In a post-Christmas torpor, a kind of sensory malaise, I found myself recalling that a year ago I was at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Now, lying on my living room floor in the doldrums of a pandemic winter, I was scrolling through Instagram looking at tiny images of art, feeling nothing. Then I saw the stingray.

The account @lookatthisfuckinstreet, based in New Orleans, pairs photographs of astonishingly broken streets and sidewalks with deadpan captions like “look at this fuckin duck pond. Iberville at North Saint Patrick.” On December 29, 2020, there was a photograph of a stingray on a sidewalk accompanied by the caption, “Look at this fuckin sidewalk stingray. Gentilly.” My initial WTF reaction to seeing the stingray on the sidewalk was followed by a more urgent question: what does this mean?

(Once, in college, I found a small, red plastic ampersand on the sidewalk on Farnham Street. I believed it meant something. I wanted it to mean something.)

This image of the stingray woke me from a stupor; it made me feel something complex, and, consistent with my habit of magical thinking, it seemed to mean something. I wanted to know where in Gentilly this photograph had been taken. I wanted to go see the lost creature. And I had other questions that had not yet formed. I DM’d @kevinbforbounce, who had originally posted the photograph. I waited for an answer.

(In the hours that followed, I encountered more stingrays: first, another photograph on Instagram, then a mention on the radio. Only the first could be attributed to internet algorithms. Are there also metaphysical algorithms in the universe that determine what we encounter?)

The next day my sons, ten and twelve-years-old, and I were passing time in City Park, and I told them I wanted to stop in NOMA to see if there were any stingrays in there. The museum was free to Louisiana residents that day, so a drop-in would cost us nothing but a few minutes. I asked at the admissions desk if they had any paintings containing stingrays. The attendant said he was not sure but didn’t think so. Another staff member who happened to be stopping by the desk offered a more confident no. “Well, let’s look anyway,” I told my boys. In the second gallery we entered, my son spotted a stingray in a painting titled Fish Heaped on the Beach, by Willem Ormea. He did a victory dance in the gallery, and I appreciated the brackish moment of art mixing with life.

As the title suggests, the stingray in this painting is half hidden in a heap. But in other paintings the stingray is a visual and psychological focal point. Though the body of a stingray looks nothing like a human body, these fish have on their underside a mouth that resembles a human face. (The eyes are actually on top of its head.) This “face” in a painting, looking at the viewer, like and unlike the viewer, is alien and out of place. It speaks to the feeling of being alien and out of place.

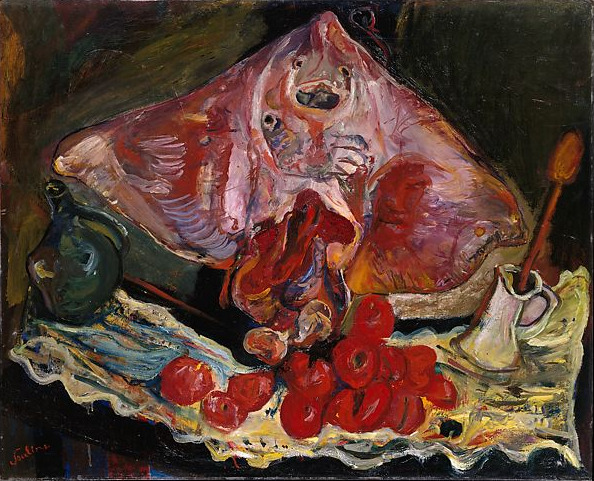

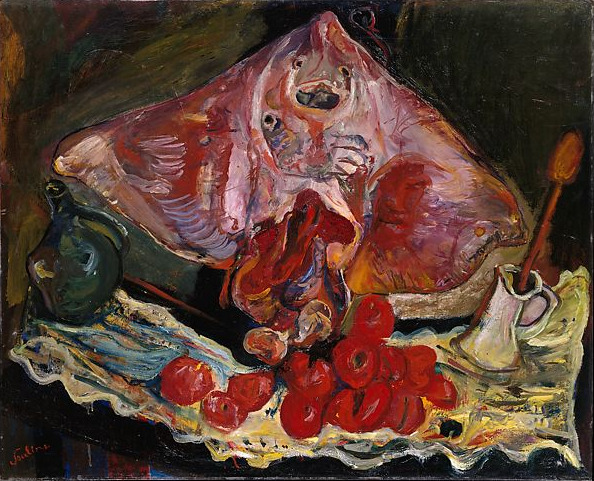

Chardin’s still-life painting may be the most well known stingray in art. The stingray that presides over the still life is gutted and dead while a cat, alive, arches its back, looking at something outside the frame. Soutine, apparently having seen the painting by Chardin at the Louvre, painted his own versions, the entrails bright red, its mouth open in a grin or grimace. One Soutine stingray is at the Cleveland Museum of Art and the other at the Met in New York. In William Merritt Chase’s painting, housed at PAFA in Pennsylvania, the stingray is not gutted and is wearing what seems to be a placid expression. In Enrique Martínez Celaya’s painting titled My Sebastian Holding a Skate, a boy holds a skate, a cousin of the stingray.

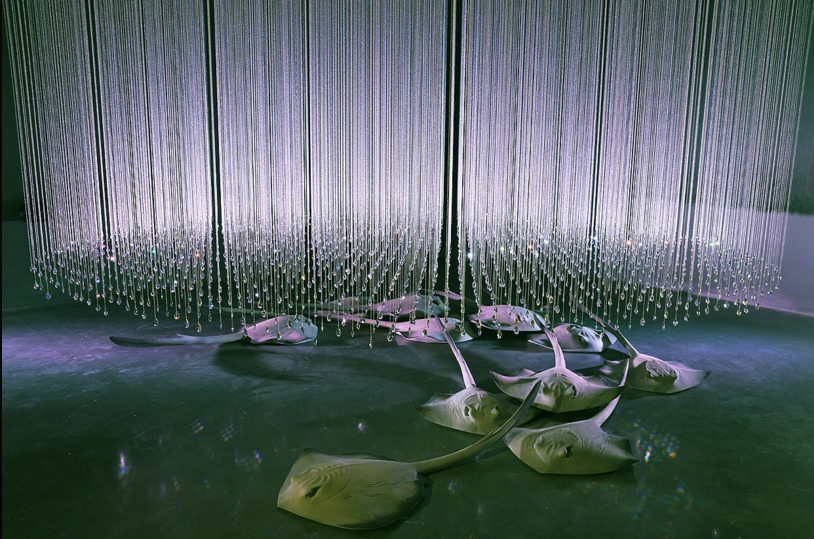

Abdul-Rahman Abdullah, who lives South of Boorloo/Perth, Australia, created an installation of a group (called a fever) of stingrays made of painted wood below ball chains hung with crystals representing the rain. This piece, titled Pretty Beach, contains the memory of his grandfather who committed suicide. After finding his work cross-referencing stingrays and art. I got in contact with him and we connected on Zoom. Abdulla said,

“Standing on the jetty watching the stingray, at the time you don’t think ‘Oh this is important …’ especially as a kid, you just kind of get lost in something and your world is full of those encounters. But I guess it’s not until many years later when something else connects to it or when something else refers back to that particular passage that it becomes––that it gains a meaning.”

In the memory recreated in Pretty Beach, the artist is an eight-year-old boy watching stingrays pass beneath the surface of the water. “The rain began to fall and they could no longer be seen,” Abdullah said, “The stingrays are there and then you can’t see them, but their lives have not changed…I wanted that to be a way of talking about somebody dying.” He added that stingrays feature prominently in Aboriginal art and later sent me links to examples.

(I thought, how strange that a stingray on the sidewalk in New Orleans led me to a farm in Australia. At the time we spoke, most of this piece had already been written including the note about finding the red plastic ampersand in college. At one point in our conversation, Abdullah made a gesture and I saw inside his forearm a bold tattoo of an ampersand.)

Meanwhile, Kevin @kevinbforbounce sent me a message explaining the stingray in Gentilly.

“[My friend] pulled over on New Orleans Ave or N. Broad (it’s the same street, but not sure when the name change occurs) to show me the stingray. He said it had been there for days, and that there was a 2nd one stacked on top of it that was now gone. Weird that only one got removed.”

And that was all I would learn about it.

I asked the internet what stingrays signify in a painting. It directed me instead to dreamstop.com, to what a stingray means in a dream.

“Stingray visits your dreams to let you know you are emotionally free of all bonds and ties. You have released all old emotional baggage and are ready to start anew…Everything is ready for you to start moving forward. There is nothing to fear.”

This was nice to hear, as a New Year was starting with a lot of 2020 baggage–personal, pandemic, political. The sad image of a dead stingray on an inland sidewalk is on my mind, but so is the transcendent image of Abdullah’s stingrays beneath the rain. Children engage in magical thinking and artists never really outgrow it. Magical thinking is like superstition, but instead of fear it’s propelled by a belief that behind everything is a benevolent logic that leans toward meaning. It was magical thinking that made me believe pursuing a lost stingray would take me somewhere & it did, & here we are, & what comes next?

Emily Farranto is a writer and artist. She started the art blog Village Disco in 2015 and her children’s book, Animals Mate, was published in July 2020.