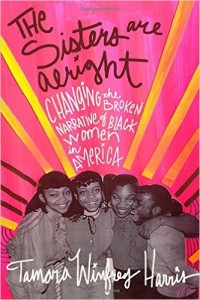

The Sisters Are Alright: Changing the Broken Narrative of Black Women in America, by Tamara Winfrey Harris. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc., 2015. $16, 147 pages.

In The Sisters Are Alright: Changing the Broken Narrative of Black Women in America, Tamara Winfrey Harris sets out to recalibrate the way we talk about African American women in the United States. Weaving together personal recollection, cultural analysis, and interviews with African American women from diverse backgrounds and with a wide array of life experiences, The Sisters Are Alright makes a compelling case that the white mania for diagnosing the supposed ills of the black family—a fixation shared by liberals and conservatives—misses the point and dehumanizes black women. While Winfrey Harris could develop some of her ideas in greater detail, and while she might rely a little less on examples from popular culture, The Sisters Are Alright nevertheless succeeds at impressing upon its reader the richness and diversity of black women’s experiences, challenging readers to rethink some of our most deeply held assumptions about identity. A vital, necessary book, it adds an important note to the conversation the United States is having about race and gender.

In her preface, Winfrey Harris lays out her rationale for writing the book:

My idea for a book was born out of the demeaning and tiresome nattering about the “black marriage crisis”—a panic that seemed to reach a peak a few years ago with endless magazine articles, TV specials, and books devoted to what black women might be doing wrong to so often remain unchosen. In researching that issue, I realized that the shaming directed at single black women is part of something much, much bigger—a broader belief in our inherent wrongness that we don’t deserve.

Winfrey Harris spends the rest of the book connecting the so-called “black marriage crisis” to the historical stereotypes that have been applied to African American women: from caricatures of slave women as either beasts of burden or lascivious jezebels, to caricatures of black mammies that existed before and after Emancipation, to modern stereotypes of the “angry black woman,” the “welfare queen,” or (again) the black jezebel. The critique demonstrates how black women have consistently been pathologized—and silenced—throughout American history. Of her interview subjects Winfrey Harris writes, “These women cannot represent all black women. But that is also the point. Black women’s lives are diverse. The diminishing mainstream portrait of black womanhood cannot contain its multitudes.” The book challenges its reader to rethink what might have shaped his or her understanding of what it means to be a black woman in America.

In one of the book’s most eloquent chapters, Winfrey Harris takes issue with the scrutiny Michelle Obama faced from white feminists when she avowed that her primary responsibility as First Lady would be to raise her children. In recasting Michelle Obama’s dedication to her family as a revolutionary act, Winfrey Harris underscores the point that context—history—means everything:

Except Michelle LaVaugn Robinson Obama, from the South Side of Chicago, ain’t Laura Bush. Or even Hillary Clinton. Michelle Obama is a black woman. And her ability to prioritize motherhood—much less be the symbol of motherhood for a nation—is revolutionary.

We live in a nation founded—in part—on the rape and degradation of black women, a nation whose economy was based on the practice of slavery, which entailed destroying black families, and a nation in which white wealth continues to be based in part on the segregation of black bodies. Americans should appreciate Michelle Obama’s decision to be “mom-in-chief” in this context, argues Winfrey Harris. Elsewhere in the book, she discusses the way Michelle Obama’s body has been scrutinized and notes the undue attention the press has paid to the First Lady’s biceps. All manner of cultural detritus—from The New York Times to Real Housewives of Atlanta—informs Winfrey Harris’s argument, and what’s distressing is how consistent cultural stereotypes remain across media outlets we might otherwise expect to differ, and throughout American history. What’s also distressing is how even seemingly positive stereotypes diminish black women: “Lisa Patton, fifty, says, ‘When people perceive you as the strong black woman, they don’t think of you as being a complete human being. They think that you don’t have vulnerabilities, that you don’t hurt, you just kind of soldier on.’”

One of Winfrey Harris’s real achievements lies in the way she defines the term revolutionary, a word we often associate with militancy, and therefore with men. Winfrey Harris’s passages on Nikki Minaj demonstrate how a woman can use a popular art form as an act of radical self-definition—which is, for a black woman, revolutionary. Likewise, Winfrey Harris writes compellingly about the ways in which Beyoncé has every right to label herself a feminist—and what the criticism she faced from white feminists for doing so means about those feminists. The first-person passages Winfrey Harris weaves throughout the book prove genuinely moving, demonstrating in tangible ways how stereotypes about race and gender work to dehumanize black women. In the context of the history—and the present—Winfrey Harris evokes, the simple act of a black woman asserting her humanity becomes a revolutionary act.

If anything, the book might benefit from more—more depth, more analysis. True, other writers have condemned the Moynihan Report. Nevertheless, Winfrey Harris’s argument might be more persuasive to those who aren’t inclined to share her view if she dedicated a little more time to spelling out exactly how those who blame single-parent households for social ills don’t just end up supporting racist policy, but using bad science to justify it. Winfrey Harris also does herself a disservice by relying overmuch on examples from popular culture. In one section, for instance, most of her examples of present day stereotypes come from reality television—in other words, from media we expect to pander.

Though critics from the left have derided Barack Obama for being too centrist, in part because of an invigorated electorate, the last eight years have seen a remarkable level of political activism: from Occupy to Black Lives Matter, the Obama presidency has radically altered the way we talk about race, as well as our understanding of how race intersects with class and gender. While candidates who might once have been relegated to the margins so far dominate the 2016 presidential field, even a self-styled radical like Bernie Sanders has come under fire for not making race more central to his platform. This book suggests that listening to what black women have to say might itself constitute a radical act.

Tom Andes has published fiction in Natural Bridge, The Blue Earth Review, Out of the Gutter, Best American Mystery Stories 2012, and elsewhere. He lives in New Orleans.