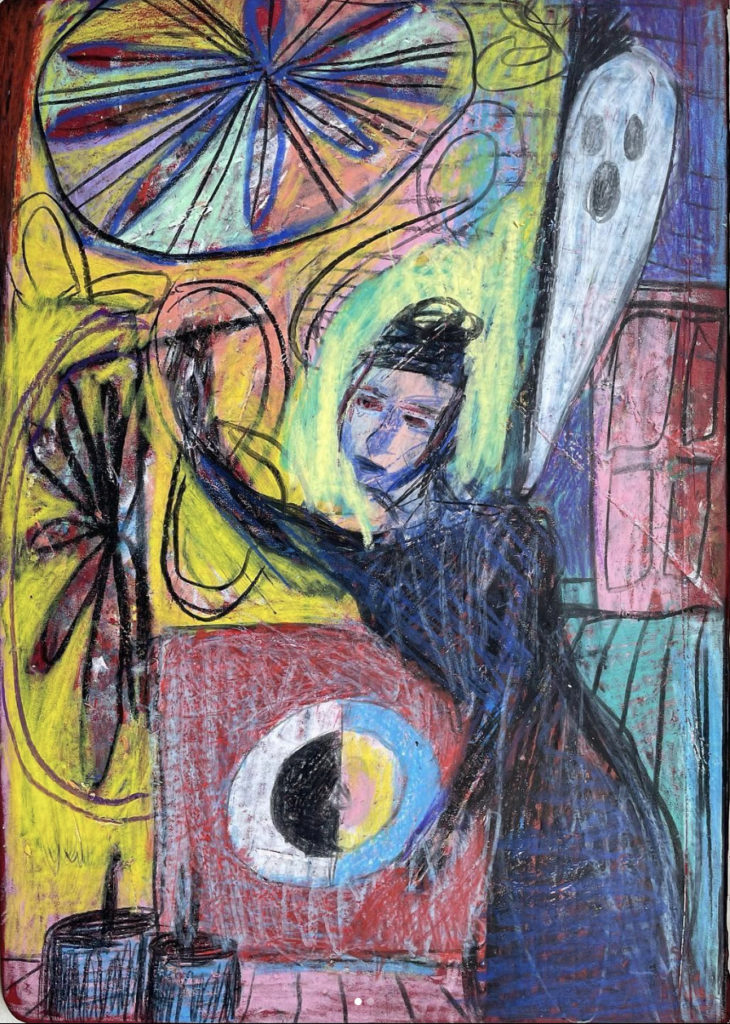

…Every artist who has spent a long night in the studio knows that eventually, the ghosts will come.

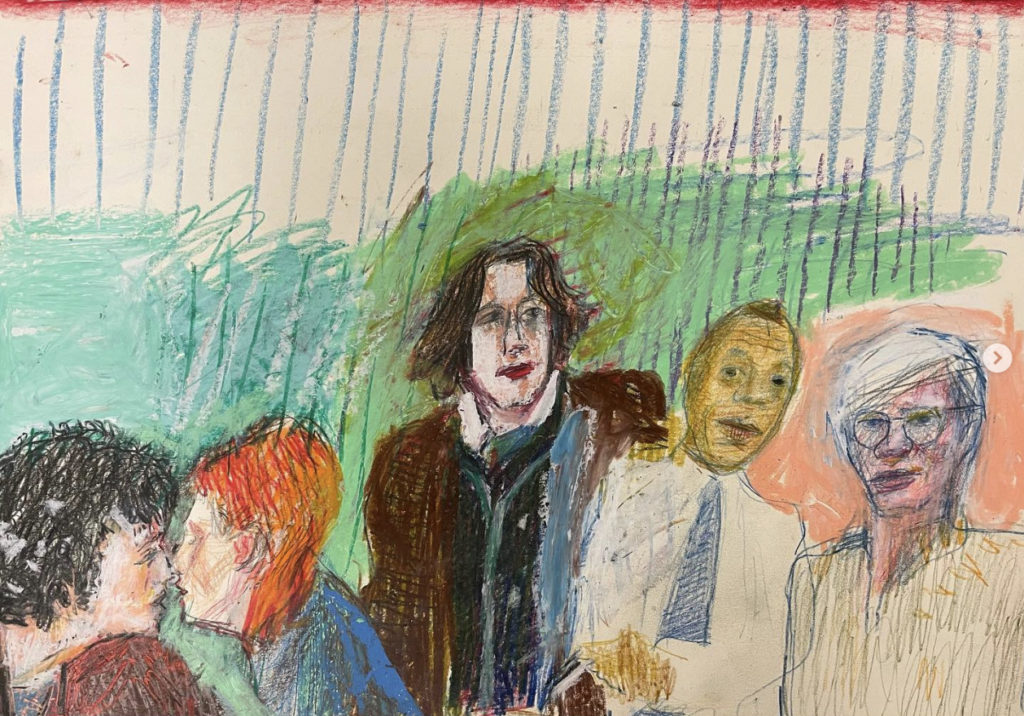

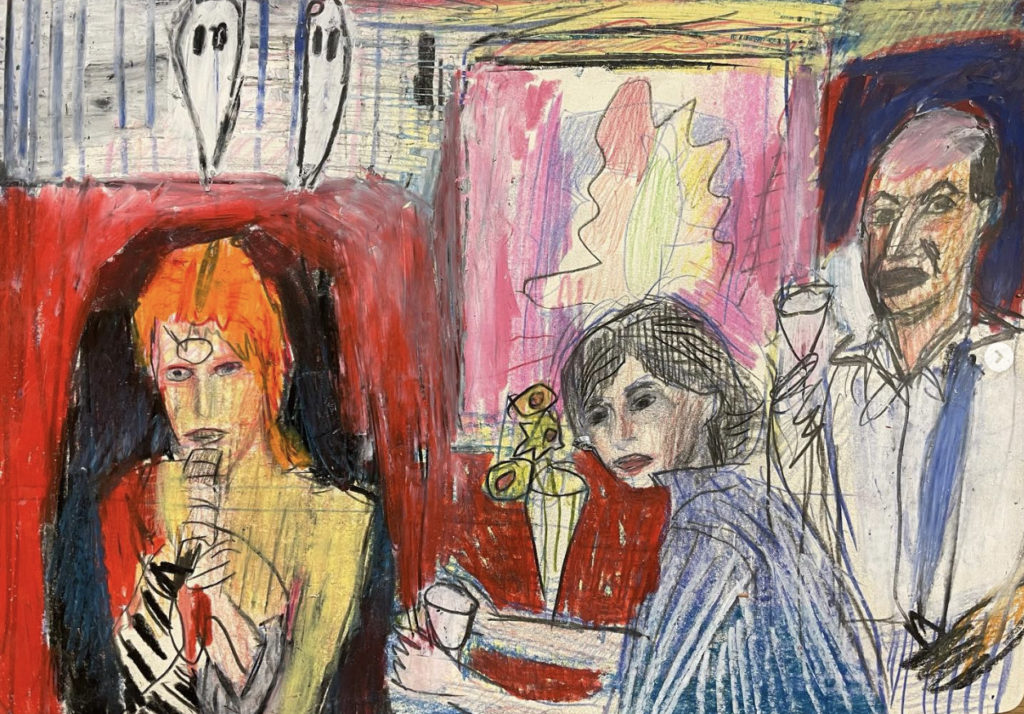

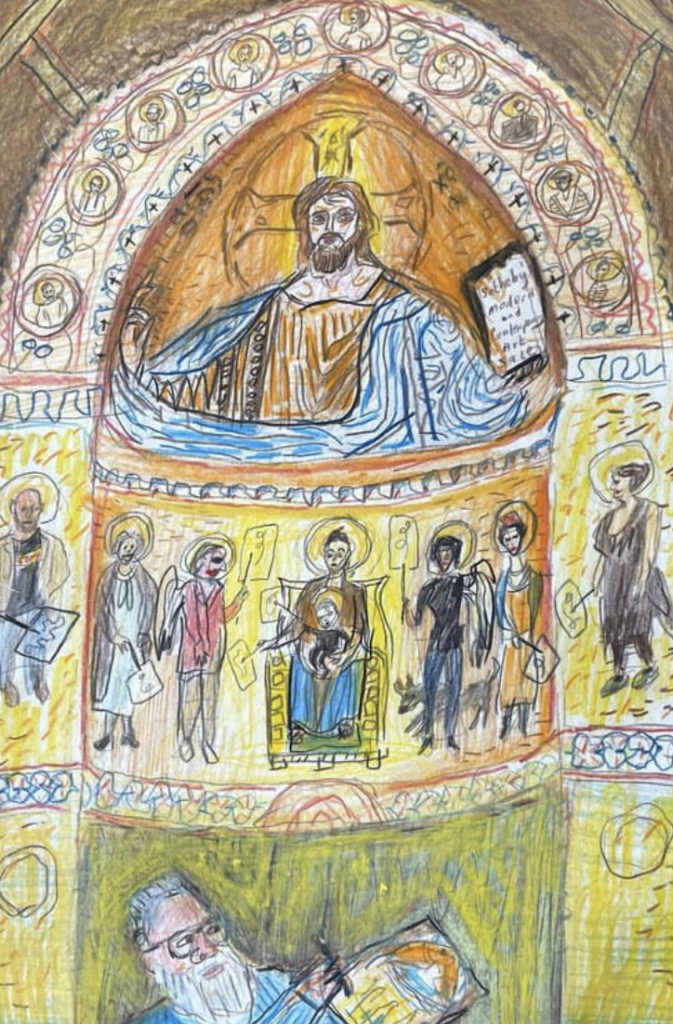

The traditional version of Art History taught at university posits a timeline, delineating eras that contain advancements in technology, named movements, and the introduction of new “isms.” Artists are born, work, and die on this timeline, the sum of their life in art summarized in an image or two. Matthew Collings’ version of art history is different, focusing on the artists more than the art, the specific rather than the vast, and the personal rather than the academic. The setting in many of his drawings is the studio, the place where art is made, rather than the church, palace, gallery, or museum. Collings draws artists (most dead as doornails1) in scenes from their lives (real and imagined) solitary or with other artists they knew or did not know in life. They meet in the colored pencil afterlife, bardo, or just in the mind of Collings himself, away from the noise and worldly priorities of the art world. Certain artist-spirits return again and again to Collings’ drawings, archetypes that influence the mood, tone, or meaning of the scenes they haunt.

The First of Three Spirits: Hilma af Klint

Hilma af Klint was an artist-mystic who died in 1944 at the age of 81. She was part of a group of women called “The Five” and is associated with the mystic religion, Theosophy. Many people now claim Hilma af Klint and not Wassily Kandinsky created the first abstract painting in Western Art.

In Collings’ vignettes, Hilma af Klint appears like a conduit between the living and the dead, between sincerity and branding, between the con and art’s potential to achieve authenticity. In a 2013 piece in Art Review, Collings “interviewed” the long-dead Hilma af Klint. In channeling the artist’s voice, Collings expresses his skepticism aimed not at her work, but at trendy enthusiasm which tends to ignore her actual creative accomplishment: abstraction. Collins wrote, speaking as Hilma af Klint:

You know, if you’re a painter you spend a lot of time getting things right, getting forms to be efficient so that whatever you’re hoping to get across can have a chance of being coherent, of actually communicating to someone. You’re basically narrowing down to a very visual priority. But in the way ‘the spiritual’ is understood in the age of consumerism, it is basically anathema to the ‘right’ or the ‘efficient’ in art, and it fits very well with most people’s – including professional art people’s – completely unvisual idea of art at this moment.

When we spoke via video, Collings said,

Is Hilma af Klint the triumph of hysteria or is she the defeat of hysteria?…When I’m drawing her in a certain way and not another way, I think what I’m putting aside is something false and what I’m going for is something I can believe in.

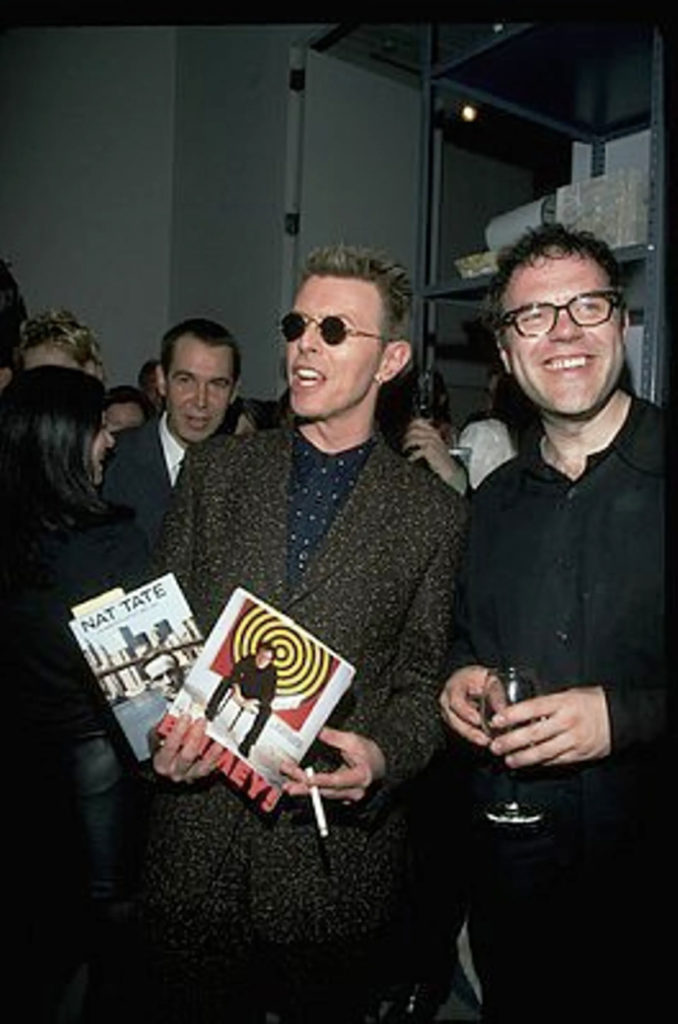

The Second of Three Spirits: David Bowie

In 1997 David Bowie’s new company, 21, published Matthew Collings’ book Blimey. In an article in The Art Newspaper, Collings describes meaningful and touching exchanges with the pop icon over the years. In these drawings, David Bowie, who died in 2016 at the age of 69, is ageless, outside the bounds of lifetimes, mixing with everyone from Claude Monet to Oscar Wilde. Collings captures David Bowie’s beautiful strangeness, a bright star sparkling against the self-serious atmosphere of Art.

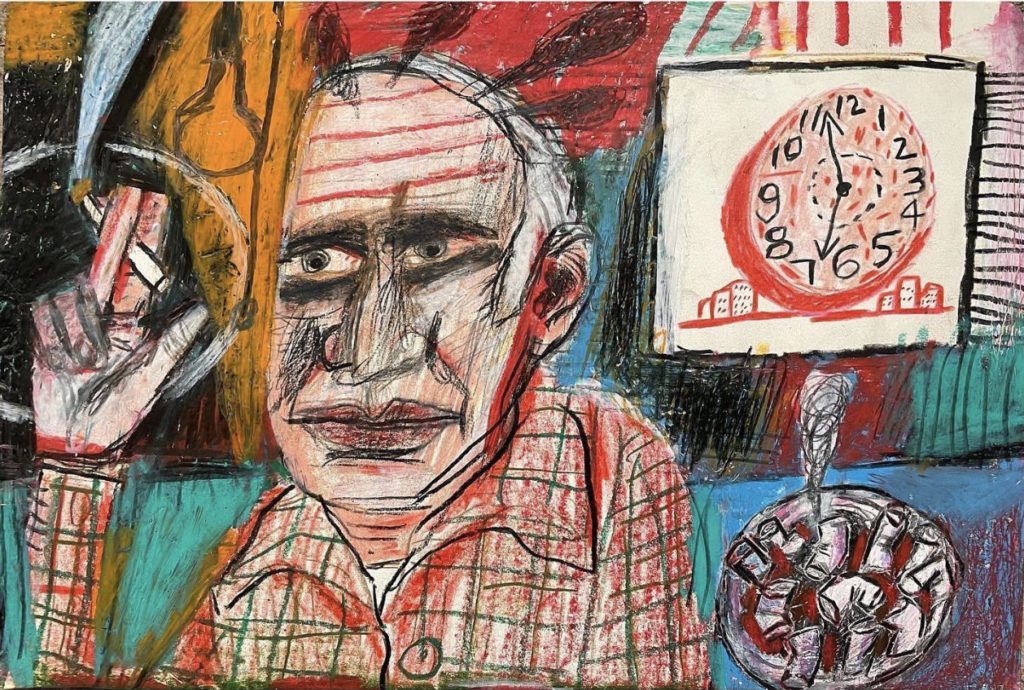

The Third Spirit: Philip Guston

The heaviest of the three ghosts, the most serious and solid-looking, is Philip Guston, who died at the age of 66 in 1980. Philip Guston gained notoriety as an Abstract Expressionist in New York in the 1950s. In the later 1960s, when Guston defected from Abstraction and returned to a kind of realism, mixing painterly brushstrokes and cartoonish imagery, the crowd booed. Critics Hilton Kramer and Robert Hughes panned his new style. Guston’s stylistic one-eighty happened against the backdrop of 1960s cultural upheaval and was fueled by the desire to address issues of social justice in his work. And yet, Guston would not let his work be put into a drawer or oversimplified as political art with a clear message.

This open-endedness was part of the reason why, in 2020, four museums issued a joint statement announcing a major retrospective of the artist’s work would be postponed until 2024. They identified concerns that the work might be misinterpreted in the context of the racial justice movement that began with the killing of George Floyd. To many in the art world, this was an example of toxic sensitivity, misled corporate-style cowardice, and a muting of art’s power to speak truth. In our conversation, Matthew Collings referred to Guston as “the moralizer.”

In a 2021 piece in Artforum, Robert Slifkin wrote,

In 1980, the final year of [Guston’s] life, he repeatedly told the story of Willem de Kooning’s taking him aside on the exhibition’s opening night and saying that the work’s true subject was “freedom.”

In his lifetime, and even now, Guston is a torch-bearer of creative and moral autonomy, the freedom to follow one’s own social and aesthetic compass.

In Matthew Collings’ drawings, Guston sometimes feels like a proxy for Collings himself, standing for the values (artistic and political) they share. Like Guston, Collings has embraced both abstraction and figuration. Both artists eventually left their capital cities to live in the country. Both buck the consensus model of participating in the art world. And both Guston and Collings criticize the ills of capitalism, fascism, and systemic hypocrisy with a cartoonish (or illustrative) hand and a dash of dark humor.

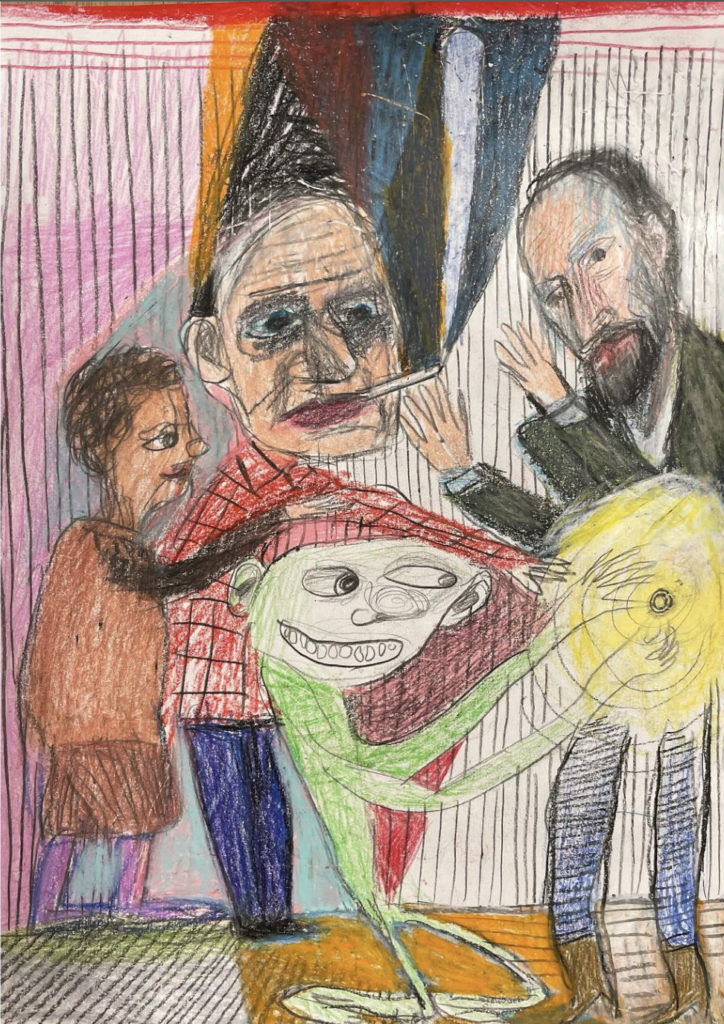

In one drawing that actually made me laugh out loud, Collings depicts Philip Guston with The Hobbit, the artist Bruce Nauman, and Gollum. The caption reads “One ring to bind them all.” This drawing pokes at something–I’m not sure what–maybe the gold at the center of the art world, glowing like Mordor. Ha!

When Matthew Collings sets out to make a drawing, he does so without much of a plan. Sometimes, he told me, he starts by drawing an eye and goes intuitively from there. He explained,

When I’m drawing and I’m drawing carelessly, and I have an empty mind, I think I’m probably expressing a serious thought…I haven’t the faintest idea when I make the first mark what the look of the drawing will be or what the mood of it will be. I’m always drawing Hilma af Klint. I feel I’m always joking about her. Not maliciously it’s just that the whole story of her is so absurd I’m literally drawing the absurdity of spirits telling someone what to paint…

I responded, speaking slowly, smiling,

It’s funny…you were saying your mind is empty…and you don’t know where these come from…and in a sense, you are in your own séance…drawing someone in a trance, taking from the ether while, one could argue, you are in a trance taking from the ether…

Matthew Collings, understanding where I was going with this as I spoke, began to smile. Then he laughed and said, “That’s a lovely way of putting it…”

(Coming Soon, Part 3: The Ecstasy of Color…)

1“I don’t mean to say that, of my own knowledge, what there is particularly dead about a doornail. I might have been inclined, myself, to regard a coffin-nail as the deadest piece of ironmongery in the trade.” Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol.