When you first see the photographic constructions artist Matt Vis calls “Meditation Patterns,” you will probably not think, Ah, this is art about pain. These are not illustrations of pain, like many paintings of Frida Kahlo, Edvard Munch, or the growing body of work by professionals and amateurs in the online gallery at the PAIN Exhibit, but pain is the place where Vis’s Meditation Patterns originated. I say “place,” because when pain grows to encompass a person, it can become like a place, an unmapped territory of suffering beyond the boundary of the person who is experiencing that suffering. Anguish may be a better word, because extreme physical pain also colonizes the mind. The originating accident or disease becomes beside the point. Time, and even one’s sense of self, can lose shape in the unrelenting siren of the nervous system. This is the space in which Matt Vis created his Meditation Patterns. The actual, physical space was the hospital.

When he was fourteen and living in Grand Rapids, Michigan, Vis took his mother’s car (sans permission) and got into an accident, breaking his pelvis and rupturing his spleen. These were serious injuries, but he recovered. When he was in college, Vis and a friend were wrestling in a dorm room and he broke his back, a compression fracture that left him, according to his doctor, “lucky not to be paralyzed.” He recovered again and continued to live an active life: a sponsored skateboarder as well as an artist who would use his body to build things and to participate in performative aspects of his art. Then, in 2015, while working in the film industry in the special effects department, Vis had another accident, a compression fracture to his vertebrae, “an uninteresting fall, ”he specified, “not a cool accident.” In the aftermath of that injury and subsequent surgery, hurting and confined to a wheelchair or hospital bed, Matt Vis started photographing anomalies in the architecture around him.

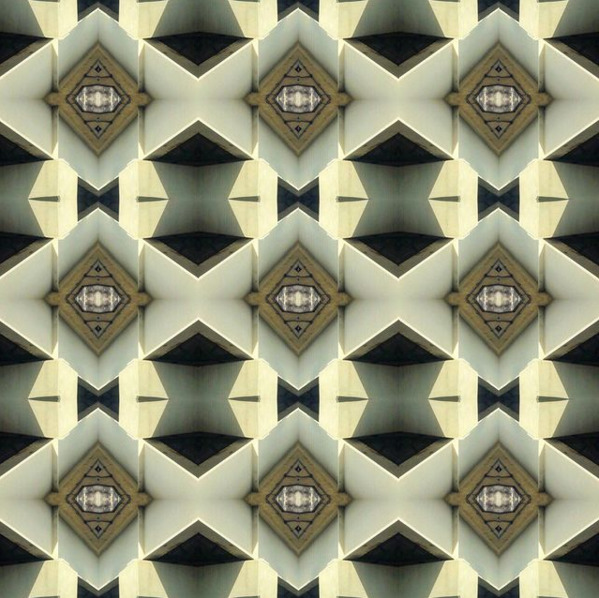

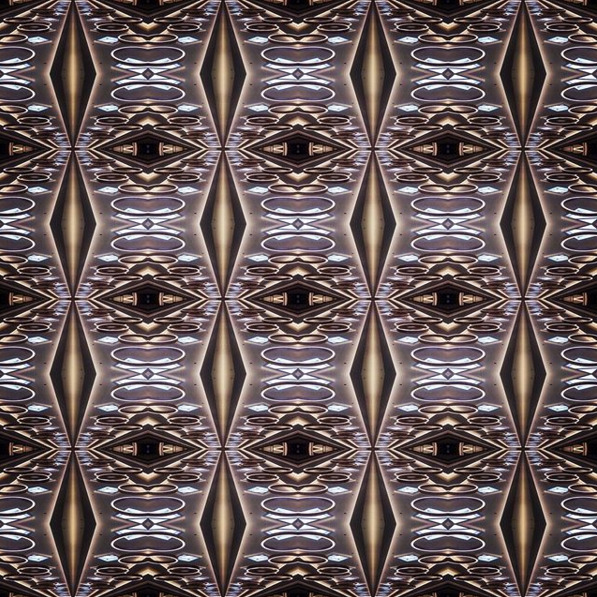

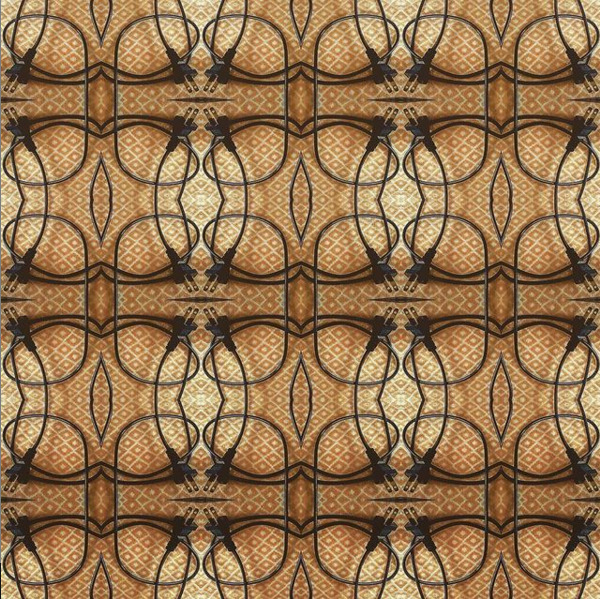

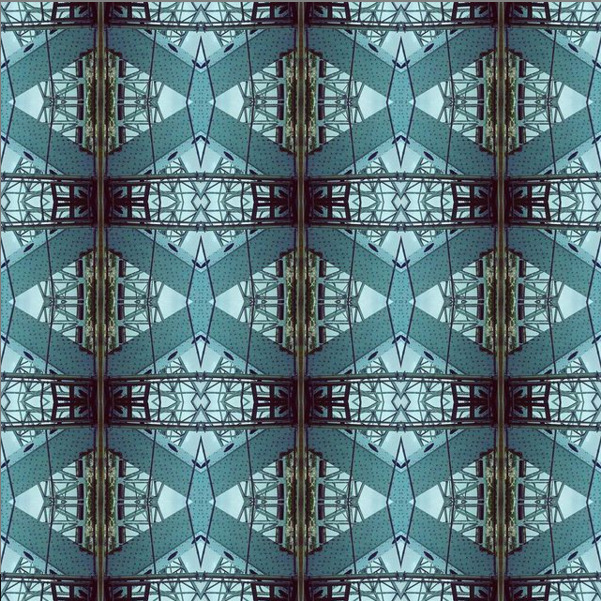

Each Mediation Pattern began with a photograph capturing “weird junctions” in the institutional space, architectural features lacking harmony Vis would come to call “situational anomalies.” He described these to me as abrupt changes in the flooring, a drinking fountain next to a garbage can, strange corners. He would photograph then reorder the image, seeking harmony through symmetry. Working on his phone, Vis created a mirror image of half the photograph, making symmetrical what had been askew, setting it like a bone. He continued cropping, making adjustments until the original image had become like a mandala, ordered, mesmerizing, and right, though, unlike a mandala, the form is based on the square of Instagram rather than the circle representing the universe. The artist continued coping with these bed-ridden or chair-ridden visual meditations after leaving the hospital, where the continuation of pain was more like a labyrinth than a direct road to recovery.

Matt Vis’s art career has been shaped by a commitment to work collaboratively with Tony Campbell under the name Generic Art Solutions (G.A.S). “We don’t have separate art careers,” he said. I asked him to compare working in collaboration and working alone making the Meditation Patterns. When working as G.A.S., an idea (his or Campbell’s) begins as a germ in one mind, grows as a dialogue between two minds, and is completed with a series of designated tasks. Bringing the concept to form, in other words, making art, is the goal. Pain is not a concept. Pain may be the opposite of a concept. It is certainly not collaborative, but a space one inhabits alone. Work created from pain necessarily goes in the opposite direction of collaboration, not outward but in. The goal was not art with his Meditation Patterns, Vis said, “The only goal was survival.”

When I asked Vis to describe how his brain feels on pain, he said, “It darts about.” He used the words “jumping” and “agitation.” A lot of art is made in a “flow state” or at least a state of focus that that ignores whatever lies beyond the canvas or clay. I asked if he thought that engagement in making other art would achieve the same state of non-pain as he achieves making the Meditation Patterns. Or, is there something particularly useful in working with pattern and repetition?

“I think there is something about rhythmic harmony… like tuning a radio, a guitar… an environment where I have a rhythmic harmony. The idea is to sustain it as long as I can. That’s where the relief comes in.”

These patterns are visually rhythmic but the process of making them is also physically rhythmic. The fingers, the cul-de-sacs of the nervous system, engage with repetitions of click, duplicate, flip, crop. A mindless task, one in which aesthetic decisions are not being made, may not have the same ameliorating effect.

Looking at the Meditation Patterns, you can, of course, see the patterns, but you can also perceive the harmony in a physical way, you can feel it in the body. Some works land as more cerebral and others more visceral. Some feel hopeful and some frightening. Because Vis makes the work on his phone and shares it on Instagram, when one looks at the Meditation Patterns on a screen, one sees the actual work and not photo-documentation of it as is usually the case when looking at art online. It is always back-lit and personal, in the original scale and medium. There is something essential about that. Sometimes the image of a painting makes me restless to go see the painting. These works say it is okay to stay in bed. (This work was printed and exhibited at Staple Goods in New Orleans last year, but I did not see the show and cannot speak to the experience of seeing them printed on paper and installed.)

I wondered what it would be like to be physically surrounded by back-lit, life-sized Meditation Patterns. Would it be like standing in a giant kaleidoscope? Would it move? Would it soothe pain? I pictured it something like entering Yayoi Kusama’s installation Fireflies on the Water, a private, mirrored room with water and string lights in the 2004 Whitney Biennial. Kusama also used pattern and repetition in her Infinity Net Paintings to cope with mental anguish. She called it “art-medicine.” Art therapy was a popular career path when I was in college. I was never really curious about it and after leaving college never heard much about it. I have enjoyed Kusama’s work but never really, really thought about her pain, other than noting it as part of a backstory included in an art catalogue or article. After speaking with Matt Vis about his work, about pain, I thought about Kusama more empathetically. And though I would not have denied as much, now I believe believe that art can be restorative in a practical, physical way.

In the course of a month I spoke with Matt Vis in person, on Zoom, and on the phone. Yesterday, I sent him a text message, almost as an afterthought as I was finishing this column: “Has pain taught you anything?” He replied with the iPhone double exclamation Tapback. Then,

“[Pain] has taken my mind to bizarre and frightening places. I still wake up in the middle of the night crying in pain…It can be scary and lonely and desperately confusing. Sometimes there is nothing else: just pain. No desire, no time, not even a sense of self. What comes to your mind after being nowhere and being nothing?…It’s something about harmony, but I can’t explain it.”

Don’t bother; it was a dumb question. Not every lesson can be articulated in words, which is the whole point of art. Anyway, the best answer is the work itself.

I took the title for this column from a book I read many years ago, C.S. Lewis’s The Problem of Pain. I remember little about it except that it was a theological explanation of why, in a world overseen by a benevolent God, people suffer. The phrase “the problem of pain” kept blinking in my head as Matt Vis and I spoke. If the problem is pain, does making the Meditation Patterns help solve it? No, the pain persists. Escape it? “Is ‘escape’ the right word?” I asked Vis. No, it’s not.

“If you’re in pain, you want to get away from it.” Vis says. “It turns out this work is not about that. It’s more vital, valuable, difficult to define. Escape is avoidance. This is trying to understand at a greater resolution.”

**All images not labeled are Meditation Patterns by Matt Vis (2019-2021)

Emily Farranto is a writer and artist. She started the art blog Village Disco in 2015 and her children’s book, Animals Mate, was published in July 2020.