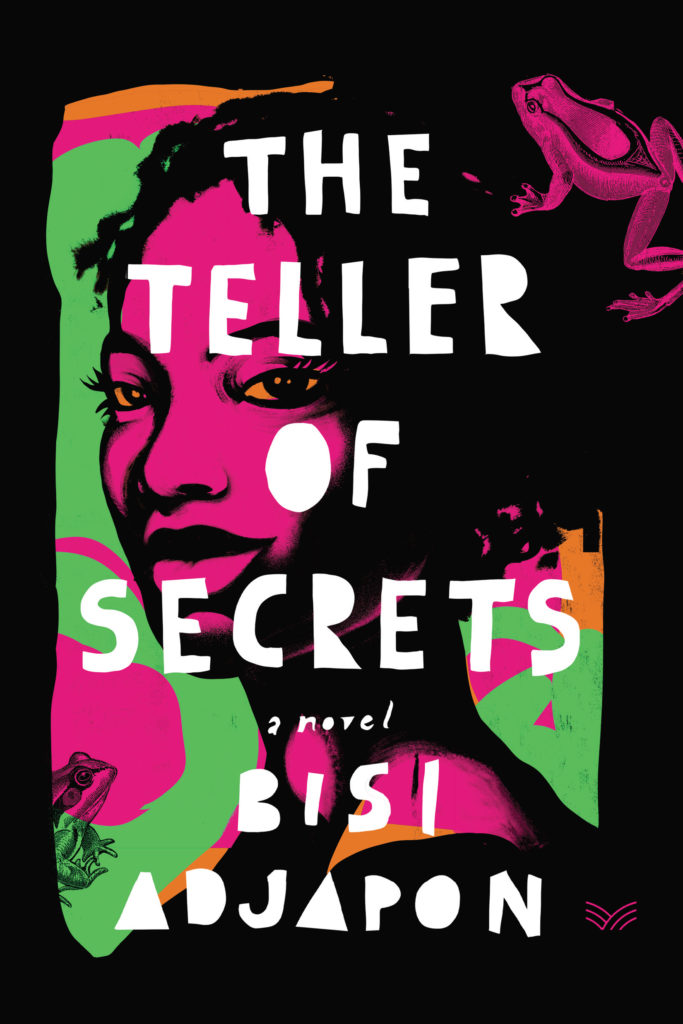

The Teller of Secrets by Bisi Adjapon. HarperVia, 2021. $26.99, 352 pages.

“Why do we women act as if men are so frail we need to hurt ourselves to make them look

strong? And look at how Auntie always gives the best meat to Papa and gives us the bones?

Then they get angry when Papa gives me more meat. Oh, I’m so tired of it all!”

Bisi Adjapon’s The Teller of Secrets is a coming-of-age narrative, spanning about 14 years of

Esi’s life as a young Nigerian-Ghanaian girl living in Ghana in the 1960s and ‘70s. Born in

Nigeria, Esi and her brother are separated from their Nigerian mother at a young age and

sent to Ghana to live with their father, their stepmother, and their older half-sisters.

Esi’s relationship to her Ghanaian family is full of contradictions and complexity. While she

worships her father for the kindness he shows her and his encouragement that she “can be

anything, even the first woman ambassador,” he also calls her a “good-for-nothing tramp”

for having attracted the sexual attention of a teenage boy when she is only eleven. And

although her stepmother and her sisters often treat Esi with love and care, they also keenly

police her behavior whenever they suspect her of exploring her sexuality and threaten her

that they will “whip you with a cane and teach you wisdom”. This results in a thoughtful

exploration of the impact of power structures on familial relationships and of the changes

that these relationships undergo as Esi grows older.

While Esi learns to hide her sexual exploration from her caregivers, this novel still is

unusually direct in its depiction of feminine sexual desire, making Esi far from the only

woman who voices her enjoyment of sexual relationships. It also portrays Esi “playing

romance” with other girls at her boarding schools, later discovering masturbation, and

ultimately both the pleasure and disappointment she finds in sexual relationships with men.

At the same time, the novel harshly depicts the trauma awaiting women in a society that

considers abstinence the only acceptable form of birth control when Esi ends up having to

suffer through an illegal abortion. During the only scene of the novel that is told through

detached third-person narration, Esi is only referred to as “the girl” and ends up screaming

when she sees the contents of her womb “ground up, like minced meat”.

Throughout the story, The Teller of Secrets expertly interweaves Esi’s daily life with the

impacts of Ghanaian politics, creating a vivid background for Esi’s youth to be set against.

Esi’s understanding of politics also clearly evolves, from calling the CIA and the KGB that

meddle in Ghanaian politics “alphabet people” to becoming ever more cynical, thinking that

it is “madness to do anything involving heads of state when said heads can be removed by

soldiers whenever they feel like it.” This also extends to an understanding of the impact

colonialization by the British and French has had on Ghana and its neighboring countries,

with Esi recounting that “if it weren’t for the French and British carving them up, the Ewes

would be one people, not French-speaking Ewes and Ghanaians speaking the same language

speckled with English.”

Language is, in fact, one of the things that makes the cultural setting of this novel so vibrant

and clearly resistant to the all-too-common outside view of different African countries as

one culturally and ethnically homogenous mass. The English text is regularly interspersed

with a few words or sentences in the characters’ native languages of Yoruba or Twi, such as

Esi mentally addressing her absent mother as “ìyá mi” or using culturally distinct greetings

literally translated into English.

Another thread contributing to the cultural fabric of the novel is the food that is constantly

cooked and eaten. While having to help her stepmother and her sisters in the kitchen at first

feels like a confinement to Esi, it eventually also becomes a refuge to her, and the

preparation of the food and Esi’s enjoyment of dishes such as fried plantain or okro takes on

a familiar rhythm for the reader. Food also is one of the primary ways in which many of Esi’s

female relatives – and, in the end, remarkably also her brother – take care of her, becoming

an expression of familial love.

The Teller of Secrets is not subtle in its criticism of the treatment of women; this is

communicated vividly through Esi’s internal monologue. Even at eleven, Esi wonders why

“women can be meanest to girls” after being punished by her stepmother and sisters. While

it sometimes seems unlikely for a young girl to have such acute insights into the gender

dynamics surrounding her based solely on her own observations, it is very effective in calling

attention to how women’s behavior is policed and measured by completely different

standards than the behavior of men. This novel also contrasts the harsh experience of

sexism with tender sentiments of female solidarity. When Esi witnesses market women

being assaulted, her thoughts about “those strong women, reduced to mush, their stores

reduced to ashes and dust” are full of love and care: “I want to wipe their faces. I want to

rub oil on their bodies and wrap them in silk.”

In the end, The Teller of Secrets is a novel that makes it easy for the reader to get lost in a

different place and time and Esi is a captivating character to follow. Although Esi’s thought

processes do not always feel completely age appropriate, remaining rather child-like for

parts of her adolescence, Adjapon’s writing gives Esi a strong voice and is beautifully

expressive throughout the novel. If the premise of a coming-of-age narrative about a girl

standing up to the patriarchal ideas espoused by her family and her society appeals to you,

then this is the book for you.

Karin Suter is an exchange student studying English Literature at Loyola University New Orleans. Her home base is Dortmund, Germany, where she pursues a degree in Applied Literary and Cultural Studies. She enjoys getting lost in fictional worlds with a steaming mug of tea next to her.