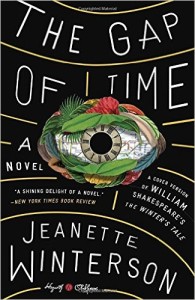

The Gap of Time, by Jeanette Winterson. Hogarth, 2015. $15, 273 pages.

The Gap of Time, Jeanette Winterson’s latest novel, is the first in the Hogarth Shakespeare series, which features “cover” versions of Shakespearean classics. In Winterson’s case, she reimagines A Winter’s Tale, the play famous for the obdurate King Leontes’s accusation of his wife’s infidelity and the ensuing tragedies. While Shakespeare’s works may often lend themselves to homoerotic interpretations, Winterson’s novel opens a queer space that challenges how relationships can be based more on affect rather than on labels. These relationships, moreover, are broken down, formed, and even re-conceptualized by the paths that time allows the characters to explore but only if they are willing to accept that the significations of the past may remain open like the future.

Leo and Xeno (oringally Leontes and Polixenes) have a fraught relationship; however, Winterson tugs at the strings of their friendship when she delves into their past. When they are teenagers, the two boys have a sexual relationship, characterized by not only secrecy to the rest of the world but also secrecy to themselves. They attempt to deny their feelings for one another, and possibly, Xeno’s adolescent accident may not appear as accidental despite Leo’s grief over his suffering friend.

Leo, a proud member of the “one percent,” seems to have everything he could want—a renowned wife, a son (an heir), and a friend who helps him make more money—yet his madness takes over. Winterson integrates modern technology to emphasize that madness. Leo has hidden cameras installed so that he may see whether his wife, Mimi, and Xeno are having an affair; unfortunately, the sound does not work. Regardless of what he observes, which may be peculiar but not necessarily adulterous, Leo chooses to see what he wants to see. In a prescient moment, Xeno says to Pauline, Leo’s assistant and attempted voice of reason, “We’re all unstable. Leo is like a cartoon of somebody who’s unstable, that’s all.” However, Pauline responds, “Leo is like a cartoon of somebody who’s unstable who turns out to be himself.” This scene illustrates Leo will refuse to find any evidence that would dispute his belief in his wife and friend’s betrayal. As a man used to having his way, his belief is his reality. Because of Leo’s rage, he destroys almost all of his relationships: his wife leaves him and becomes a recluse; Xeno leaves the country in fear for his life; Leo and Mimi’s son Milo dies; and Leo rejects Perdita.

Notably, Winterson keeps Peridta’s name rather than modernizing it to underscore her lost-ness across space, time, and even literature itself. Yet Perdita is found by Shep and his son, who take care of her when Shep discovers her in a “baby hatch,” or drop-off, at a hospital. He discovers the baby after he has recently lost his wife, so he takes this child and raises her as his own. This interracial family shows that love can be found in unlikely places and that Perdita is a daughter not by blood or official adoption procedures but rather the emotional bond that she forms with her new father and brother.

Winterson may have tender moments and tragedies but manages to keep her usual wit. When one of Leo’s security guards realizes that Leo has lost his mind, he states, “The fucking fuckers fucked.” With the sharpest barbs, the scene continues with: “[T]his was a perfectly good sentence—adjective, noun, verb. Not Shakespeare certainly, but adequate.” Such scenes point out that Winterson does not want her audience to forget her mission—to reimagine Shakespeare’s work and his careful attention to diction. Yes, she may be filthy, but the tongue-in-cheek quality of this prose lightens mood when the audience has to deal with the tragedies that Leo sets in motion and serves as a reminder that A Winter’s Tale does not fit neatly into the comedy or tragedy genre but rather comprises elements of both.

As with A Winter’s Tale and much of her own oeuvre in fact, Winterson’s focus is to hone in on how time affects all of us. The past, present, and future do not have to be as far apart as we make them out to be. Leo’s decision to crush his relationships has far-reaching consequences, but he still has a choice when he is given a second chance at the end: “Would he smash the moment into pieces or let it open into time?” Opening himself up and reinventing his relationships with his family and friends (if the two can really be that separate by this point) remains an option. Like Leo, we can choose to destroy those around us and ourselves, or we can reconfigure everything—the betrayal, the secrecy, and the death—so that we may become masters rather than victims of time.