Katarina Janeckova Walshe

Flesh and Paint

It was dark outside my window in New Orleans and nearly dark outside Katarina Janeckova Walshe’s studio in Corpus Christi, Texas. We were finally on a video call; she was sitting in her studio, an enclosed space underneath her stilted house and I was in my home office. I apologized, remembering I was chewing gum, took it out and stuck it on my tape dispenser. Katarina held up a slice of pizza and said it was okay because she was eating her dinner. Speaking to her, one feels immediately on familiar terms. She signs emails and messages, “Hugs from Texas.”

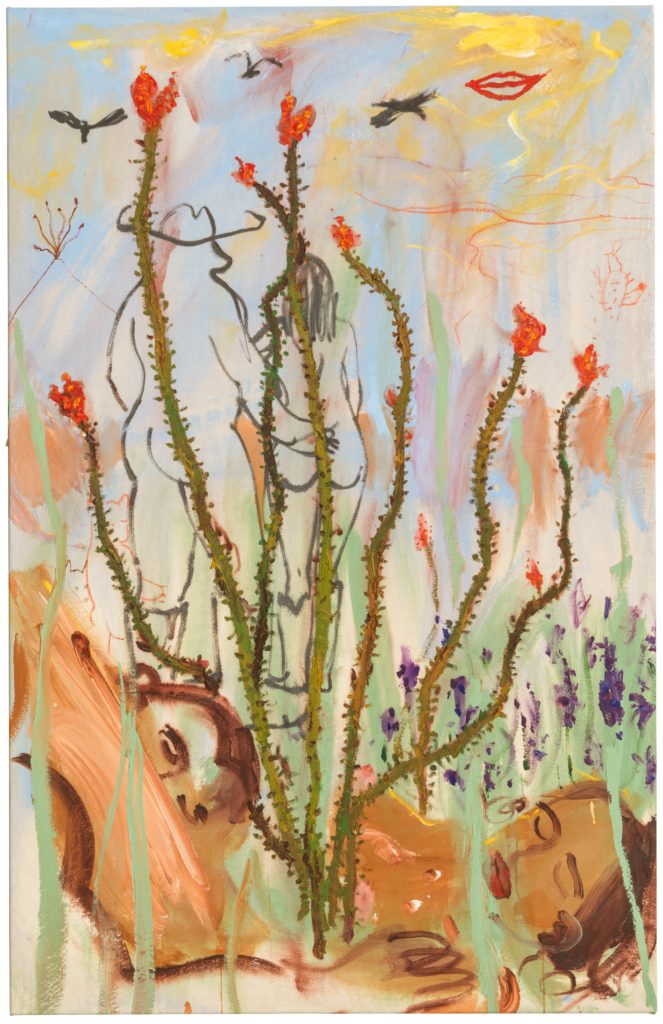

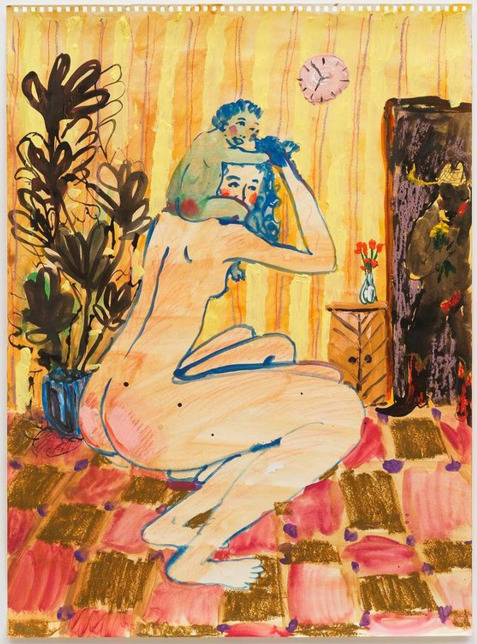

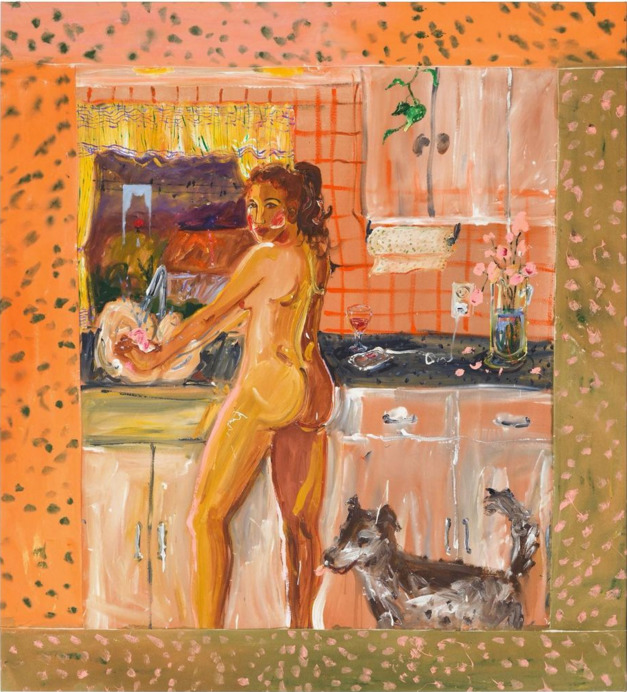

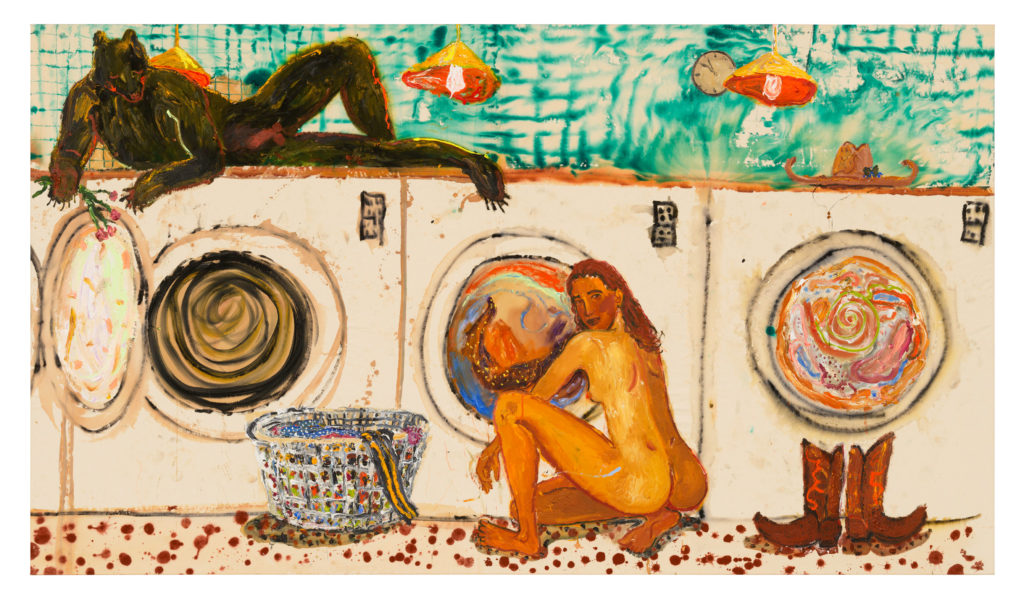

Katarina is from Slovakia and has lived in Texas, where her husband is from, for seven years. Domesticity with the backdrop of the Texas landscape is the preoccupation of Katarina’s recent paintings. In the time she has been in Texas, Katarina has become both a wife and a mother and as any wife-mother knows, this is a dual existence, the halves of which sometimes cohere and sometimes do not. In these paintings, the artist creates the fantasy of a unified space in which everything—all pieces of self, art, and domestic life—is in harmony. Her painted self, usually nude and often contorted in sex or housework, maintains a placid face, dreamy and pleased. Katarina paints her husband as a large, virile bear. This gives the paintings, many of which depict tender but explicit sex acts, a quality of humor and fantasy. The atmosphere within the paintings is both whimsical and quotidian, floating flora but also an iPhone charging on a kitchen counter and laundry that needs to be done.

Her paintings look fun to make; they are muscular and unrestricted, messy and attractive. The brushstrokes record the speed of a “flow state” or the rush driven by lurking obligations. There are also passages of detail and focus. She lets her child apply paint to the compositions, a pictorial record of what it means to have a toddler around and to embrace working with things as they are. Her exhibition at the gallery Dittrich & Schlechtriem in Berlin was titled Secrets of a Happy Home. The night it opened, she posted on Instagram that she was at home in Texas keeping her daughter Alenka company on her potty.

After talking a bit about motherhood, living in the American South and how I had found her work (Jerry Saltz’s Instagram), I asked, “Are you painting directly on the wall?” (as opposed to on stretched canvases).

Mostly I send work some place else so I don’t stretch them at the studio. A lot of times I cut the canvas crooked. The framers might complain because it’s a terrible job, but there is something also fun about painting this way, losing the excessive respect for new canvas and that feels good.

This frantic, spontaneous act of making the paintings is preserved within the work even once it is framed.

“What do you think is the biggest difference between seeing your work in person and seeing it in a reproduction?” I asked. She responded that on Instagram the work is, of course smaller, and you can identify the subject. Also,

When you are looking at [my painting] in life, you can see it’s almost abstract…When I paint, I almost paint with closed eyes…Shape doesn’t really have a border. [A face] doesn’t even look like a face when you look at it too long. You can see more spontaneity and clumps and imperfection different kinds of coincidences I like when I am painting.

“How do you feel when you are painting? What is painting like for you?” I asked. She paused, thanked me for the question, and said,

When I am painting, I know what I am doing. There are days when I have doubts whether I’m a good mum, partner, or second guessing certain decisions, but in the studio, I am always almost sure that this is supposed to be happening this exact way. There is nothing else like that.

Our Zoom conversation ended and a day or two later we arranged a live video walk through of Katarina’s show with Owen Reynolds Clements at Dittrich & Schlechtriem. He and I went virtually through the gallery and I only realized after that I never saw his face. But we were nonetheless seeing the show together. He was my surrogate viewer on the ground and we were, if such a term exists, co-viewing. I asked if he would show me the back of the large painting hung in the middle of the gallery like a curtain. I asked him to get closer to certain details. He volunteered to show me close-ups of his own favorite details. This felt slightly different that the video tour with the artist I described in Part 1. In this case I was seeing an exhibition with an emissary of the work. It felt very 2021. I appreciated what I may have previously taken for granted: seeing shows in person. But I was also excited by this new proposal of reaching out and (virtually) meeting a person for the first time in a new (virtual) space to look at art.

In Part One of this series, I wrote a list about how to look at art from afar. To recap:

- Look deliberately.

- Consider the physicality of yourself and the work.

- Remember that art is personal but offers perspective on universal conditions.

To appreciate the physicality of a work, it helps to have tactile knowledge of material and processes. For me, paint is the medium most closely connected to the body, substantial but unstable, moist and elemental, a thing that can be controlled to a degree but not entirely. It’s not just me; flesh and paint have long been associated with each other. Katarina’s paintings linger on particular conditions of the body: sexual arousal, fatigue, contentment. Her paintings are undeniably fleshy and undeniably painterly. The idea within a painting is inseparable from its substance. A painting is a record of the overlap of the painter’s thoughts their and physicality. Painting is the act of wrangling a goopy substance, trying to coax something into existence in the liminal space between control and relinquishing control, much like being a spouse, a parent, a person.

Look closer, zoom in to see the unevenness of the paint, a record of the artist’s gestures and attention. The story told in these paintings is not about a perfect life; no household is happy all the time. I see in these paintings a fantasy, part of the commitment of the protagonist––a painter, a parent and partner––to make art, to be happy, loving, satisfied, and to bend all experience toward gratitude.