Muscular, hairy, and naked to a fault, the man and the woman gazed at one another with the dead, painted eyes of storefront mannequins. If this was love, and nobody could say otherwise with any certainty, then it was onanistic love; the man and woman were near identical in features. Both stood with the wide stance of a lacrosse player; both had the pigmentation of a recently lacquered dining table; both had unrealistically perfect teeth. At their feet a plastic illuminated sculpture, humming with an internal light bulb, gave off only imaginary heat. What passed for mood lighting caused the deep black lines of the man and woman’s matching abs to deepen even further, so that the pair seemed to be more heroic than what their nudity allowed: they could be superheroes without costumes, sculpted celebrities without groomers. Hair was coming from places where no hair does—on most humans, at least, sprouting over the terrain of their bodies like a woolly moss. The man and the woman, naked as the pre-historical day they were born, were hirsute, feral placeholders of the first man and woman, and as such were alone in the single planar museum set of the newest wing of the Tokyo National Museum of History and Science.

Since this was an unfinished display, there were no information placards to offer contextual explanation: why this full-scale diorama was down the hall from the needled-down butterflies, why it was next to an underwater scene of coelacanth. The museum’s only two visitors, both young boys, looked at the glass wall separating them from the exposed figures as if it locked them in, as if they themselves were the display. Genichiro Takahashi, the older boy with the rapt, gelled hair, put a small hand on the glass, smudging his fingerprints on the clear divide. This was another instance of adults keeping the knowledge of the sexual universe always at a remove, holding the information above their heads like a bully might to a hapless victim. The other boy, Shoji, diminutive and packed with baby fat, looked from Genichiro Takahashi’s hand to the woman’s breasts, realized that outside of his immediate family, these were the first pair he had ever seen, and he shifted in his Velcro-snapped tennis shoes with an uncomfortable squirm.

“Are those big? They don’t look that big.”

Genichiro Takahashi made a noise halfway between a sigh and a lazy expletive. “Nothing like Yuki’s. She was huge.” Genichiro Takahashi removed his hand to cartoonishly mime his meaning. He continued. “Anyway, the nipples are all wrong. Look at those bumps. I don’t know what that’s supposed to be. That doesn’t look real at all.”

“I brought the soy sauce.” Shoji motioned to his own red backpack. He was trying his hardest to change the subject. “Like you asked.”

“Not right now,” said Genichiro Takahashi.

The boys, one with a tired resolve, the other with obstinate fascination, watched the Neanderthal couple for another ten minutes in complete silence until a security guard with a paunch and a sneer of obvious disdain limped behind them, pretending not to say with his leering what he wanted to say with his asthmatic voice: get a move on, perverts.

And so they finally did.

*

The museum cafeteria, perfumed with cleaning product and katsu, appeared for the most part so sterile as to be medically sound. It was, for a Friday morning, empty—a pruny, aproned woman clenched a facial tick as she sponged down a steel counter, a young mother, visibly tired even under a layer of makeup, urged her son to eat the dinosaur-shaped chicken nuggets before him, and a business suit with broad shoulders and a newspaper casually sipped a bowl of miso alone in the far corner of the room.

Genichiro Takahashi and Shoji, splitting a snack-size bag of seaweed-flavored crackers, sat in the periphery of the suit, toward the rear of the hall, near the jumble of a bussing station. Short, crooked plate-stacks sprinkled with bits of noodle stood like a fetid skyline behind them.

“How long are we going to wait?”

“Keep your voice down,” said Genichiro Takahashi, looking sideways. “Not enough people, not enough noise. The timing has to be perfect, fool-boy.”

“I don’t want the soy sauce to leak in my backpack.” A few wet crumbs fell out of his puckered mouth as he spoke. He wiped them away with the back of his hand. “Can’t I just take it out?”

“Don’t you think that would look pretty stupid? A fat boy with a bottle of soy sauce in his hand?”

With a swimmer’s sigh, Shoji lowered his head until his dark bangs grazed the table.

“What’s the matter with you, idiot-head?” asked Genichiro Takahashi. “Pull it together.”

“I don’t know,” Shoji said, and then felt the chill of tabletop on the blank billboard of his forehead. “Our table is ice cold.”

“You’re an idiot-boy with alarming frequency.”

Under the table, Shoji started tracing his name with his fingertip across his jeans. “What are we going spend the money on?”

“I don’t know,” said Genichiro Takahashi.

Nearby, the man in the business suit folded his newspaper with the swiftness and torpor of a daily habit, stuck in under his arm, and moved out of the cafeteria, his tongue cleaning his front teeth. His stride seemed powered by the invisible force field surrounding him, a humming of wealth and satisfaction. The boys’ stare, glued to the man’s suit jacket like they had never seen clothing before, went altogether unnoticed.

*

They sat in silence, the moderate smorgasbord of syllables and half-sentences a white noise in their background, until Genichiro Takahashi’s eyelids snapped open. His voice turned baritone: “OK, fatty, I’ve made a decision. We’re not going to do the soy sauce thing after all.”

The shock of the news was minimal. Shoji’s shoulders drooped in his oversized sweatshirt, visibly out of relief.

Genichiro Takahashi repeated himself.

“I heard you,” said Shoji. He chewed on the inside of his cheek and then asked the next question of out duty. “How come?”

“There’s too many people in here.” Genichiro Takahashi meant it. Not a stranger to ending a scheme prematurely, usually out of an indeterminate fear, something he mistook for a premonition, Genichiro Takahashi now felt the weight of more than forty pairs of eyes blinking in his direction. The extent to his paranoia included the cafeteria workers in their hairnet helmets.

“Can we go home now?”

“No,” said Genichiro Takahashi, still using the deepest voice a boy under the age of fifteen could muster. “I’ve got a Plan B, dummy.”

*

Plan A had been simple, and, like the most successful of ideas, was plagiarized entirely from the Internet.

Shoji, the less competent of the two, would commit the most common of childhood blunders: he would spill something, in this case soy sauce, on The Mark’s pants.

Shoji would cry and beg forgiveness.

Genichiro Takahashi, sitting at a different table, likely on the opposite side of The Mark, would interrupt with a stack of napkins in an upraised hand.

“I apologize deeply for his fat idiocy,” Genichiro Takahashi would say, and then begin to wipe up the soy sauce puddle from The Mark’s pants—as Shoji’s crying would increase intensity and volume.

The Mark, flustered that an overweight child had just ruined his belongings, would be so distracted with the tears and the wailing that he/she/it wouldn’t notice Genichiro Takahashi slipping his napkin-free hand into a pocket to steal whatever he could.

One person makes the mess—the other, the thief, offers to clean.

Simple.

The complexity of the ruse was in the preparation, namely, choosing The Mark.

Among the recent influx of tourists to the cafeteria, few were potential candidates to be swindled; most were parents or school teachers or otherwise lower-to-middle class visitors, all of whom probably carried a poker hand of credit cards but less than ten thousand yen. The boys were poor, not desperate.

No, their desire to find yen-carrying targets had more to do with the worthlessness of pilfering credit cards, a lesson learned after Endo Tazuko, a sixteen-year-old with a penchant for brandishing a butterfly knife at the drop of a hat, had been sent to juvenile training school after credit purchases were electronically traced to his family’s shabby, kitty-litter-perfumed apartment; Endo Tazuko, it turned out, had tried to buy online pornography using a stolen card. Not exactly an idol of heroism, Endo Tazuko nevertheless was remembered as a caveat of pinching traceable funds.

*

Shoji, in the meantime, having resigned himself to the shorter, kid-sized urinal, examined the wall tile in front of him and the obscene graffiti scrawled across it as he urinated.

A headless, comic-book-proportioned naked woman in blue pen caught his eye first.

Shoji said, “Must be Naked Lady Day,” to no one in particular.

When he was done, he shook, zipped, and flushed, and then washed his hands for 90 seconds just like his mother taught him. Then he un-shouldered his backpack, took out the soy sauce, and tossed it into the trash overflowing with balled up paper towels.

Relief immediately set in: the soy sauce plan was trouble through and through.

Hugging his empty backpack, Shoji felt weightless, as if gravity had rewarded his bottle-into-trash action by offering him a reprieve from physics. He started to float but thought better of it. To settle his breath, he decided then and there to stop at a convenience store on the way home and buy a replacement bottle for his mother. There was work to do and games to be played, so he took one long last look in the streaky mirror above the sink, puffed up his cheeks like a squirrel, laughed at the sight, and feeling satisfied left the bathroom with an excited gallop.

At the elevator, Shoji smelled his own sweat. He pushed the UP button and stuck his hands into his jean pockets. In his left pocket, he felt nothing; in his right, a small scrap of paper.

His pockets had been empty that morning.

It was a note from Genichiro Takahashi, written along the outside border of a torn-in-half 1000 yen bill. He read the message aloud.

“Meet me at Michiko for Cry Baby.”

When the elevator doors slid open, Shoji slunk in, nearly dragging his knuckles on the ground.

*

Past the lobby and the curved desk of ticket sales, past the colorfully rigorous displays in the museum store window, past the preoccupied employee reading a Murakami novel at the coat check, the main hall of the National Museum of Nature and Science was a humbling sight: a cathedral-high ceiling barely tall enough for the single Tyrannosaur skeleton centered underneath it; an expansive, rectangular skylight complicated the lighting of each dinosaur bone so that, with the help of the spotlights, the shadow of the monster’s ribcage criss-crossed like a Go board. The T-Rex was raised on a cement platform to give the illusion that it was full-grown, but “Michiko” was a child, relatively speaking, the most complete teenage Tyrannosaur skeleton in Japan, and if there had been any confusion on the part of museum visitors, a draping black banner proclaimed a somewhat misleading title in yellow letters across it’s feet: TERRIBLE MICHIKO, QUEEN OF THE CRETACEOUS. There was nothing else in the main hall, only signs pointing visitors to other time periods and exhibits.

The hall was Michiko’s, and with the exception of the cafeteria, it held the most people at any given time.

Genichiro Takahashi was already there, a museum map folded out between his hands. He stood on the fringe of a pack of wild school children, younger children than Genichiro Takahashi, their height and iconographic backpacks giving away their single-digit ages.

Watching Genichiro Takahashi feign interest in the adjacent teacher’s discourse on paleontology pushed Shoji’s buttons more than he could communicate. As he came closer to the t-rex, Shoji’s fists clenched white until his fingernails made imprints in his palm.

Why couldn’t Genichiro Takahashi actually learn about dinosaurs? Dinosaurs were awesome.

Not that Shoji considered himself an expert, or, for that matter, intelligent, just interested. It was good to recite words like Archaeopteryx or Jingshanosaurus, to explain the mating rituals of the Pachycephalosaurus to a gawking adult. Genichiro Takahashi didn’t seem to care about anything that wasn’t under the larger header of looking cool, whether that cool meant developing an involved scheme or showing off an impressive if not rather meaningless habit, like rote memorization of license plates.

Genichiro Takahashi made the briefest of glances at Shoji and then furtively swung his line of sight to a broad shouldered man in a striped suit, sitting on a short bench in between them and jotting down notes onto a clipboard. It was the same suit as this morning in the cafeteria. Without a newspaper or a bowl in his hands, the suit gave off a stronger aura of confidence, if that were possible, his chin up and away from his clipboard as if even work were beneath him. The suit tapped a polished, black shoe without rhythm, placed a pen against his cheek, then continued scribbling.

*

Michiko’s skull, roaring in the direction of the front entrance, was colossal despite its lack of maturity, a cranium the size of a park bench. Everything about Michiko was sharp, aggressive; Shoji was convinced that if he even grazed his fingers across the relatively gentler curves of her spine, it would draw blood. With fingernails not dissimilar from those he had seen in nail salon displays, the sight of Michiko’s predatory digits made the lower half of his own body feel detached, separated from his torso. It could have been the adrenaline, or the growling of his stomach, but it felt, in the basement of his heart, like the first time they had met, and Shoji was first-date nervous. To ameliorate the situation, Shoji held out his hand to the space between them.

“I’m Shoji,” he said, brushing his bangs aside. “And you’re Michiko.” He could see a blur of an irritated Genichiro Takahashi out the corner of his eye but ignored it.

Michiko could have said, “I remember you,” but it was hard to hear among the din of sightseers. She did not move to shake hands.

“My friend over there is watching us right now. You’d like Genichiro Takahashi, even though he’s kind of a jerk sometimes.”

Michiko telephatically said, “Looks like a shitty friend.”

“I guess.” Shoji took off his backpack and dragged it on the floor by the arm straps as he moved toward a nearby bench. “He’s a pretty great thief, though. One time he stole a coin from my pocket without me even noticing. It was pretty cool.”

“Still looks shitty.”

Though slightly perturbed by the coarseness of her language, Michiko the T-Rex was turning out to be a good listener. Shoji continued with a hint of regret. “I can’t talk too long. Genichiro Takahashi wants me to start Cry Baby.”

Michiko’s telepathic voice lowered to a whisper. “I love you, Shoji. You’re not fatty.”

“I love you, too.”

With that, Shoji, who was about to sit down, changed his body’s mind at the last second and let his backpack drop on the ground. He took a deep, adult-sized breath, and, fixing his posture, shouted in the best outside voice he could muster:

“Help! Somebody stole my wallet!”

*

That everything fell apart was entirely to be expected.

At Shoji’s allegation of thievery, the National Museum hall went full-steam crazy: witheld breaths, rubber necking, and searching for a mandate were all standard fare. The nearest security guard, the same limping fellow with the paunch from the morning, came toward Shoji with impressive speed, his eyes darting back and forth for an obvious suspect. Schoolteachers worked like shepherds to control their flock in as tight a circle as possible. Others, including The Mark, went straight for their belongings, patting pockets, checking purses, to determine if their valuables were still intact.

Genichiro Takahashi, for whom this shouting had occurred, was already working, as it were, observing The Mark in the suit with a committed gaze. Within an instant, it was confirmed; the suit slipped a hand into an inside jacket pocket to see if his money clip was still there.

Genichiro Takahashi grinned beside himself.

With a grizzled, attention-gathering howl, the same security guard from that morning brought his arms up to signal importance: “Everyone! Please remain calm!” In the next few seconds the room’s voice had lowered by many octaves; people were eager to be told what to do. The guard’s dismay at being in a position of authority crept through in the audible vibration in the old man’s voice. “Check your belongings! Has anyone else been a pickpocket victim?”

Shoji was holding his own. The adults closest to him had placed their hands on his back, were bent over to listen to his gibberish. He was so emotional that few were able to ask him a direct question like, “Who stole you wallet?” or perhaps the more sensible, “Are you sure you didn’t forget it somewhere?” Shoji wailed and used his forearm to wipe his nose.

After a few minutes of enjoying the chaos, Genichiro Takahashi started over towards The Mark, making sure to creep as informally as possible. Shoji had taken to crying in siren bursts, sounding like a faulty car alarm in the middle of the museum. The security guard was trying his best to calm the boy down. It was not working.

A few feet away, the suit had pulled out a cell phone and was speaking into it with a comfortable directness. The man was clearly enjoying his chance to offer a recap of the action.

He finished his phone call with a routine “I love you” and an “Until later,” then snapped his phone shut with a lackadaisical convulsion. He stood up like a three-hour film had ended, arching his back and cricking his neck, and then without the slightest look at Genichiro Takahashi, went directly toward him.

Their bodies connected with the slightest of bumps, more of a push-aside than a direct collision. It was just enough. Genichiro Takahashi scissored the money clip with his first two fingers, touched the adult on his opposite arm as if to say, “Excuse me,” and moved past him with a self-assured boost of kinetic energy.

*

An hour later the baseball-sized spotlights cast a histrionic glow over the two boys as they moved down the empty hall of the basement floor. On either side of them, spiders, beetles the color of oil slicks, and butterflies were pinned behind glass. Shoji, a few steps behind Genichiro Takahashi, looked at the glass cages and prayed for movement: a twitch of a leg, a spasm in an antenna.

Genichiro Takahashi, his head down, counted the money.

“Do you think these bugs were dead when they were pinned?”

Genichiro Takahashi took an absentminded pause from counting. “They’re pinned alive.”

“That’s disgusting,” said Shoji.

“Shut up and let me count.”

The hallway narrowed, or felt as if it had. Shoji stopped abruptly, his hands wrist-deep in his pockets. “I feel sick.”

“No you don’t.”

Shoji wanted to rest his head against the wall, but with the Insect Exhibit wrapping around the corridor, he couldn’t risk easing a forehead against the glass and bringing to life an otherwise dormant spider. He sighed so heavily he probably lost weight, then took to pacing past the display.

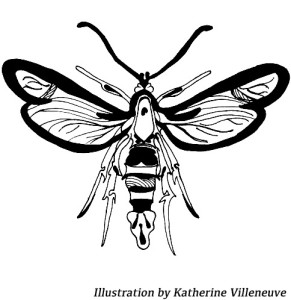

He nearly threw up when he saw the Lesser Peach Tree Borer. It had a pinecone body similar in hue to undercooked pumpkin pie, transparent wings that appeared moist to the touch even after years behind glass, and a locust’s face. Surrounded by colorful butterflies, the Borer seemed a hideous embarrassment, or else a purposeful middle finger to nature.

“Genichiro Takahashi, I think this one just moved.”

“Shut up,” said Genichiro Takahashi, still counting.

Immediately next to the Lesser Borer Shoji saw a cousin species, the Greater Peach Tree Borer, which, though larger, still retained the same gauzy, half-digested look.

“Genichiro Takahashi, this one moved, too.” For a moment Shoji wondered how difficult it would be to break the glass. With a fingernail he tapped the surface. “Very gross.”

“What are you doing?” Genichiro Takahashi’s attention shifted. “Do you want to set off the alarms? Don’t touch anything.”

Shoji shifted his backpack, and looking around at the other insects waited for a flicker of life. He cleared his throat. He waited and listened to the sound of money, of Genichiro Takahashi’s breathing. When nothing moved, the spotlights dimmed. The butterflies lost their color.

After a few minutes, Genichiro Takahashi gave him a fistful of money. “Thirty thousand. Not bad, I guess. This is your cut,” he said, and handed him a thin fold of bills. “We can’t come back here. I mean it.”

Shoji’s chest grew tight. He suddenly felt light-headed.

“Shoji? Idiot? Hello?”

The two locusts flicked their wings.

Shoji knew where to go.

Without warning he left Genichiro Takahashi and bolted down the hall. He ran around a waste basket, pulled around a sharp corner, and sped near the Neanderthal couple. Shoji did not look at their nudity, their campfire, their sad eyes, their hair as he flew past. Had he stopped he would have seen them kissing.

Johnny Day‘s writing has appeared or is forthcoming in Black Warrior Review, Third Coast, Hobart, Indiana Review, and others. He lives and teaches in Portland, Oregon.