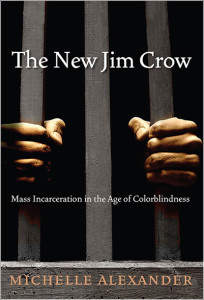

The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, by Michelle Alexander. The New Press, 2010. $19.95, 336 pages.

{Michelle Alexander will present her work at an event beginning at 6 p.m. on Wednesday, Oct. 2, in Dixon Hall on Tulane University’s Campus. More on the event here.}

The New Jim Crow has captivated many Americans’ attention since it was published in 2010. Michelle Alexander has become the poster woman for ending the drug war and mass incarceration, for policy reform and for mass movement organizing. She wrote this book for liberals like her to alert them that this system—in which people are being targeted, criminalized, stereotyped to support popular complacent consent for criminalization, incarcerated, and then denied full citizenship upon release—is a legacy to the racial caste system that was Jim Crow. While this I believe to be true, I also believe that there is more to unfold in the story than Alexander has presented in her book.

The New Jim Crow has become, to some, the seminal reading on the current state of American incarceration and how it got that way. It has been a ringing alarm for some who could have gone their whole lives and never known about the way that the war on drugs has disproportionately affected certain vulnerable segments of the population and made others vulnerable that may have not otherwise been. She has highlighted the transformation from Jim Crow segregation to a more subtle system, backed up by notions of public safety and allegedly operating according to a dictum of colorblindness. The rapid fire of a lynching has been turned over to the slow crock pot cookery of the criminal justice system that titillates the fear response of the “free” and lets the “guilty” decay in cells.

Alexander addresses how the police have been militarized in response to the tough-on-crime movement led by ambitious politicians . The way this book and Alexander’s amplified message raised public consciousness probably helped to contribute to a sea change—with all of the current administration’s continuance of imperialistic, hegemonic, and economically insatiable policies (drone strikes, energy policy, surveillance extension, American exceptionalism…) at least its members are rethinking sentencing policy and the war on drugs. But will this rethinking go far and be extensive enough? The Obama Administration did not equalize the crack-to-cocaine possession sentencing disparities, nor did it push for the legal system to respond to drugs as a health crisis. Alexander also presses her reader to understand that, although legislation may ease pressure off of the most impacted, it is not going to be the way we end injustice.

While this book focuses on the war on drugs and the racism inherent in mass incarceration, it isn’t a complete indictment of the prison system as one of subjugation of the classes, commodification of their bodies, destroyer of their communities, perpetuator of their oppression, and a method of forced migration that furthers gentrification. The Prison Industrial Complex, as it has metastasized, is a collision of pathologies of the American collective psyche that values profits over people and White bodies over all others. It is a state-sanctioned theft of property and personhood. And while Alexander uses statistics that are helpful to illustrate the quantified aspects of an issue, I worry that we will connect with the numbers and not the people impacted. And while the PIC doesn’t necessarily have to be racialized, it undeniably is. Within the American context, and the specific ways in which race has been codified and valuated here, until we fully address and deconstruct White Supremacy, everything we create and implement as a national unit will be polluted by racially discriminatory execution, no matter how benign the language around it seems.

Not all people find this book palatable or easy to swallow. While reading reviews of the book, I noticed a lot of the unfavorable ones where people wrote about her being biased and, thus, uncredible. They state that drugs are still illegal and people committing crime is the problem. They write about self-responsibility and that she is cherry picking facts. Tulane University’s student-run newspaper, the Hullabaloo, ran a review that characterized the book as “hyperbole,” full of ”skewed statistics,” and concluded that Alexander should “go back to English class.” In some of these reviews, there is some critical discourse around her omissions that, if included, may have painted a fuller picture, but most of them sound like anti-Black racism and White supremacy deniers—people who are unable to recognize themselves as barriers toward racial justice and collective liberation because of their agreement with the myths that either this system works or doesn’t disparately impact Black, Latino, indigenous, and other impoverished and marginalized communities of color.

One critique of Alexander’s book I do agree with is that she doesn’t mention the myriad Black radicals of the past and present who saw the prison apparatus for what it was and resisted it. She ignores that history of struggle to maintain a liberal tone, tiptoeing cautiously, trying to pull the liberal middle-class left further left without alienating them. As Joseph Osel pointed out in his article, it is a “whitewash and a black out” that makes invisible the work that has been done and is being done. The state suppression of these Black radicals, therefore, also cannot be brought up along with all the political prisoners that are still imprisoned because they dared challenge the American authority. But talking about these people is essential in telling and understanding this story, precisely because it is suppression of potential political radicals that is at the heart of the social control that mass incarnation affords the U.S. government—social control that quells dissent.

I have been a witness to her dismissal of people and their work. I was in attendance, along with many other community organizers and social-justice-minded folks, when she spoke at Dillard University last year. At one point in her talk, she stated that we needed to “start a mass movement.” I was with her when she said she wants to abolish the Prison Industrial Complex. But she lost me when she failed to mention the various people and organizations I work with who have been on the ground in New Orleans and around the country fighting the multi-headed hydra. I spoke with her after the event and relayed my feelings that she just dismissed people in that room and failed to connect the audience with the work or the movement, and that a “shout out would have been nice.” She replied that she wished she would have. So did I.

That incident made me start to think about the celebrity activist/scholar who hops around the country and/or world telling of their “discoveries” while achieving fame and status and it made me ask what their role really is in dismantling social systems of oppression. And who are they accountable to? These are questions that I still ask—having critical conversations, even with other people in the movement, about revered movement icons and elders can be difficult and impossible, depending on how much rockstar koolaid has been drank. It is something we need to be conscious of as people who want to end all social castes. Holding one person above another is one of the core values that allows for mass incarceration to exist.

While this book and Alexander don’t go far enough for me in exposing that the globally sanctioned structure of racial casting has always led to state-proliferated mechanisms of domination and control, and although I find it unfortunate that someone who may still be grasping with all of these far-reaching effects is one of the loudest voices on this issue, maybe now that more people are having this conversation because of her book, it will force them to recognize the deep societal and personal implications of mass incarceration.

This August, Alexander released, via Facebook, a statement in which she acknowledged her siloed presentations of the past and vowed to “connect the dots between poverty, racism, militarism and materialism. I’m getting out of my lane.” Let’s hope she does and includes the environment, patriarchy, and other interconnected elements, because someone in her position has a great responsibility to expand awareness of the truth and all of the multifaceted implications that mass incarceration reveals. Without a holistic understanding of our current situation, we will be doomed to repeat inherited oppressive patterns and will never fully heal or move on.

Gahiji Barrow does community activist work and lives in New Orleans, he works for Voice of The Ex-offender and is a member of the national Prison Industrial Complex abolition organization Critical Resistance. He also hosts a news radio program on WTUL New Orleans 91.5fm on Monday mornings from 8am-10am.