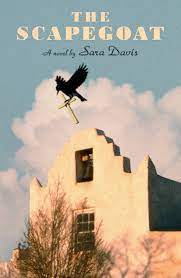

The Scapegoat by Sara Davis, FSG, 2021, $26.00, 210 pages

Murder mysteries often go by a formula. Somebody is killed, the protagonist goes on a search for their killer, stumbling upon multiple red herrings and tripping up on the clues. Eventually, the character’s brain can connect the dots, and the killer is revealed in a dramatic twist. The clues authors place within these narratives are often portrayed in two ways: excessively dramatized, with a shock factor to surprise readers. Or with a kind of subtlety that’s intended to go unnoticed, only to be revealed as essential pieces to the puzzle in the end. In her debut novel, The Scapegoat, Sara Davis chooses not to go with the usual formula for her murder mystery, resulting in a story that leaves readers as confused as the protagonist.

The book is written in first-person point of view, with the narrator detailing his father’s other life discoveries. Using the first person gives the reader a chance to empathize with this character and learn of his past with his detached father. Overall, Davis’s use of this point of view helps to further confuse the reader since the narrator continuously seems to be evading his own truths while delving into this mystery. Early on, I thought that this was just another typical mysterious male protagonist that you get in murder mysteries. The kind that appears to be all-knowing yet not wanting to be quick to reveal things at the very beginning for the sake of tension building. However, it becomes clear that this is the narrator’s way of avoiding his own truths, something Davis perfectly illustrates in every interaction that the narrator has with other people throughout the story. During a scene initially, the narrator even grows suspicious of the woman selling his fathers’ home because, in his mind, she asks too many questions. “What a busybody Sharon was, I thought. What a little investigator.” (10) In every criticism the narrator pushes onto other people, in every tiny detail that he seems to notice about their mindset, the interactions and internal dialogue reveal that the narrator is deflecting, second-guessing this mystery and the culprits to the point of blaming things on ghosts from the past, rather than himself.

“When I surfaced from my daydream the light in the room had taken on an unpleasant, congealed quality, and I was left with a pt of resentment. It was just like me, I thought bitterly, to dwell on the past–the past, the past, always the past.” (142)

This is not a story with a reliable narrator; Davis made the narrator an easily unlikeable character because of this unreliability. He comes off as pretentious, slightly misogynistic, and every conversation he has with another person is more like he’s sizing them up. Unlike other stories with unreliable narrators, Davis doesn’t create an account that inspires sympathy within the reader for the narrator. It’s hard to find any redeeming qualities about the narrator as he investigates his father’s death. The result is tension throughout the story between the reader and the narrator and the underlying dread of the reveal. Despite being a meticulous and detail-oriented person, the narrator becomes more erratic and unpredictable towards the end of this story. The mystery eventually becomes something that the reader will find themselves actively trying to solve more than the narrator since he slowly begins to lose control as the story progresses. This kind of loss of control is reflected in the story’s structure, as the orderly series of events becomes much more confusing towards the end. What started as a typical murder mystery ends more like a Twilight Zone episode, where time is really just relative.

To add to the unpredictability of her story, Davis also uses this confusing timeline to the story’s advantage. Dream sequences begin to blend into real life. The only things the readers can trust the narrator is being honest about are the murder mystery he’s currently reading and the people he gets involved with during his investigation (although even these are questionable sometimes.) The narrator finds himself questioning what could be honest and what couldn’t, further leaving it up to the reader to figure out. The dreams at first begin as small things, nearly pointless. However, the dreams start to reveal clues later on in the story, and it isn’t until the story has ended that the final truth is unveiled. You realize that some of the dreams, if not all of them, kind of gave the answer to the mystery at the very beginning. The narrator constantly seems to be looking over his shoulder like he’s under surveillance. What could be mere coincidences, such as instances of pamphlets being placed under his windshield or people even looking at him slightly wrong, only serve to prove his suspicions. He’s naturally distrusting, but he never seems sure of who. Davis uses these characteristics to distance us from the narrator as he begins to lose his grip on reality while still letting readers have the ability to understand the truth behind why the narrator is like this. When he’s finally faced with the reality of what he’s done, he seems so shocked that the mystery has slipped away that all his deflections and deductions have come back to him in this reveal. “Glass, I thought. Life, two fingers, and then the room went sideways, and because of the proximity of the shards to my open eye, I deduced that I was now lying on the floor.” (206)

The Scapegoat is perfect for readers who want a murder mystery that doesn’t follow the formula. For those who are well-versed in murder mysteries, this story is a refreshing take on an often predictable genre. This book is also an exciting and surreal introduction to the genre for those just getting into it. As the story progresses, time becomes hazy, and Davis crafts a mystery that leaves more questions than answers–in a good way. The closer readers might try to look, the more confusing the story gets. When combined with a complicated timeline, the result turns this mystery into a trick mirror that readers will find challenging to look away from and serves as an incredible debut.

Clarise Quintero was born in San Jose and is now living in New Orleans. She’s a current senior at Loyola University. Her hobbies include daily yoga practice, testing new coffees and tea for her caffeine fix, baking, and watching the Youtube series ‘UNHhhh.’ Her work has appeared in 433 Magazine.