Carmine Cartolano (Qarm Qart)

It’s Okay. No Worries. Never mind. Let it Go.

Carmine Cartolano, an Italian artist and writer, has been living in Cairo for twenty-one years. After a couple of email exchanges, Carmine and I met on a Zoom call in March. We talked about the pandemic and how it has affected our work, and life in our respective locations. At first, Carmine (who makes art under the name QarmQart) told me Cairo was following the example of Europe, mandating lockdowns then loosening restrictions last summer when the number of cases dropped. When cases started to rise again, Italy responded with another confinement, while protocol in Cairo was more ambiguous. At the time we spoke, the artist’s family in Italy was on lockdown. Below his balcony, the streets of Cairo were open for business.

“I don’t know where I am and what I can do. I am an Italian living in Cairo since twenty-one years. I always have this feeling of being between two countries…Now, this year it’s even physical, I feel physically in-between.”

Carmine spent the last year following the more strict protocol. He worked from home, made art digitally, and passed most of the pandemic alone.

“It’s a very strange moment. It gives a different twist to the production, to the creativity. Creativity has a main role in this moment because through it you go out of the space…you escape from reality through the things you do.”

Enough talk of the pandemic, we decided. Our conversation turned more broadly to art. Carmine describes his work as play, as a game full of layers.

“Superficially you see something, which is very simple and you may laugh about it because I use sarcasm and humor very much. But then if you go down, you can read things inside of it, and this is my practice. I like to read about reality and discuss problems around me.”

I had seen Carmine’s artworks on Instagram, many of which were digitally manipulated photographs that acted as proposals for an altered but possible world: buildings whose flowerboxes are bursting with blooms, immense graffiti murals of smiling movie stars. He described his last exhibition, which included a map of Cairo on the floor. Guests were physically, but also hypothetically, crossing the city as they crossed the room.

During his prolonged lockdown, in addition to working with digital images, Carmine made objects. These objects, not coincidentally, reference the domestic space. They are embroideries.

“I am a very practical person and I like to touch things. So this is where the embroidered works came from, the need to get out of his head and do something with his hands.”

I asked about his series of work that consists of objects embroidered with the word معلش (ma’lesh). The word ma’lesh in Arabic can be translated to, I’m sorry, it’s okay, no worries, never mind, and, you can put it aside. Explaining the origin of the work, Carmine said,

“Personally I am very tough with myself. When I waste time, when I don’t do something good, I’m very tough. One day I don’t know why, but I said to myself ma’lesh. Don’t be tough on yourself, ma’lesh. I thought of writing this ma’lesh everywhere because I had to remind myself.”

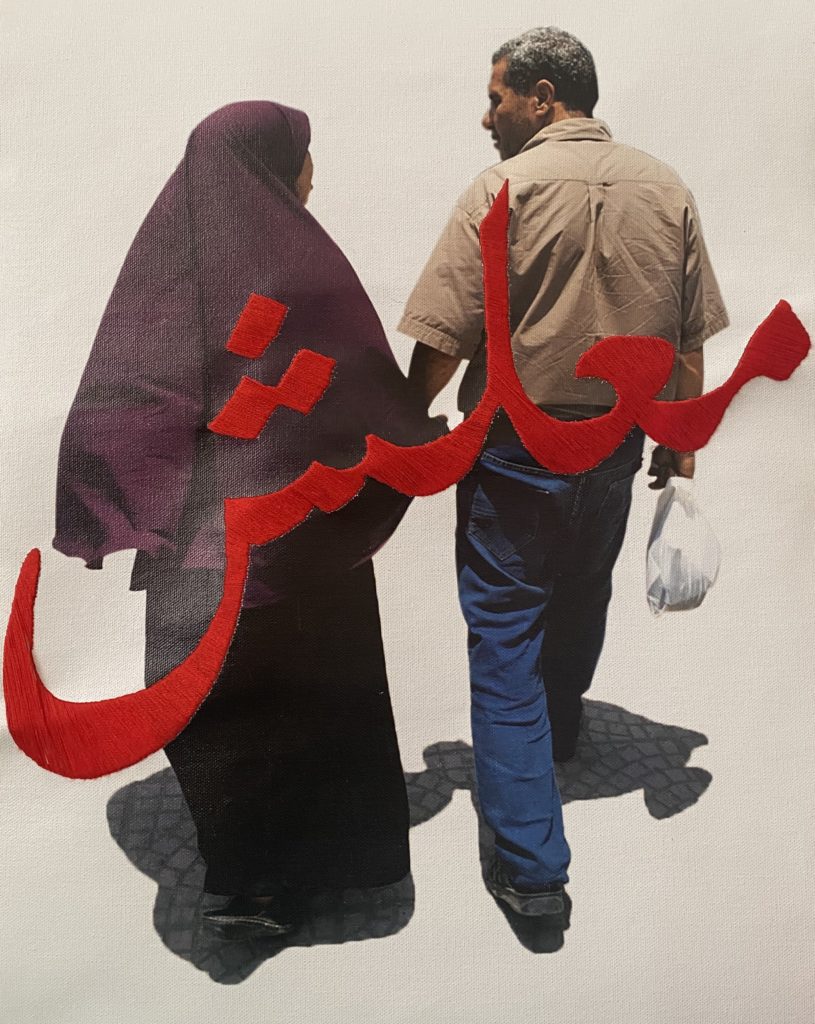

Carmine printed on canvas a photograph he had taken of a couple walking together in the street. The black and white image shows a man and woman from the back. He stitched ma’lesh onto the canvas. Before I knew what this word meant, I saw a couple and, unable to understand the text, I wondered, what are they saying? Are they happy? Are they being kind or unkind to each other? Once I knew the word, I saw tenderness between the man and woman. I saw them saying ma’lesh to each other. I saw the artist saying to them, ma’lesh.

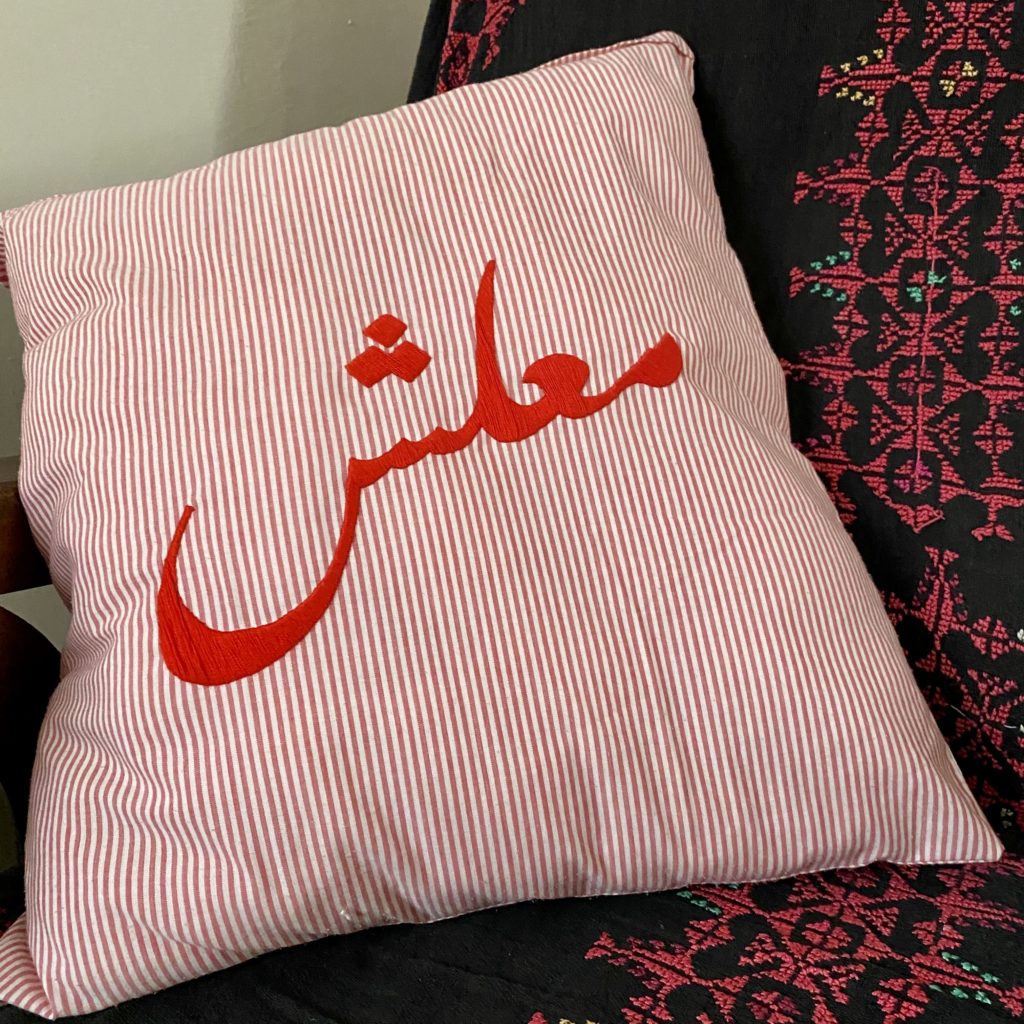

“There is also a pillow I can show you,” Carmine told me. He reached beyond the screen and retrieved a pillow that bore the words, ma’lesh. This is a sentiment on which to lay your head if ever I saw one. Ma’lesh. It’s okay. Never mind.

I asked about my favorite of the objects, a pair of jeans, on which Carmine had embroidered ma’lesh.

“The jeans [are] my jeans,” he explained, indicating that rather than being an object to display, they continued to be an article of clothing he wore. “Usually you have people you talk to, you have your friends and they mitigate your feelings, they help you to cope…but now it’s very lonely and being tough and being lonely is very hard.”

This column is the last of a three-part series about how to look at art from a distance. Looking at the work of three artists, Abdul Rahman Abdulla in Perth, Katarina Janeckova Walshe in Texas, and now Carmine Cartolano in Cairo, I am thinking not only of how to look at art from a distance, but why look at art from a distance.

I had an Art History professor, Rita Hammond. She told us about dropping in on Georgia O’Keefe at the artist’s ranch out West. Georgia O’Keefe tried to turn Rita and her friend away and Rita responded with something like, “then what the hell is this all about?” I took it to mean that art is about connection, about a deeper, more compassionate, more interesting life. Georgia O’Keefe relented and Rita and her friend spent an afternoon with the famous artist.

The pandemic and its lockdowns gave me an excuse to reach out to these three artists and to connect with them more profoundly than I may have, had I simply seen their works in a gallery. It became about connection. My conversation with Carmine felt honest, personal. Since Carmine told me about the time he told himself, ma’lesh, I have also thought, ma’lesh, when I am being tough on myself. The fact that a thought in the mind of a person across the planet can become an art object, a conversation, and then become a thought in my own mind, that is profound. That is what art can do from any distance. It can remain a part of how you think and see and how you live for the duration of your life.

This period of time has been marked by the cruelty of the pandemic, and at times, cruelty between and within people. We have all suffered in various ways and to various degrees. Even now that life seems to be grinding forward into the next normal, anxiety remains near or within us. Carmine Cartolano’s ma’lesh objects say, it’s okay. I’m sorry. My dear—

“When you find yourself really suffering, you don’t know why because everything is really perfect, you have no problems, you physically are okay, your family is okay, you have money you have a job. But then you feel you are not okay…You are suffering because you are tough on yourself. I said to myself, this ma’lesh…Embroidering ma’lesh takes a long time, it’s a process, it’s like holding this ma’lesh in front of you when you finish the last stitch, its like you have really said ma’lesh to yourself and you accept it.”