When I was young, each summer my family spent two weeks in a cabin at a rustic resort in the Adirondack Mountains. There was a sidewalk that led from our cabin by the lake to the dining hall that served three meals a day. This sidewalk was the only pavement in the camp. The texture was coarser and the color darker than the sidewalks at home. On two different rectangles there was a coin embedded in the concrete, pennies, heads up. The pennies had been embedded to mark the year the sidewalk was laid. One penny was older, more tarnished, and dated earlier than the other. In a place at end of a dirt road, where most of the camp was connected by wooded paths, this short stretch of smooth flat surface was an urban touch, a bit of outlying labor someone had taken pride in.

In our neighborhood where I spent the remaining fifty weeks of the year, the sidewalk was regular, except for a couple of spots; one was in front of our house, where the concrete was pushed up by the roots of a large maple tree. Our bike tires knew these anomalies well.

An object, a penny, embedded in concrete was a wonder. The fact that it was a piece of money was especially alluring. What would it take to remove the penny? I remember picking at it with my small fingernail. This month I saw two shows in New Orleans that recalled that sense of wonder, the mystery of an object embedded in something usually flat, uninterrupted and functional.

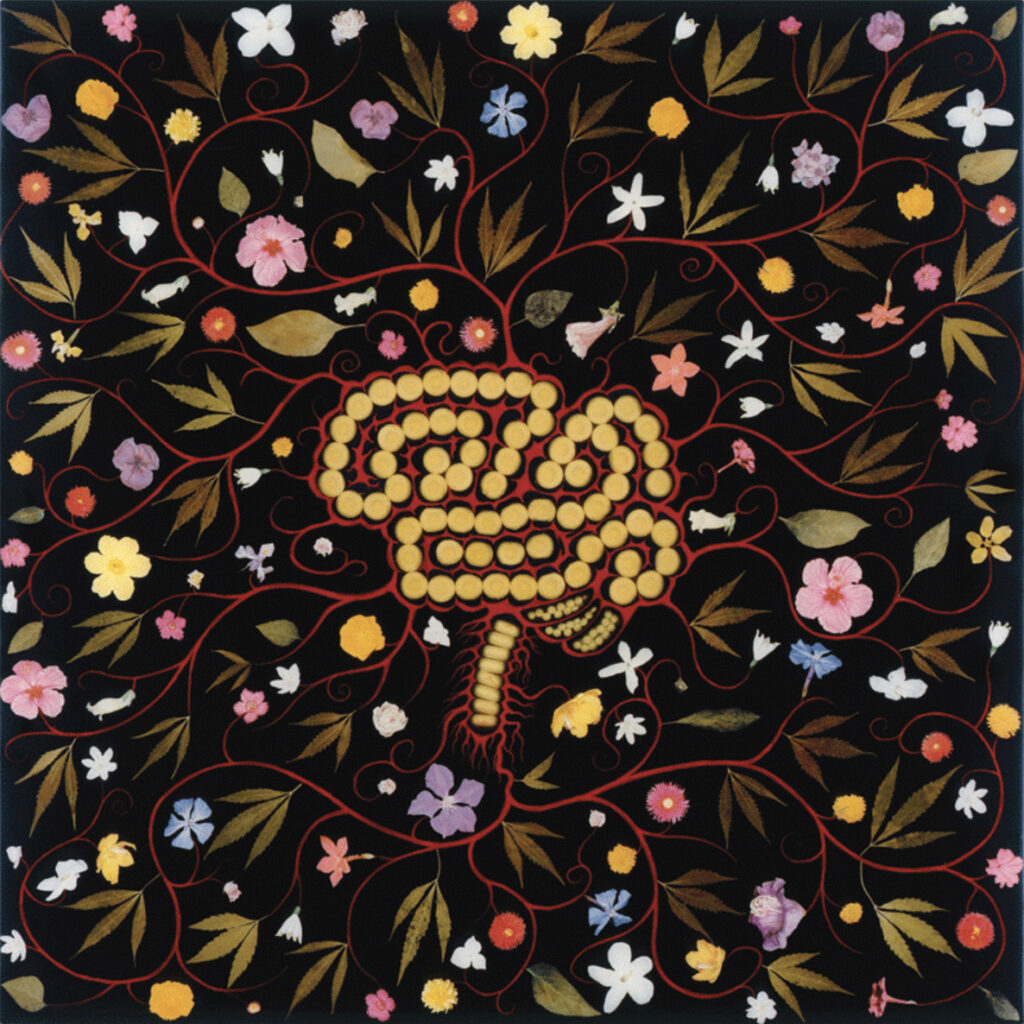

At Sibyl Gallery, a large space attached to a Riverbend home, Shabez Jamal’s solo show Close your eyes, and remember included concrete forms, small squares and rectangles holding partially embedded Polaroid photographs. The objects were arranged on unpainted plywood platforms. One side of the platform was covered with vinyl photographs of green leaves. The greenery and the concrete, the height of the display, placed the viewer at a vantage point less than adult sized, close to the metaphorical ground. A Polaroid photograph, an image as well as an object, is inseparable from its quality of uniqueness. These souvenirs had been permanently compromised by their encasement.

Across town, at Aquarium Gallery & Studios Jon Gott’s solo show Vestiges, offered visitors another encased object, a small snail shell embedded in the wall. Gott had raised the snail, which originated in the gallery’s prominently displayed aquarium.

In one exhibition there was an image-object encased in concrete, and in another, an organic object, interred in drywall. Both burials contained memory, the record of a life or lives. Prone to a combination of magical thinking and over-thinking, I dwelled on this situation for days. What does it mean to embed an object in a material? What does the surface–a wall, or a bit of concrete–come to mean? One piece represents memory and the other, a fractal, infinity. Or maybe they both represent both. They also reference time and life in the body.

At Sibyl, among the grid of concrete squares collectively titled In Remembrance of Us, a few works seemed bereft of a photograph, the surface of concrete uninterrupted. At Aquarium, one work titled Your Tender Heart in the Stars, appears to be nothing more than a small imperfect patch on the white drywall illuminated by a small industrial wall lamp. The heart of the piece was indicated in the list of works: “embedded glass shards.” What does it mean to break a small hole in the wall, pour glass in it and make a visible repair? What does a photograph you cannot see mean?

Artworks that involve acts of encasing, embedding, and burying are made of material, labor, as well as something intangible, a non-thing, a void. Poems rely on the strategy of loaded gaps, the whitespace of a page and of a pause. The meaning of a poem lies just as much in the gaps as in the words themselves. These works are material poetry.

After seeing these two shows, I walked through days, on paved surfaces, and past cemeteries. I thought about intangible embeddings and burials, what we avoid, what we remember. Anyway, it’s Easter and eclipse season, and another spring in another era of humans on earth burying and half-burying things, un-burying them later, for remembering, for forgetting, and for reasons I have not figured out yet.