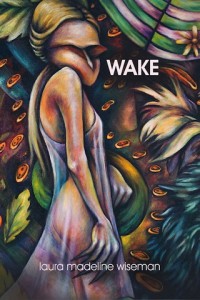

Wake, by Laura Madeline Wiseman. Aldrich Press, 2015. $14.00, 67 pages.

Unlike Emily Dickinson, who could not stop for death, Laura Madeline Wiseman embraces death and her cohorts—both mythological and real—in her newest poetry collection Wake. With carefully crafted images and a sly, exacting sense of humor, Wiseman contemplates what it means to be caught in death’s crosshairs. Whether pursuing death as a potential friend or being held down by death, Wiseman’s speakers accompany death, sometimes willingly, sometimes not. The speakers possess an adventurous spirit, both trusting in the journey yet questioning their surroundings and actions. As Wake opens, the speaker boards death’s cart, musing, “someone has to do this and I’m as good as any. I don’t know why I hesitate.” This choice begins a journey in which the underworld joins the everyday and the questions we keep hidden roam in daylight.

As the Lady of Death takes shape in Wake, she shifts from an elusive, shadowy figure to an active person, one who wants to become the speaker’s twin sister, offer kisses, and hold the speaker. There’s a push and pull; the speaker is at once attracted to Death and resistant to Death’s desire to consume her. In “La Petite Mort,” the speaker drives with Death as her passenger:

Death sings “Crazy Mary” and slides the cool white of her hand up the inside of my thigh. I hate to drive, so I can’t stop her. I’m wearing running shorts, so can’t stop her. I haven’t been touched by anyone and so can’t stop her.

In her exploration of the Lady of Death, Wiseman delves into the idea of death as pursuit. In many of the poems, death claims the speaker’s body with a sexualized, electric energy. It’s this unique figuration of death, combined with a speaker who seems to ride along very hands-in-her pockets, that pulls the collection along and allows Wiseman to dive beneath the surface, beneath our pre-conceived notions, to bring greater truths about mortality and desire to light. As this journey continues, Wiseman explores gendered violence through myth and fairytale and considers the ways that silence contributes to the perpetuation of violation. In poems such as “Considering Lore,” humor helps deconstruct the myths that both build and constrain us:

Ariel lied. She wasn’t mermaid or fish, just another voiceless woman with amnesia. Anyone would forget an event that turned every step into a feeling of knives.

Most powerfully, in “Anthology of the Dead,” Wiseman imagines her speaker putting up a flyer, calling murdered women forward to tell their stories. Hauntingly, they recall details, “she remembered the last time he was not quite scared, as he grunted, I’ve just strangled you.” One woman comes forward and “another woman held a bag her caste said didn’t exist.” Through the speaker, Wiseman considers how the silence about relationship violence continues even after death.

Just as Wiseman leads her readers to consider the darkness, she also leads her reader to consider the light and the role of love in the fight against violence and death. As the collection progresses, the focus shifts from death to monsters, such as the monsters from the children’s book Where the Wild Things Are or the monsters that hide under children’s beds. The monsters become stand-ins for the past, for a time in the speaker’s life when she rode with death. Ultimately, love conquers in Wake, and shuts the door on the scary things. In “Entrance to Death,” the speaker considers leaving her home to explore a mysterious opening in her house that leads to death. But, this time, someone holds her back from the journey: “you held my foot as I said, I’m going in. I’ve been there. I can come back.” When she decides to stay, the exit shuts.

In the end, the speaker’s journey from death to life, twisting and turning through myth, reaffirms life and love. What Wiseman does so masterfully in this collection is pull her reader through the darkest of territories then offer redemption. Love really does save the day in Wake—not the obsessive love of Death, who wants to possess the speaker, but the kind of love that checks on someone during a road trip and urges someone to leave that attic door shut for good. The gift that Wiseman so generously gives her reader is the ability to walk with the dead while knowing that love returns us to life.

Raylyn Clacher is the author of All of Her Leaves, forthcoming from dancing girl press, and a recent graduate of the University of Nebraska’s MFA in Writing program. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in South Dakota Review, burntdistrict, and Pamplemousse.