About a week before I saw Dawn DeDeaux: The Space Between Worlds, at The New Orleans Museum of Art, Liza, who is fourteen years old, told me she had gone to a haunted house with her friends. A memory surfaced: a “haunted house” in Shoppingtown Mall, Upstate, New York in the late eighties or early nineties. My teenage friends and I walked through a dark labyrinth of temporary construction, huddled close to each other, exaggerating our fear for the fun of it. Sounds of howling, sounds of scary music grew and faded as we passed unseen speakers tucked behind gruesome still lifes, maybe an ax next to a severed hand. Costumed figures jumped out and we screamed, rushing out into the bright mall-light smiling, breathless, arguing about which of us had been the most scared. Liza’s anecdote, the time of year, or the general vibe out there of doom, hung over my visit NOMA.

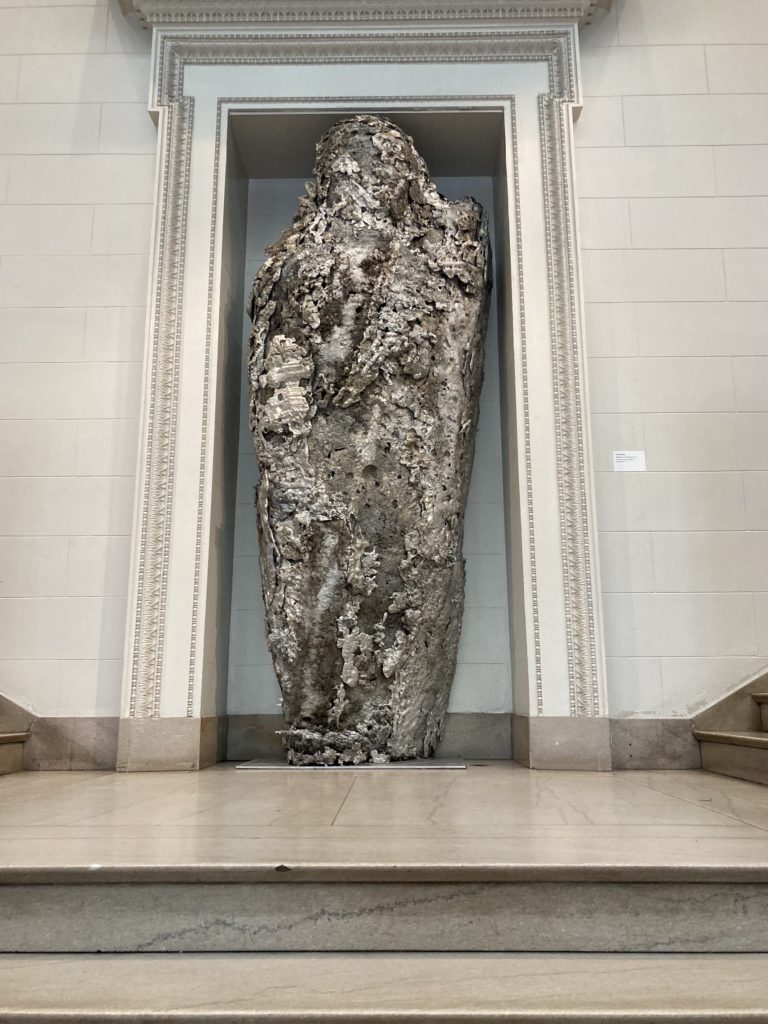

Dawn DeDeaux: The Space Between Worlds, a retrospective spanning the artist’s 50-year career, begins in the lobby where a lumpy ancient (or futuristic) looking sentinel looks down from the sculpture alcove on the stair landing. The bulk of DeDeaux’s work is situated in a dark cavernous space you enter from the bright corridor between the café and gift shop. You pass through a series of dark rooms, occasionally encountering a dead end). Light comes from video works and there are here and there, emissions of sounds or music. Near the entrance, human objects—tools, instruments, architectural furniture—imply that human is a past-tense word. A vitrine displaying bowls of soil might suggest that earth is also a past-tense word. Music plays from a creepy display of a drum containing banged up horns. I felt I was moving not through an art exhibition but a kind of haunted house.

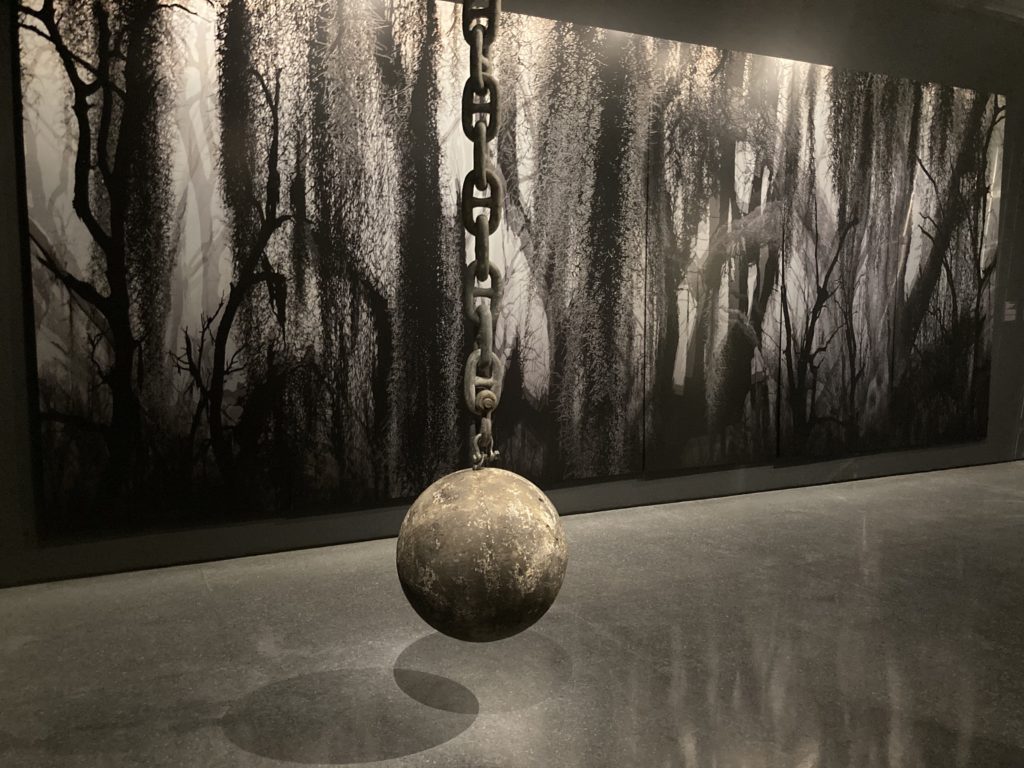

Out scaling everything else is a massive circular metallic structure appears as if it has busted through the walls or fallen from the sky. With a floor to ceiling digital drawing of a swamp behind it, the effect is like the opening of an episode of the X-Files. Next to the swampy crash site, in a separate small, dark alcove, fallen columns I imagine come from an Antebellum home in ruins, abandoned along with the silver objects displayed on a mantle after The Civil War, but civil war, past or future? Between people or was it a “natural” disaster, aided and abetted by humans? A wrecking ball swayed very slightly until I realized it was my own private hallucination.

Only one space in the show is fully lit and it contains three installations responding to Hurricane Katrina, the ensuing flood, and a devastating studio fire that followed the storm. These works are pretty and elegant in form–sparkling glass, narrow charred posts floating, and transparent slabs marking the depth of the floodwater in various locations in the city. This elegance is in stark contrast to the violence of wind, water and fire the work alludes to.

This gallery gives way to generous, dark space with large video projection and across the room, a small, glowing statue on a pedestal. Upon closer examination you see that the figure has lost most corporal features, retaining only the suggestion of human form. Next, a spot-lit bed is surrounded by 3-channel video of a sea turtle, a visitation of life in a show where you are surrounded by relics and ghosts.

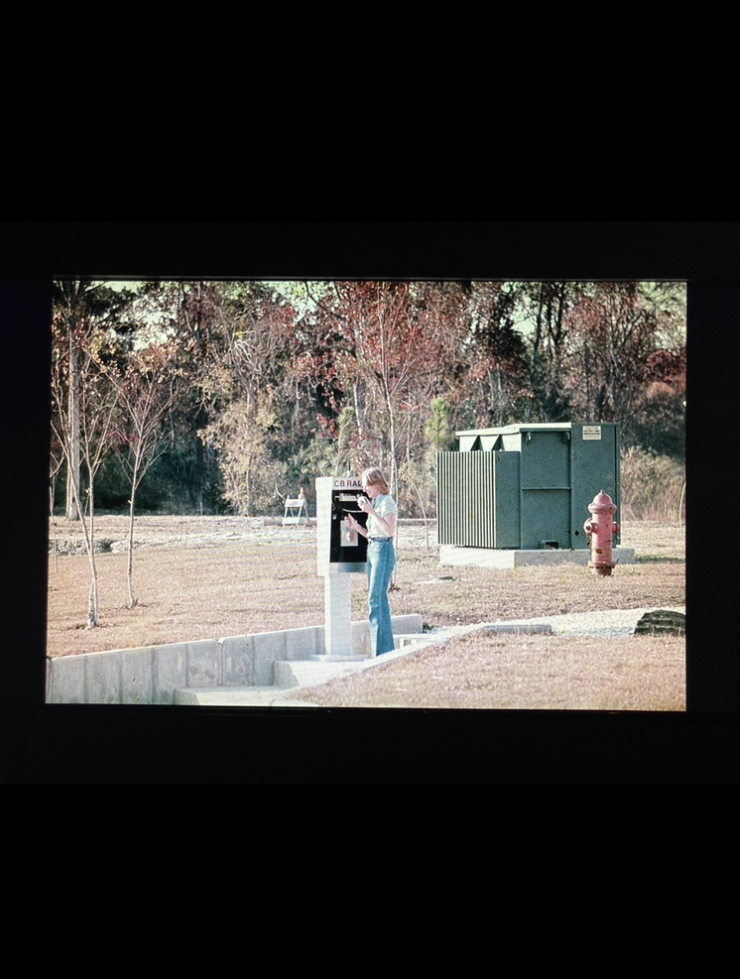

As you near the exit, the triggers shift from environmental to societal threats like war and mass incarceration. The exhibition concludes with a couple of older works about the human desire to connect with other people. In a vertically-formatted video a nude woman and a figure encased in plastic attempt tender contact but remain separated. The last artwork by the exit is a phone booth converted to hold a CB radio. This piece originally installed in multiple public locations in 1975-76 is documented in retro-tinted photographs of smiling nineteen-seventies people engaging with public art.

Living in a hurricane zone, a wetlands-at-risk zone, a rising-ocean zone, a mass-incarceration zone, a historically social-injustice zone, we see a lot of artwork that attempts to sound alarms. Dawn DeDeaux’s work about our troubled planet (inextricably linked to our troubled species) feels driven not by an agenda delivered from a pulpit, but by fear and grief deeply felt and articulated in art. My takeaway from Dawn DeDeaux’s exhibition is this: Dawn DeDeaux is scared and the artist has been addressing these fears (and subsequent grief) for many years. Her work comes from a place of vulnerability and concern for humans and for our planet, especially our swampy South. It also taps into the essentially optimistic activity of creation, of reaching out to communicate with other people, to say: what you feel, I feel. What I feel you feel. What happens to you happens to me.

Exiting the museum, it was a bright and beautiful day in City Park, though I could feel the residue of anxiety. When we tune in, we can probably all feel it. This is our world. This is our haunted house.