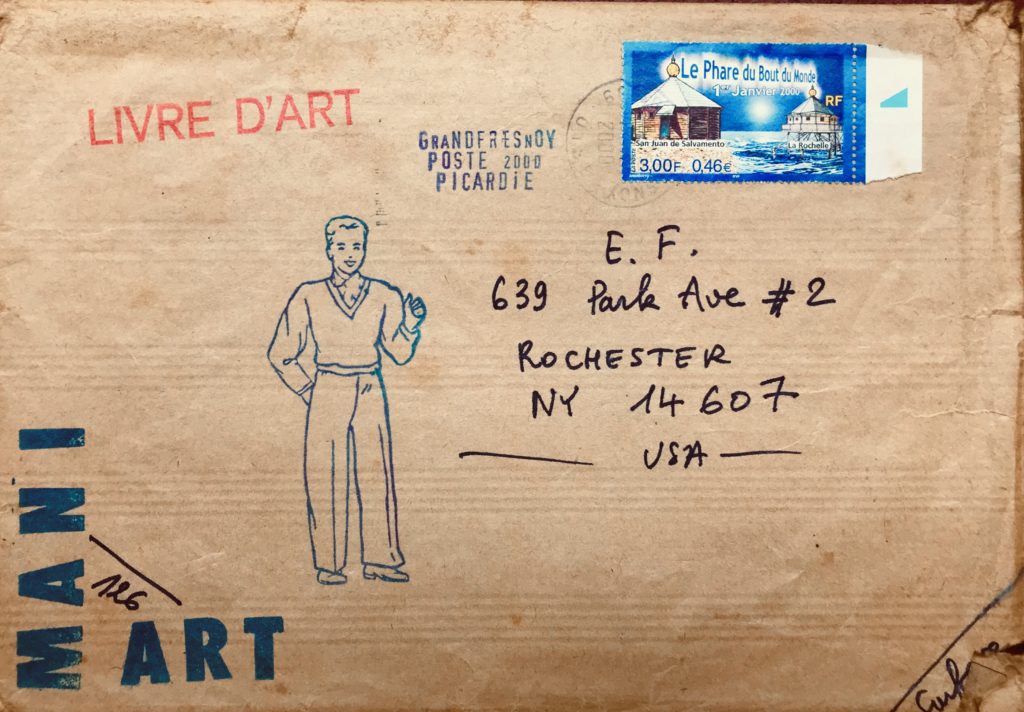

In 1995, the summer after I graduated from college, I received my first envelope from a stranger named Pascal Lenoir. Inside the tan Euro-style C5 envelope was a collection of original artworks varying in size, subject, and texture. Several were collaged and many included text and rubber stampings. This was the curatorial mail art project of Pascal Lenoir. I received my last Mani-Art envelope in 2000, the year I began an MFA program in painting and then I pretty much forgot about mail art until now.

“The postal service is a joke.” President Trump said last April. And as is usually the case with this president and jokes (cue clip of Seth Meyers at The Whitehouse Correspondence Dinner), Trump was not laughing. Trump’s “War on the Postal Service,” which has been going on for some time, now has a chapter called “Mail-in Votes.” At the same time we have the pandemic. We continue to endure various forms of isolation from the initial lockdown and travel restrictions, to work and school life being conducted remotely and the threat of another surge and lockdown. For those involved in art, the pandemic and the strangely politicized topic of the U.S. postal service have converged over recent months. It turns out I was not the only one who found myself recalling mail art.

Last spring, Artnet published an article by Taylor Dafoe titled, “Mail Art, a Quirky Pursuit That Hasn’t Been Popular Since the ’60s, Is Suddenly Having a Renaissance Amid the Worldwide Lockdown.” In April and May Printed Matter in New York put out a call for mail art submissions and mounted a window exhibition. (For anyone wanting a smart, good looking overview of mail art, this page is the place to go.)

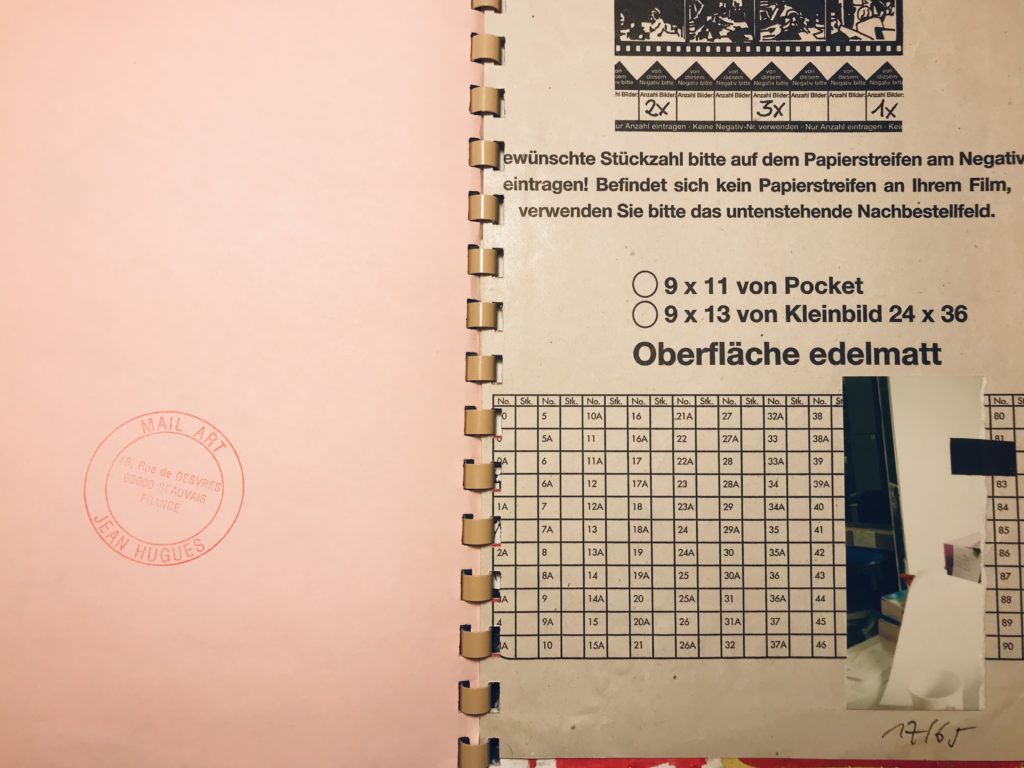

For me, mail art—the aesthetic of it, the idea of it, my participation in it—is lodged in the second half of the 1990s (the era of Griffin and Sabine and Il Postino) and is exemplified by the Mani-Art curated zine project of Pascal Lenoir. Contributors found Pascal Lenoir’s calls for submissions in art classifieds or specific mail art newsletters. They mailed 60 small works, often collages and altered multiples, to Pascal Lenoir in Grandfresnoy, France. Eventually, a distinctive envelope, addressed by hand, handsomely postmarked and adorned with a variety of rubber stamps would arrive for all participants in the mail. Inside was a collection of mail art, comb-bound or sometimes loose. It included a list of the names and addresses of art makers from all over the world. At that time I had not travelled much, and this world-travelled object spoke both to my wanderlust and my tendency to engage with strangers.

Looking through my small collection of mail art, mostly envelopes sent by Pascal Lenoir, is a pleasure—though it is different from the pleasure of looking at a painting in a gallery. The individual works reveal little about their makers and the gesture seems as important as the work itself. Many works of mail art have a dada aesthetic, a played-with surface quality, and the look of something the maker was never too attached to in the first place. Mail art looks best when viewed as a collection rather than individual works of art. My mind wandered from the mail art collection in front of me to Pascal Lenoir himself. So I did what I could not do in 1995: I Googled him.

It seems Pascal Lenoir was still involved in Mail Art as late as 2008 and could be to this day. I think I recognized one of his envelopes on the Printed Matter page. He still lives in Grandfresnoy and at the same address. He is featured in a video posted on Dailymotion and if my basic understanding of French serves me at all, I believe he now publishes an almanac, a collection of stories and drawings from his region in France. In other words, his profile is different than that of a “contemporary artist” and I am pleased by this. I want to have a coffee with this man. I not only like his mannerisms on the video, his projects are generous. On a mail art blog called Mail Artists Index, there is an image of a stamp. It reads: “Mail Art is Not Fine Art It Is The Artist Who Is Fine.” I think this is pretty accurate.

Jess Pinkham, a confessed mail-enthusiast, observed the up-tick of Trump’s aggression toward the postal service from her lockdown in New York City last spring. From that place and moment she began a series of photographs of postal workers, which I have been following on Instagram. There is an obvious resonance with Van Gogh’s paintings of the postman Joseph Roulin. The photographs themselves are appropriately straightforward, unlike lot of Jess Pinham’s photographs, which are beautiful, dramatic, or humorous. But mail is often delivered in high sun or dull light, in ordinary and not picturesque settings. Judging from the empathy in her projects, I also imagine Jess Pinkham not wanting to inconvenience the postal workers or take too much of her subjects’ time. The steadily growing number of photographs gives power this quiet homage to postal workers, their service, and the Institution of the United States Postal Service.

I spoke with Jess Pinkham by phone about the series. On April 21, 2020 she photographed her mail carrier, Hayes, and has since sought out other mail carriers to photograph. She describes them as “essential workers” of the pandemic (and all times) who are often overlooked and under-appreciated. She has no end-goal for this work, no art-career-driven motivation. She always asks for permission to take the photographs and permission to share them on Instagram or elsewhere. She offers to send the subject a digital copy or my mail, a postcard of the image. This series is not what one would call mail art, though Jess Pinkham also engages in what would more traditionally fit this definition. Almost every day since 2012 she makes and sends a postcard to a friend or acquaintance. Then, in 2016, she started a weekly practice of sending fan mail as “an antidote to the trolling epidemic.” Jess Pinkham’s recent photographs of postal workers are a kind of fan mail. When our phone call ended and when my mail was dropped off the next day, I continued to think about the USPS. If the postal service is a joke to Trump, maybe it’s because it belongs to us, we the people—and not to him.

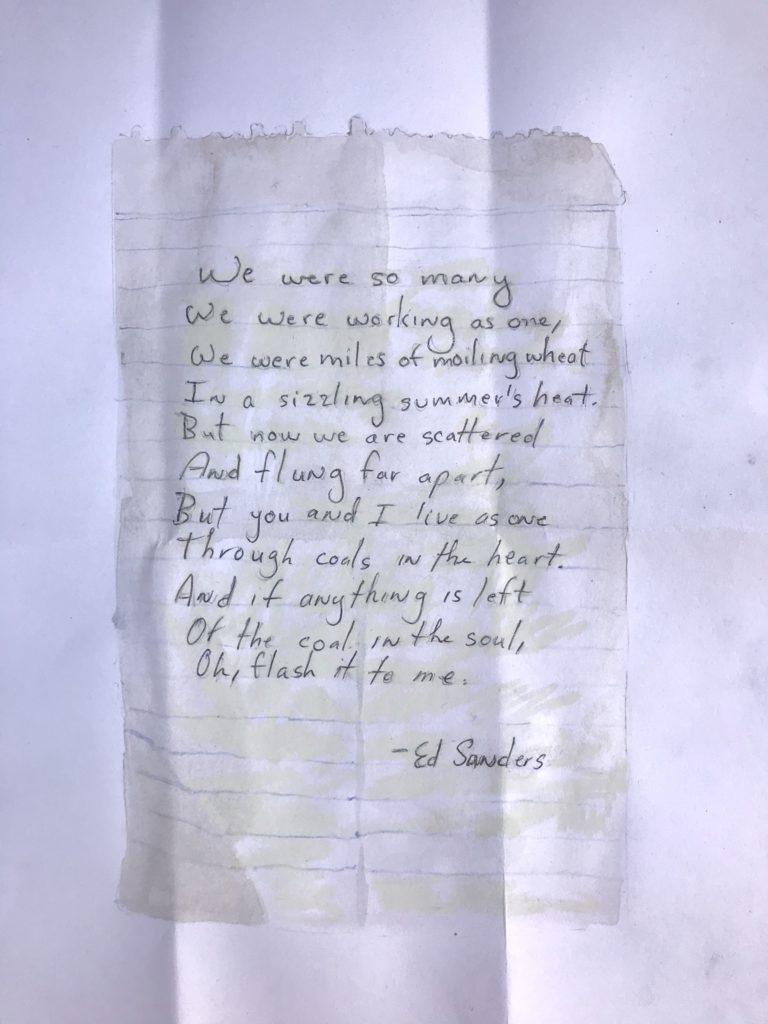

I received a piece of mail about twenty years ago. It was not mail art, though I met the sender when we were both in art school. I had a crush on Michael Dwyer, a pleasant, unrequited friend-crush, which somehow fit right in to the vibe of the 90s. When we left school, my friends and I were dispersed in a world not yet interwebbed by texting, email and social media. An envelope from Michael Dwyer arrived at my parent’s house some months or a year after we had left school. Inside the envelope on small piece of paper from a spiral notebook, were some lines of poetry in Michael’s handwriting. The there was no title but the name Ed Sanders was written below. The last three lines of the poem have stuck with me all these years, and I think of them mostly when nostalgia arises, a sense that we accidentally left something in the past, something we could use about now:

And if anything is left

Of the coal in the soul,

Oh, flash it to me.

I lost touch with Michael Dwyer and quit Facebook a long time ago. So I Googled his inconveniently common name and the last place I knew him to live. Finally, I found a picture of the face I still recognized, affiliated with some big company in a major American city. In his company photo he is wearing a suit and tie and I thought about how far and fast time carries us from where we were. I thought of sending Michael a photocopy of his note, now a relic, but could find no current email or physical mailing address. I made a drawing of the note, carefully copying Michael’s handwriting and the yellow of the aged paper. And then I made three more drawings of it. I mailed one to Pascal Lenoir in France, one to Jess Pinkham, and one to Ed Sanders who is 81 years old and lives in Woodstock, NY. The last drawing I saved for Michael, just in case I find his address one day. It’s not fine art but it feels like a fine gesture.

Images in order of appearance: Mani-Art Envelope from Pascal Lenoir, 2000, Page from Mani-Art Issue 126, 2000, Photographs of Postal Workers by Jess Pinkham, Drawing of a letter from Michael Dwyer.

Emily Farranto is a writer and artist. She started the art blog Village Disco in 2015 and her children’s book, Animals Mate, was published in July 2020.