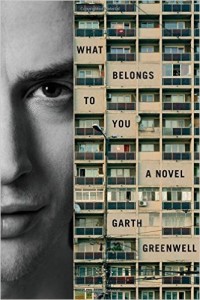

What Belongs to You, by Garth Greenwell. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016. $17, 208 pages.

Garth Greenwell’s novel What Belongs to You is a love story, but that doesn’t mean it ends with wedding bells. The romance begins in a public bathroom in Sofia, Bulgaria, when the unnamed narrator, a gay American man, meets Mitko, a local prostitute. Before they negotiate a price or agree on an act, Mitko “pulled the long tube of his cock free from his jeans and leaned over the bowl of the sink to wash it, skinning it back and wincing at water that only comes out cold.” As the narrator watches this ritual, his desire increases, and the specter of disease is acknowledged and symbolically washed away. Mitko is a tease, which works for the narrator, who prefers fantasy to action. In stunning prose that pivots from the vulgar to the cerebral, Greenwell’s debut explores the passion that originates in this subterranean cruising zone.

The narrator has never paid for sex before, “not out of any moral conviction but out of pride, a pride that had weakened in recent years, as I realized I was being shifted by the passage of time from one category of erotic object to another.” While the American has more money, Mitko seems to have more power in their constant negotiations between desire and denial. Mitko is an unpredictable force, one night threatening violence, another eating yogurt in the kitchen where he begs not to be left alone. On a wintery weekend trip to the seaside, the narrator spends the bleak, early morning hours on the beach, only to return home and find that Mitko has jacked off twice in his absence, can’t get hard again, and would now prefer to watch a violent movie. When Mitko is asked why he would expend himself alone, knowing the narrator wanted sex, they get into a fight, one of many, to determine if their relationship is defined by passion or cash. One of Greenwell’s strengths as a writer is in his ability to parse out the murkiness of attraction and the ambivalence of the narrator’s love. The American wants to be more than a client to Mitko, yet he also wants the perks of being a paying customer. He is sometimes overcome with desire, curiosity, and empathy for Mitko; other times he is disgusted, bored, or fed up.

The love between the narrator and Mitko is more operatic than mix-tape. The American is grasping for ecstasy, while Mitko’s motivations stem from the hungry reality of his poverty. This tension between the sexual sacred and the bodily profane serves as a plot, and the book moves forward through beautiful revelation and analysis of this dichotomy. When Mitko comes over, he uses the narrator’s laptop to Skype his other clients. Mitko turns the computer to the narrator, as if to remind him of his role, and the two clients, one reading poetry on the bed, and the other a screen-lit face glowing on the laptop screen, regard each other with scorn and jealousy. When the disgruntled narrator returns to reading his book, he laments, “I couldn’t find what I had found in it before, the recovery of something like nobility from the mawkishness of desire, the sense that stray meetings in dark rooms or the shadowy commerce of my own evening could burn with genuine luminosity, rubbing up against the realm of the ideal, ready at an instant to become metaphysics.” In the free-roaming reach of prose like this, Greenwell creates arias out of seemingly sordid conditions.

In his essay “How I Fell in Love with Cruising” published by Buzzfeed, Greenwell describes cruising zones—including a public park in Kentucky where he grew up, the video stores along 8th Ave in Manhattan, and the bathroom under the National Palace of Culture in Sofia—not as chambers of shameful secrets, but as offering “undomesticated joy.” Here, as Greenwell explains, intimacy is not measured by duration. A unique language, spoken in graffiti and codes, leads to bodily interaction, which leads to mutual recognition, compassion, and reverence. Sounds religious, right? Or, to Greenwell, sounds like art. “Cruising itself is a kind of poetry,” he exalts. The novel is Greenwell’s explanation as to why cruising zones and the unique love shared there will not disappear even though, as gay rights are secured, secrecy is no longer required. He describes his work as counter-heteronormative, against the assumption that with gay equality must come assimilation.

To take something that seems ephemeral or profane on the surface, like transactional sex in a bathroom, and show the richness of humanity within it is a radical political act. As the narrator in the novel notes, “it’s hard to look at things, or to look at them truly, and we can’t look at many at once, and it’s so easy to look away.” Reading this book, you can’t look away. You witness a spectrum of passion and emotion too intimately to judge it. But Greenwell’s political concerns, while noble and erudite, are not why I recommend the book. I didn’t need to follow politics or identify as an activist to value its literary power. What Belongs to You is a complex and beguiling novel for your bedside, not a slogan for your Twitter feed. I read it quickly, with ardor, wonder, and gratitude as a meditation on love.

McKay McFadden is writing a novel about three friends hitch-hiking across Central Asia. She received an MFA from the University of Mississippi, where she was a John & Renée Grisham Fellow.