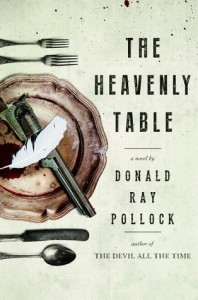

The Heavenly Table, by Donald Ray Pollock. Doubleday, 2016. $28, 365 pages.

Donald Ray Pollock’s second novel, The Heavenly Table, delivers a jolt of the barbed wire and broken toothed countryside mayhem that readers familiar with his debut novel, The Devil All the Time, and his short story collection, Knockemstiff have come to expect. Pollock douses every page of this novel with kerosene and moonshine as he traces the fated trajectory of Pearl Jewett’s three sons, who move from raggedy sharecroppers to accidental murderers, eventually becoming bank robbers and unlikely outlaws. As Pollock details the Jewett boys’ rise from poverty to infamy, he paints a dark pastoral triptych of the Georgia, Alabama, and Southeastern Ohio landscape during the First World War. Like his crime fiction writing contemporaries, Daniel Woodrell, Frank Bill, and Ace Atkins, Donald Ray Pollock arms his characters with grievance, doom, and brutality, as he investigates the violence that is endemic to American culture of any period. Pollock’s portrayal of rustic America during the transitions and upheavals of the early twentieth century provides an interesting analog to the turmoil and anxieties of suburban and urban America in the early twenty-first century.

Historical and social change provides the ominously jittery subtext for the world of The Heavenly Table. Toward the end of the novel, two old men in a general store briefly discuss the merits of having a telephone in every home. Similarly, one of the novel’s most richly drawn minor characters, Jasper Cone, the sanitation inspector in Meade, Ohio, dreams of universal indoor plumbing replacing the many outhouses he is charged with monitoring. Another compellingly drawn character, Lieutenant Vincent Bouvard, struggles with his homosexuality and against the mores of the era. Pollock shows us a world that is transitioning from the horse and buggy to the automobile. The age of mass communication has begun with the burgeoning of the radio and the motion picture. This America at war, with its anti-German xenophobia, eerily echoes our own America of 2016, as it undergoes its technological and societal revolutions; although many of the country roads Pollock’s characters travel down have turned from mud to asphalt, the grotesqueries that lurk behind the woodpiles and lurch from the boondock hollers remain as present as ever. (Look no further than the Trump campaign).

In addition to providing new insight into the recent climate of American disquiet, The Heavenly Table is the definitive rural noir Don Quixote, following as it does, the Jewett brothers’ adventures, inspired by the dime store novel they reread obsessively, The Life and Times of Bloody Bill Bucket. The unnamed narrator of the novel describes the eldest brother, Cane’s, thoughts on the pulp tome that he and his brothers, Cob and Chimney, venerate:

How many times, he wondered, had he read that book to his brothers? He had lost track, but it had to be fifteen, maybe twenty. Though he had always known it was just an outlandish tale written by someone (and maybe Charles Foster Winthrop III wasn’t even his real name) who probably didn’t know any more about killing people and robbing banks than an old maid who’d spent all her life hidden away in a bedroom in her father’s house, it had still given them hope when there was none, something to aim for that was bigger than the life they’d been handed, even if it was crazy to think they’d ever get away with it. And where would they be right now if they’d never found it in that moldy-ass carpetbag? Or, for that matter, if he hadn’t been able to read.

Despite the fact that Donald Ray Pollock has yet again masterfully and mercilessly created a fictional world contingent upon cruelty and utter malice, the written word remains an implicit source of hopefulness for the Jewett brothers, and for the author himself. As Pollock narrates, again, through the thoughts of Cane Jewett: “There were few things in the world that put all people, regardless of education or wealth or place in society, on equal footing, but heartache was one of them.” The Heavenly Table stitches together heartache, loneliness, and malevolence in order that we might touch the seams of our own humanity and have the courage to feel the saving grace that comes from simple human connection. Donald Ray Pollock is one of the foremost novelists charting the bleak in our lack and encouraging us to look for the ordinary digressions of sunlight that might give us the confidence to carry on.

Dante Di Stefano’s collection of poetry, Love is a Stone Endlessly in Flight, is forthcoming from Brighthorse Books. His poetry, essays, and reviews have appeared in Brilliant Corners, Iron Horse Literary Review, The Los Angeles Review, The New Orleans Review, Obsidian, Prairie Schooner, Shenandoah, The Writer’s Chronicle, and elsewhere. Most recently, he is the winner of the Red Hen Press Poetry Award and The Crab Orchard Review’s Special Issue Feature Award in Poetry.