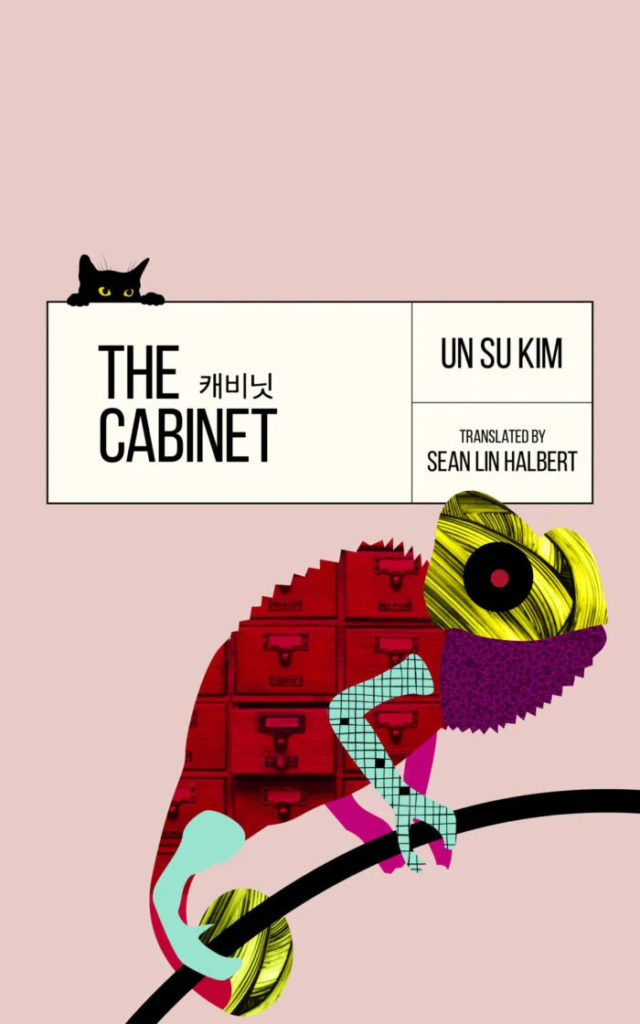

The Cabinet by Un-Su Kim, trans. Sean Lin Halbert. Angry Robot, 2021. $14.99, 304 pages.

“If by some chance you intend on reading this book to the end, it would be best if you rid yourself now of any fanciful or romantic expectations, because if you have such expectations, you will only see that or less.”

So begins ‘The Cabinet’, Un-Su Kim’s debut novel. Winner of the Munhakdongne Novel Award, South Korea’s most prestigious literary prize, it is his second novel to be translated into English. Translator Sean Lin Halbert has won multiple awards for his previous work, including the Grand Korea Leisure Award and Literary Translation Institute of Korea’s Translation Award for Aspiring Translators in 2018.

‘The Cabinet’ follows the day-to-day life of bored office worker Mr Kong and his maintenance of a filing cabinet which documents “symptomers”: people whose strange experiences mark the beginning of a new species, who “exist between the humans of today and the humans of the future”. The novel integrates the stories of these symptomers with Mr Kong’s daily narrative and vignettes from the interviews stored within the cabinet. Ultimately, this makes for a book that reads like a disjointed collection of short stories: it’s not until two-thirds of the way through the book that any real plot begins to develop. That said, the stories themselves are beautifully written, with one of my favourite lines appearing in the very first chapter: “They hung criminals up in high places where there was good sunlight and plenty of wind so that the dampness of their crimes would evaporate in the warmth of the sun, and be blown away by the breeze.”

While strange, the first few stories are relatively light-hearted and narrated humorously – although I must admit at times to having found the narrator’s vulgarity to be distasteful: at one point, the perpetually bored Mr Kong amuses himself by playing and conversing with a coma patient’s penis, asking, “Hey, Mr Penis. Have you ever been used for anything else besides taking a whiz?” The stories become increasingly bizarre until the message is clear. This book is ultimately a discourse on the alienation of capitalist life.

The very premise of this novel is that “where there is immense environmental pressure, a species will be forced to evolve rapidly”, that “humans are becoming a footnote in the history of life on Earth” due to the “uncontrollable beast” of capitalism. Mr Kong himself comments that he’d like to be a fish underwater, where they don’t have demands or phones: which means a lot coming from a man who frequently complains that his workday largely consists of “I-would-rather-eat-dog-treats-than-suffer-this-boredom boredom”. This cynical view of office life in South Korea, where one receives a paycheck simply for “manning one’s post”, is pretty universal, and also our first hint of the anti-capitalist nature of the novel.

The torporers, symptomers who sleep for up to two years at a time before waking up full of energy and with all their ailments magically cured, further indict the system: “the entire modern economy is based on anxiety, and as everyone knows, anxiety is the mortal enemy of a good night’s sleep.” A man who finds himself turning into a toothpick while paying off debt wonders if “in the twenty-second century, people will live empty lives like vases and tables, unable to feel love, pain, or loneliness”. A woman whose spirit inhabits two bodies, one which works and one which plays, finds her working self burying her other body every day: “so many beautiful and happy selves have died, but that self which turns 2mm screws all day survives in utter monotony”. These gloomier narratives weave together a story of burn-out and detachment under the Sisyphean nature of our society that resonates just as much in the West as it does in South Korea.

The last few chapters take quite a sharp turn from the still and reflective nature of the rest of the book in a way that won’t appeal to everyone. Although this is where the plot culminates, it does seem to obscure the point of the book. There is no real conclusion – and while this may leave some readers dissatisfied, in a sense it reflects the episodic nature of the rest of the novel, and the reality that there is no neat answer to the problem of alienation in modern life. The ending also ties back to the beginning of the novel in a rather pleasing way.

Like the symptomers, ‘The Cabinet’ is a work that cannot be easily defined, and as Kim puts it, “cold noodles in a bowl for beef broth are not cold noodles … just really poorly made beef broth”, so I’ll take my cue from him and accept that there is no right bowl for this novel. I’ll leave it at this: ‘The Cabinet’ is a patchwork of sad fables and funny vignettes that will appeal to lovers of magic realism, speculative fiction, and reflection in general, but if you’re looking for a straight-forward, Western narrative, this might not be the novel for you.

Éabha Puirséil is a junior at Maynooth University, Ireland, but is currently soaking up the heat of New Orleans as a foreign exchange student. Her hobbies include ranting about the Irish language and admiring the many dogs of Audubon Park.