Lamy, New Mexico, 1920

It was so early in the morning that the light could hardly be called light, and an unseasonable frost lay over the ground like a warning. Hector Olivares, esq, sat in his automobile, holding tightly to the steering wheel, reciting Hail Marys without much hope of intercession. He was a small, handsome man, with fine features and a thick head of black hair that he wore slicked back with brilliantine. He wore a fastidious black suit and a high white collar and he shivered in the cold and also with exhaustion. He had not slept, even before the telegram had come at two in the morning, and then he had driven the treacherous road to Lamy in the moonlight, reciting the rosary not for himself, but for that poor girl, Meredith known as Merry, giving birth alone on a train under God knew what eyes. He imagined the narrow paneled train corridor, and strangers in their nightclothes, crowded together, looking down, and then he stopped himself from allowing himself to peer over their shoulders at the girl on the floor. He did not want to see. Yet his filthy mind kept edging toward the group he imagined. The Lord is with thee, the Lord is with thee, the Lord is with thee: his prayers took on the rhythms of a train, and he could not find release from his thoughts. He saw the people crowded around her clearly, as if he approached them with the tracks under him, the train rocking his footing, so that he teetered away from his better nature. But he had been teetering since yesterday, since first he’d seen her.

The station was completely dark, and the door solidly locked, as if to emphasize these untoward circumstances. So Mr. Olivares sat in the automobile, in the dawn, thinking of the poor girl—mother now, Mrs. Smith—Meredith, he could not help but think of her. He thought of her as he had first seen her, a scant day before, when he had been sent by his employers to fetch her: Meredith Rebecca Carmichael Smith, his employer’s niece. Her parents were sending her to give birth out of wedlock.

Her parents had concocted a story: the mountain air, she was always so sickly. In truth, New Mexico had long been the land of misfits and leftover offspring, and it was a fine place for a ruined daughter. They had also invented a husband for her. She is headstrong, her father had written. I cannot emphasize this enough. Further, she is flighty. I trust you will be steady and clear-headed in your purpose. His purpose, he thought with some bitterness, was to act as nursemaid. So often he was dispatched on matters unrelated to the law, though he had struggled mightily to achieve his ascension to The Bar.

Only 36 hours earlier, she’d stood on these same depot steps, in a pink dress, in bright sun, and the light shone through the delicate fabric of her dress and he could clearly discern the outlines of her legs and the swell of her belly, its roundness between her impossibly slender hips. He had not intended to see any of that.

She’d glared at him as if he had personally turned up the sunlight. “Goddammit,” she said. “I’m blinded!”

Mr. Olivares swallowed his shock. “It is prudent,” he told her, “When in New Mexico, to carry an umbrella.”

She looked up at the clear, ferociously blue sky. “You’re completely dotty.”

“Against the sun,” he said. “Especially for one as delicate as you. And then, also, against the rain.”

“Rain,” she said.

“We have thunderstorms.”

“Dotty!” she said, gaily, and this may have been when something teetered in him. When the unsteadiness inside him had revealed itself.

“Grand thunderstorms. At times, the water falls so hard and fast that we have flash floods. Whole flocks of sheep, wagons, have been swept away.” And people, he thought, but did not say. There was no need to frighten her. Already, he felt protective of her gaiety, her airy lightness.

She laughed. She ran her fingers, certain and quick, through her glossy hair, cut shorter than he had ever seen. She had bright hair, blond and straight, and shot with red that in the sun glimmered with the iridescent flash of a bird’s wing. Though the child grew within her, she was as graceful; she moved as if her belly were filled with air. Her eyes were unusually shaped, large and tilted at the corners. She had drawn black lines around them, and Mr. Olivares didn’t know what to make of this.

“Banished!” she said, as if the word pleased and horrified her both. “To this godforsaken place.” She looked around as if she smelled something offensive. “It makes me want to bathe, just looking at it.”

God has not forsaken us, he thought. “It is, truly an unfamiliar place for you,” he said. “I do hope the air proves efficacious in improving your health.”

She said, “Oh, it will. In about a month it will!”

He would not have been more surprised if she had dropped her drawers. He set to cranking the engine to allow himself recovery. It would be a very long drive, and yet he felt no dread. She was like the train, he thought, for the first but not the only time. She was worth watching. Who knew where she might go? She was limited only by oceans.

He was half in love with her before he succeeded in cranking the engine.

***

Mr. Olivares directed the automobile down the dirt road, and she said, “Mr. Olivares, I do believe you’re spiriting me away to the wilderness.” The road stretched onward, endlessly onward, through the rolling piñon hills. “Good God,” she said, “It’s as if all color has been drained from this country.” She told him that everything was gray: the gray green bushes that passed for trees, the gray-blue scrubs that passed for bushes, and he looked at the land and saw it as she did, the sparse water-starved clumps, the bare earth, dry and dirty. A horrid not-color, she called it. “There is no name for that color except dirt.” She rested her head on her hand. “Goddammit,” she sighed. “What I wouldn’t do for a cigarette. Only now they make me sick.”

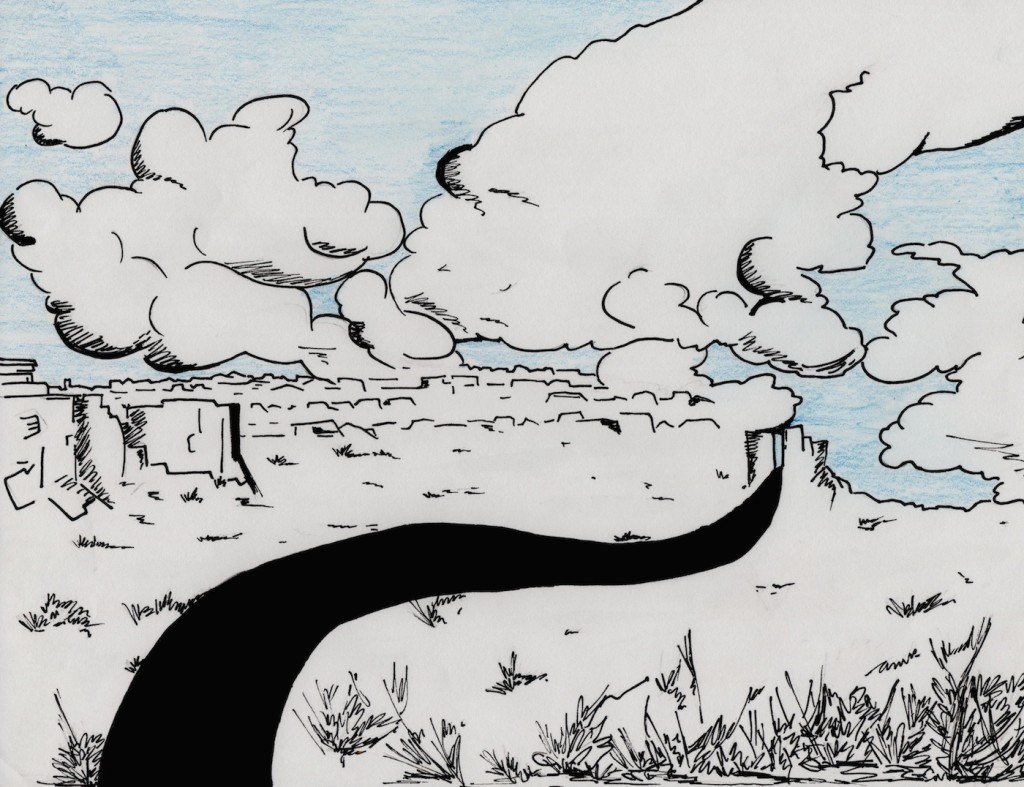

He did not see the colorless world she described. He saw the earth, faintly pink, the deep green of the junipers, the pellucid blue of the sky, the brilliant, glowing white tops of the thunderheads rising on the distance horizon, their swollen bellies the color of steel.

On the long drive she amused herself by trying to shock him. She told him her philosophy of life. She told him things for which she should be ashamed, but she described them gaily, as if there were no shame in them. The story of her embarrassment, her lover with his long fingers. The panels she’d had the girl sew into her dresses to keep her belly from showing. She said that the beast inside her was parasitic, had taken over her body to such an extent that she felt trapped, as if the thing contained her and not the other way around. Well, there was nothing to be done about it now, she said, but once it was out, she was done. They expected her to feed it, like a cow! No, it was on its own. It was a wet nurse for the whelp, she could promise him that. She would be off dancing the Charleston on a table, thank you very much. Her breasts were meant for better things, so there.

He struggled for responses until he understood she didn’t require them. She only noticed him at all if he showed his astonishment, and so he rescued his dignity by failing to be astonished. Impossibly, he understood. He also had found his life seized and maneuvered by another, his employer, who sent him to buy horses and plots of land, who commanded him to fetch children from trains, to arrange nefarious transfers of land and to engineer the release of criminals from the stockade, to collect cases of illegal wine shipped via Mexico as if his sworn duty to uphold the law were as heartfelt as a child reciting the Catechism, memorized but without meaning. And as he listened to her, as he watched her graceful fingers trace the stories of her wild freedom, the teetering within him worsened, but he was mesmerized, entranced; he was filled with a longing to rebel so great that it was all he could do to keep himself from shouting.

Later, she fell silent, and she sighed, a sound so fulsome and heartfelt that he glanced over. She was curled against the door, sleeping. Asleep, she looked like the child she was. Her nose sunburned. Her feet tucked under her skirt. Her lipstick smeared where she rested her face on her arm. He pondered the Maker who organized the world in such a fashion. Meredith was everything his employer had said she was. Monstrously selfish. Vain. Cruel and so arrogantly contemptuous of the opinions of others that she could make a priest doubt God. But she was also a child. A child, he thought, and he who likely would have none in his lifetime felt a confusing tenderness, so at odds with the lust he had earlier felt that he began to wonder if he was quite mad. And when she announced, “This thing is dancing the can-can on my bladder. You must stop before I wet your seat,” he pulled to a stop, and while she went into the bushes he paced the middle of the road and what dutiful angel there was in him swooned, and then he felt himself fall.

***

There were mysteries in the world beyond Mr. Olivares’s comprehension. That a scrap of metal fell from the sky, bearing people to the earth as if heaven itself were throwing them back. That a train, a machine so vast it could stand solid against a flash flood, could fly so swiftly over continents. That his own mother could refuse him praise as if sending a plate of sweets from the table. That he had not managed to produce a family of his own. That Hector Olivares, he of single-minded determination, a man who’d hauled himself up from landless poverty to the heights of The Bar, could teeter so immediately from his perch at the first sight of a frivolous, vain, foul-mouthed sinner, and then could fall so completely that he risked everything to give her what she wanted.

He let her go. Or rather, he failed to stop her. Or rather, he turned the automobile around and returned her to the station, and then he lied to his employer; telegraphing: Not on Train. Please advise.

It was not for him to ask why. He had done it. But ask he did, and he attempted with the hubris of a fool to answer. Because she was so young? Just fifteen, with the soft cheeks of a child, despite her bravado. Because she was beautiful? Because he was twenty-eight, and a virgin, and when he’d turned the automobile around she’d taken his hand and kissed his palm as they were lovers off to elope? Because he was a good Catholic boy raised by a widowed mother as devout and furious as she was fat; who’d raised him on a Catechism of her own, that he came from aristocracy, that he was descended from the first Patrón of their village, Don Diego de Los Luceros himself, and he should never forget it, and the land around them was rightfully his, and he must find a way to get it back; would he rise to this legacy, this holy duty? Would he do as she expected, as she knew he was capable, or would he embarrass her and his dead father and himself in the eyes of God and all his ancestors back and back to Don Diego himself? Yes, yes, yes, he answered, and like the train he had barreled through his life, onward, onward, upward, onward, until the moment when he’d ceased his pacing and looked out at the broad expanse of the Santa Fe basin, and the view that stretched for a hundred miles, the thunderheads rising and the rain falling in great smears of steel, and it was as if he had entered some rare and beautiful kingdom, a land of refusal and assertion, where the language consisted of single word and that word was no.

He had fallen. It was not his to ask why, but only to know that he had.

In the hours since he’d left Meredith at the station, he had mourned himself as if he had died. He’d moved as a ghost through the daylight, and at night sat in his modest, well-appointed sitting room on his handsome needlepointed settee with a brandy in his hand undrunk, waiting for the final judgment which he knew was soon to come, and so certain was he of his demise that when the knock came at 2:34 am, he did not start in fear, but sighed, already resigned, and set his full drink under the lamp where it glowed. He was only surprised that it wasn’t the devil himself on his doorstep, come to collect. Rather, it was a boy, bleary with dreams, resentfully thrusting the telegraph at him, and resentfully accepting the coin he offered

It read, in its entirety: Meet them in Lamy.

So he was here, waiting, reciting the rosary and thinking Them, knowing this meant that Meredith had given birth to her child.

***

The train signaled its arrival, its approaching wail startling him mightily. It squealed to a halt, and stood breathing steam, quivering with the longing to spring forward. This was a flight of fancy, but Mr. Olivares had a romantic streak when it came to trains. For him, they were beasts, puffing and snorting in their need to move ahead. They never reversed, and he loved them for this, though the mysteries of their operation escaped him, and some backwards, superstitious remainder of his brain held that they were the work of the devil.

He alighted from the car and went around the side of the station and waited because he had no idea what else to do. The train door opened and the conductor stepped down, carrying a picnic basket as if he were delivering a lunch to Mr. Olivares, and he held it out as if he hoped Mr. Olivares would be complicit in the falsehood, as if Mr. Olivares would inquire if he had packed pickled olives and perhaps some cheese, and had he remembered the silver? Its two lids were folded back, and someone had at least tucked a pillow inside on which the infant lay, wrapped in what appeared to be table linens. Mr. Olivares accepted the basket and hooked the handle over his elbow, this exchange accomplished in silence.

The mother, Mrs. Smith—Meredith, as again he could not help himself—was nowhere to be seen. The stationmaster saw him searching and spoke as if Mr. Olivares repulsed him. “Speakensee English?” he said.

There was blood on the linens. The child, Mr. Olivares saw, had blood on its face and in its whorls of hair where it had dried into a crust. He said, “You couldn’t bathe it, at the very least?”

The man looked pained. “You have a car?” he asked.

“Cretin,” Mr. Olivares said. The child was sleeping but he worried the air was too cold, and he would have covered it with his coat if not for the fact that he would have to put down the basket to do so. He was seized by the conviction that if he put the child down this man would smash his boot into the basket, the way one would crush an insect.

“You’ll have to open the door,” the man said. And then Mr. Olivares saw another man stepping off the train, carrying a bundle. It was Meredith. They delivered her to him wrapped in a train rug, a blanket heavy and much washed and so ill suited to her that he wanted to protest on the spot for the incivility of it. But he had to tend to her.

He could hardly speak as they thrust Meredith into his arms as if she were already dead. He said, “Mrs. Smith?” But Meredith’s eyes were closed and she did not stir. He was not a tall man and not an athletic man, and her weight, though slight, was a struggle for him, and he feared for the infant in the basket hooked over his arm.

Bearing both of them, he staggered around the side of the depot and to the car. By the time he reached it, he trembled with anger and fatigue both. He turned on the conductor with threats about her father’s wealth, about having the man’s job, which to his own ears sounded like the bluster of an impotent man. “At the very least,” Mr. Olivares said, “at the very least, fetch her some pillows to make her more comfortable.”

The conductor looked as if he would protest, but Hector Olivares, who had made a life out of his capacity for dignity, offered up a monumental, dignified rage, and the conductor retreated when he might have advanced, with his assistant scurrying after him, as if the pillows would be too much weight for one man alone.

Then there was the question of how to open the door, and Mr. Olivares braced his shoulder on the side of the car and groped with his fingertips and managed to get it open. Meredith, jostled as she was by this maneuver, did not awaken. He laid her across the seat and then he could not avoid the image; it came at him with force, the picture of her on the floor of the train with her legs spread, the blood pouring out of the place that had radiated light as she had stood that first time, on the steps of the station and cried out to him, Goddammit! As if she held God Himself personally responsible, as if he, Hector, had something in common with God.

***

The conductor and the porter returned with pillows, and Mr. Olivares arranged them around Meredith and put the baby in its basket on the front floor of the car, and then it occurred to him that he had no idea if it was a little girl or a little boy. “Mrs. Smith?” he said, but her eyes were closed and she lay as if dead. “Is it a boy or a girl?” But she had no answer for him, and he wondered if it were possible she didn’t know, even if she were to awaken.

There was no luggage; it seemed it had gone on to Chicago while they had deposited her on a train returning to New Mexico, and so Hector Olivares started the car and steered it toward the west, with the sun rising behind him and casting the automobile’s own shadow before it.

From time to time, Mr. Olivares glanced at the infant sleeping in its basket. Its sharp chin and its nose both seemed to be creased to a point. Even its forehead had a line down its center, as if the entire head had been folded in half from crown to chin. Mr. Olivares, returning his attention to the road, was seized by the conviction that the child was a girl. He could not be certain why he believed this, except that it was the saddest outcome, for the child seemed especially ugly to him, and for a boy this was less of a disaster. He didn’t like to think in such terms, but even a fool, even that man at the train station, could have told at a glance that this little creature, so fresh into the world, would not have an easy time of it. Perhaps, he thought, having arrived at the narrow trestle-bridge that required more of his attention than he was giving it, maybe her ugliness is an illusion spun by the blood. Even a newborn could not look beautiful encrusted with the stuff of death.

The infant was good, anyway. She was so quiet and peaceful that he tried to catch a glimpse of her chest rising and falling, and then he had to know if it was a girl. If he cared this much for the life of the child, surely he must address it properly.

But soon as he pulled the car to a stop her eyes flew open and her face split into a wide reedy cry of a pitiful beast, and he thought his heart would break. He put her basket up on the seat beside him, and glanced back to where Meredith lay on her bank of pillows with her eyes closed, and the cry rose and grew and filled the car with its unbearable sound. He realized that there was only one way to know the child’s sex, and the act of it seemed so impossibly vulgar and presumptuous that he couldn’t bring himself to do so. He steered the car back onto the road, and within a few moments, the child was asleep again. It was the motion that soothed her.

***

Eventually, in Santa Fe when he stopped for gasoline, Meredith opened her eyes. He tried to offer her water or food, but she would not answer him. He wasn’t even sure if she saw him. She looked past him, out the car window, and would not meet his eyes though he maneuvered himself in front of her face, trying to catch her gaze. He thought if he could just make her look at him, he might be able to bring her back to the world, but she evaded him.

He did not know what to do, and he said to her that he was taking her to her uncle as originally planned, and this alone seemed to arouse her. She said, “No.” He wasn’t sure he had heard correctly, but she repeated herself, and even in her damaged state her characteristic petulance crept into her voice. “No,” she said again.

In the canyon, just past Riconada, the automobile overheated and Mr. Olivares pulled to the shoulder. The child’s wail was worse than before, but Meredith lay on her pillows unmoved, gazing out the window with sightless eyes so that for an instant he entertained the idea that she had been not only blinded but deafened by the delivery.

He ran down to the river with the bucket he carried in the trunk for such occasions, and he ran back to the car, sloshing water on his fine wool suit, and then there was nothing to do but wait for the radiator to cool sufficiently for him to open the cap.

The baby wailed. The mother stared out the window and did not stir, and he said, “I beg. . . I beg your pardon. . . I beg,” and he might as well have been pleading with the infant as with the mother. In desperation he lifted the baby from the basket and for the time it took him to lift her she paused, her eyes fixed on him as if he held all possibility in the world, but when he laid her against his chest she began to cry. “I beg,” he whispered, and then he climbed out of the car with the child who again stopped crying and he paced alongside the Rio Grande, and as long as he moved the baby was soothed.

He wondered what it would do to the child if he dipped his handkerchief into the water and let her suck on it. Hours had passed and he thought that the baby must have been starving.

Beside him, the river, the mighty Rio Grande, was swollen with spring, and he saw it anew, a narrow brown runoff, scummy with the force of its current, studded with boulders, bordered with weeds. He realized that this was a stream, a creek, a gesture toward a river. It was a placeholder for the river the land needed. The cramped narrowness of his own life compared, and he thought of the rivers he had not seen, the Mississippi, the Themes, the Seine, the Amazon, and a wash of sorrow and fury ran through him.

The walls of the canyon rose up around Hector and the infant, the darkly purple rock, and the sky was a slice of blue. The baby’s eyes fixed on that blue as if she saw something there. He carried the baby down to the water, and he dipped his fingers in the current, and as he did so an image came to him so bright and shining that it was like a vision, and in this vision the baby slipped from his arms and fell into the water. Horrified, he clutched her to his chest. This made her cry and he pressed his thumb to her lips and she accepted it and sucked fiercely but this seemed to drive her to greater screams, and he returned to the car and opened the back door and said, “Goddamit, woman. For Christ’s sake!”

Meredith looked up with startled eyes, and he saw how two wet stains had formed on the front of her nightgown, and he knew without question that he was beyond anything he could understand, and what he did next, he did for the child in his arms.

Mr. Olivares’s fingers trembled as he put them to the buttons that ran down between the two wet circles. Meredith looked at him but did not see him, and she smiled faintly, the tender smile he imagined she offered a lover, but he was not aroused; it was not for him. It was only like helping his father with the lambing—he dimly remembered this from when he was very small, the lamb and the ewe and the teat—“Sometimes the first time she doesn’t know what to do,” his father had said to him. “You have to show her how.”

He could not unfasten the buttons with one hand, and he put the baby down in the nest of pillows beside Meredith, and this that made her speak, as if only then did she understand what he intended. “No,” she said, her face suffused with a dumbfounded, childlike fury. She stirred, the weakest of struggles, and the baby screamed. “Absolutely not,” said Meredith, and she tried to rise, but he put his hand on her shoulder and pressed her back. “Be still,” he said. He crouched awkwardly, half-perched on the running board, and his fingers trembled but with these trembling fingers he slipped the top button free, and then another and another, and when he had done this enough times he folded back the cloth and bared her skin and then her breast to the light of day. He did not want to look but he did. Her breast was swollen, and traced with veins; he could see the whole anatomy of her veins, the larger vessels branching smaller and smaller and there the nipple, pink and hardened to the air and the sun, glistening with a clear liquid that seeped from it, and Meredith whispered, “No.” Her gaze at last fixed on his eyes and tears welled in her eyes and she said, “No,” pleading now, not refusing at all, but asking, and in that moment the enormous flexibility of the word revealed itself to him. A request, a refusal, a longing, a sorrow, a trap. The word was all of these and more.

He didn’t know how to proceed anyway, but then the baby did the most astonishing thing—he could not have been more surprised if a deaf man had risen and sung an aria—the baby moved and squirmed and struggled free of her napkins and tablecloth, her mouth opened wide, and those eyes that had stared so intently at the sky now turned to her mother’s breast, and Meredith whispered, “No,” and he held her shoulder down again, and the baby wriggled until close enough, and then her mouth closed on the nipple, and Meredith went away again. She looked past his shoulder as if he was not there; she looked to the sky and she wept. He watched the tears rise and pool and spill without a trace of sympathy in him, and he wondered if one could only feel sympathy for the mother or the child but never both.

Later, even years later, he would lie in bed and be unable to keep the memory at bay. He would remember opening Meredith’s blouse, his hand on her shoulder forcing her down, and her pink nipple hardening in the sunlight, and he would feel as if he had molested her, ruined her, even raped her, and in his memory it was as if the child hadn’t been present at all.

Goldberry Long is the author of the novel Juniper Tree Burning. Her novel Miss O’Keeffe’s Lover is forthcoming from Simon and Schuster. She lives in California with her family, where she teaches fiction writing at the University of California-Riverside.

Illustration by Katherine Villeneuve