When African literature is published in the West, it is all too often realist, in English, and in the spirit of Chinua Achebe. But romance, science fiction, fantasy, epic, experimental poetry, satire, and political allegory all find expression in Africa, though not necessarily publication. Those who are called to write often have to hustle to get recognition by writing a coming-of-age colonial encounter tale or hustle even harder to have their unique voices heard. So the post-Achebe generation writer faces all sorts of firewalls. There is the publisher, often Western, who wants only one Achebe or Adichie, Ngugi or NoViolet at a time…one at a time. There is the African educational publisher whose mainstay, and therefore main worry, is getting the next examination book approved by the government. There is the Western literary critic who Africanizes a global novel so that it says something particularly “African” to the West (or at best flagellates the West). And there are the African literary critics ossifying African literature into the chambers of the anti-colonial literature of the 1950’s and 1960’s, all the while checking the anthropological street cred of the author. For all of them, the gods speak English and the African literary canon is its humble servant.

The hustle evokes a kaleidoscopic range of activities: the day-to-day creative writing grind; writing as a “side hustle” that rarely gives us material nourishment; the obfuscation of one’s own goals that is sometimes required to get African lit published in such a narrow publishing market; the trickery of the publishing industry in marketing themselves as open to African fiction. But the grind is also the innovative non-mainstream avenues for publishing being developed by the minute, the lightning speed at which life moves in most urban areas in Africa, the creative flows of languages and ideas across the continent, the unrepentant willingness to inflict the new on an unsuspecting public. The hustle is real. For this issue, we hoped to provoke some interesting and unpredictable writing and thinking that would reflect and respond to the spirit of the hustle.

Writers from all over the world responded to our call. Eighty percent of the submissions were from white non-African-identifying writers who thought they could hustle their way into a volume of African literature and had no qualms about it. But the others—so many of the others—were experimenting with forms and words and ideas that made us pause, and then shudder and then gasp.

The writers who are collected here have moved on from those stale modes that defined the supposed canon of African literature—they have left African literary criticism behind. They have no choice. They are writing from their own times and pleasures. Forget the history of slavery stable in its monstrosity, colonialism’s tug-of-war where both teams have uniforms, neocolonialism’s camouflaged teams wearing the opposing team’s uniform. (It may sound crazy, but there was a time not so long ago when it appeared that we still had class and national lines to be crossed.)

Now imagine the madness when emperors in their nakedness have done away with color, class, and national lines, yet all remain. Globalization today means sophisticated, cosmopolitan, globe-fracking corporate types ruling the world. And dictators with Facebook and Twitter accounts lording over us on their behalf. What kind of literature emerges from a people for whom the lines have been removed, for whom the field is suddenly 3-D and then some? It could seem that nothing has changed, yet everything has.

Enter the Sudan of today, into Abdelaziz Baraka Sakin’s “Fly,” where rebels from that or the other ethnicity debate the origin of the AK-47 over a game of cards while carving out crucifixes. Or, sweat out the extreme urgency of now in Bwesigye bwa Mwesigire’s “Susu,” only to learn that the system doesn’t hustle for you. Read the manual of care that our elders write to teach us how to sustain long-term intimate relationships in Yejide Kilanko’s “For the Love of Baba Bisi.” Let Stacy Hardy trap you in the belly of a cow, or let Makambo Tshionyi hold you captive in a predator’s private lair. Stephen Partington and Adefolami Ademola both take us to Syria, where they remind us of sweetness that precedes crisis and may yet remain. D.M. Aderibigbe cautions us never to speak to our mothers in the colonizer’s tongue, and A. Samwel’s “Malaika” is printed in both Kiswahili and English as a reminder that translation is where languages meet and converse with each other with no hierarchies. Bernard Matambo narrates the slideshow of his life, employing a genre recently developed in Japan for use by architects and designers, while Mukoma wa Ngugi mocks practically every genre familiar to African literary critics, including the detective fiction that he writes. And in the end, Unathi Slasha helps us undo all of our expectations for African literature and proposes a way forward.

There is one place where the Western and the African literary critic meet: at the table of the African realist novel in English. Look at their guest list. To find those who might not be on it, look at our table of contents. And look at what they are producing: deeply political aesthetic pieces; love stories sometimes without romance; zombie nightmares that will not be contained. There is no irreverence here—just a literature that has outgrown its literary critics.

But what is African literature? Is there, can there be, was there ever an African literature? In asking you have answered your question. African literature is a question. It is an open question that invites, and has to keep on inviting, different geographies, languages, and forms.

And so we offer you an invitation to enter this volume, stripped naked of your expectations and assumptions about what African literature is and can be. Let these writers shape a new topography.

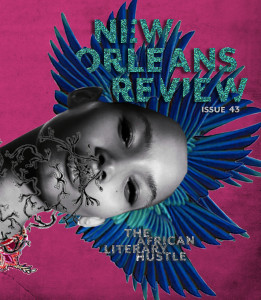

Purchase The African Literary Hustle Issue Here!

Mukoma Wa Ngugi is Assistant Professor of English at Cornell University and the author of the novels Mrs. Shaw (2015), Black Star Nairobi (2013), and Nairobi Heat (2011) and two books of poetry, Hurling Words at Consciousness (2006) and Logotherapy (2016). He is the co-founder of the Mabati-Cornell Kiswahili Prize for African Literature and co-director of the Global South Project-Cornell. The Rise of the African Novel: Politics of Language, Politics and Ownership is forthcoming (University of Michigan Press, 2018).

Laura T. Murphy is Associate Professor of English and the Director of the Modern Slavery Research Project at Loyola University New Orleans. She is author of Metaphor and the Slave Trade in African Literature (Ohio UP, 2012) and Survivors of Slavery: Modern-Day Slave Narratives (Columbia UP, 2014).