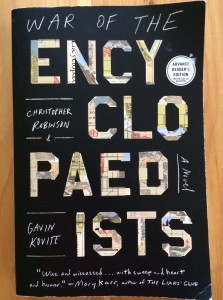

War of the Encyclopaedists, the first novel from writing duo Christopher Robinson and Gavin Kovite, is a coming-of-age roller coaster, an Iraq War novel, a millennial romance, and a buddy flick set to print. Robinson and Kovite toy with form, dance between perspectives, snark with the hipsters, and swap sex stories in the bunker. This is a book that, like some mixed up Congressional hearing, manages to go behind the scenes at both Planned Parenthood and Walter Reed. If that sounds like a lot, well, it’s because it is—Michiko Kakutani, writing in the New York Times, called the novel “telling portraits of a couple of millennials trying to grope their way toward adulthood”—but Robinson and Kovite, along with their literary alter egos, Halifax Corderoy and Mickey Montauk, keep the story moving.

When the characters are groping is at least as significant as where, because while the novel’s setting migrates from Seattle to Boston to Baghdad and back, it’s real home is late 2004, early 2005 America. Historians looking back on the United States at the turn of the century will no doubt focus on the 9-11 attacks and the March 2003 invasion of Iraq. But as it drags its protagonists through hipster art parties, post-graduate malaise, Internet porn, and student loan debt, the bitter disappointment of the Kerry campaign and the deepening quagmire in Iraq, War of the Encyclopaedists finds solid narrative ground in the upheaval immediately following America’s declarations of endless war. War of the Encyclopaedists is particularly adept in its exploration of how technology and a burgeoning Internet culture—texting, AOL chat, and Wiki feature prominently in both the form and content of the novel—shaped young Americans’ experience of this transitional moment.

Ultimately, though, this story belongs to the two young Americans, Hal and Mickey, whose perspectives the novel (mostly) follows. They’re smart, snarky, funny upper-middle class white kids with more cultural references than they know what to do with. And then they give themselves a Wiki. James Franco and Seth Rogen will play them just fine in the movie. The books starts and ends with Hal and Mickey throwing parties. Between those parties, they try some things—school, war, art, sex, love—and mostly flail. Mickey’s good intentions doom him and every Iraqi he touches. Hal’s content to have work (a cocaine medical study) instead of an STD or a child. War of the Encyclopaedists lets its protagonists down gently. Hal and Mickey, more aged than changed by their experiences, are affable guides to what was almost John Kerry’s America and they’re rewarded for their efforts with a lifelong friendship. That’s the kind of book War of the Encyclopaedists is, and the authors deliver the goods.

INTERVIEWER

War of the Encyclopaedists includes Wikis, MySpace chats, interview transcripts, scientific study journals, a pamphlet on abortion procedures, footnotes—I’m probably forgetting a few—and a third-person point of view that shifts between at least a half-dozen characters. The novel consciously defies easy characterization. How would you describe it?

KOVITE & ROBINSON

We stumbled into many of these extra-textual elements organically—they seemed right at the time and we liked them in the book, but we had to come up with conceptual backing for them, both to each other and to our editor. These characters walk through the world looking at text. And a book is a textual object. So it’s an easy leap to just include the text the characters read. It brings the reader closer to the characters’ perspectives, literally letting you see through their eyes, read what they read. Why describe the AOL chat log when you can just format the text like an AOL chat log? You can have a character look at a daunting platoon chart showing the 30+ people whose lives he’ll be responsible for, and try to describe what the chart looks like, or you can just put the platoon chart in the book and let the wealth of names overwhelm the reader directly. Novels are necessarily unreal in that they mediate experience through the artifice of language and the conventions of prose story-tellling. These are restrictions, fundamentally. They narrow experience to what is conveyable through text.

Joyce fought against this by using strange textual elements in Ulysses to attempt a higher degree of psychological realism. I’m thinking in particular of the newspaper office scene in Ulysses, where large font headlines permeate and interrupt the rest of the text, which is otherwise standard description and dialogue. The headlines serve to bring you closer to the character’s perspective, sitting in that office, seeing the news articles tacked up to the walls, those bits of language interrupting his thoughts as he tries to form his own language and receive the language coming out of the other characters’ mouths. I think at this point in the evolution of the English novel, though, this kind of technique isn’t distracting in the same way. People don’t bat an eye at an image in a book. For us, using these extra-textual elements is a way to broaden the scope of information we can convey and to approach a more organic, natural depiction of reality. It’s normal for us in our daily lives to process multiple sources of language at once. While chatting with our friend, we’ll pull out our smartphones and read a text message, maybe slowing our speech slightly, then go right back to conversing with our friend. It’s second nature. The forward and restrictive drive of traditional prose narratives don’t capture this well, they simplify reality in a way that it need not be simplified.

INTERVIEWER

There’s a more straightforward version of this novel that could belong solely to Montauk and Corderoy. You’re two friends writing a book about two characters loosely or not so loosely based on yourselves. And yet then we have Mani and Tricia, two female protagonists who carry the point of view for large sections of the novel. When and how did you decide to make the story more expansive?

ROBINSON & KOVITE

We stumbled into this, too. In the earliest drafts of the beginning, Mani was simply a plot motivator. But choosing to have a scene with Mani early on in the hospital, when she’s alone, not with Corderoy or Montauk, wondering about whether or not morphine will affect her potential pregnancy, we realized that she can and should have her own plot line. And when we started writing those scenes, they were fun to write! They were a challenge, and that was a good sign that we were heading in the right direction. We wanted to write a book that captured this post-graduate malaise we’d both experienced but also the optimism of growing up being told you can be anything–wanting to change the world and dwelling in cynicism. And through all of this, of course, these early twenties characters would be thinking about romance and sex. We couldn’t do all that with just two male perspectives. (Well, we could, but that’s a different book!) We needed the female perspectives to paint a complete picture.

Corderoy is more of a coward than Chris is in real life, less moral, masturbates more; Montauk is a little more unhinged than Gavin, prone to anger. So, it was us with a twist.

INTERVIEWER

How was writing Mani and Tricia’s sections different from writing Montauk and Corderoy?

ROBINSON & KOVITE

Corderoy and Montauk were easier to write for us. The process was sort of an act of translation of what we would do in the same situations. Corderoy is more of a coward than Chris is in real life, less moral, masturbates more; Montauk is a little more unhinged than Gavin, prone to anger. So, it was us with a twist. It was more fun for us to explore the emotional states of Mani and Tricia because it wasn’t just the act of plucking it out of our own heads. We had to build those characters from the ground up and then show them to friends and ask: Does this seem like a believable human to you? We had to read first hand accounts from female journalists when researching Tricia, I interviewed my female artists friends when writing for Mani. In that sense, it was also the passion or career (human rights activism or visual art) that was different from our own passions and experiences. Those differences, and not just the gender difference, made these characters harder to write, but much more satisfying to write in a way. Doing so strengthened our empathy muscles.

INTERVIEWER

Gavin, you’ve said Tricia is your favorite character. Why?

KOVITE

Tricia is smart and driven. She’s confident rather than arrogant. Arrogant people who are constantly trying to save the world are intolerable, right? I’m thinking about social justice warriors on the left or activist fundamentalists on the right. Tricia was a social justice warrior, originally, and kind of a heel or a foil that cast Corderoy in a relatively heroic light. As we edited, Tricia slowly became more warm, introspective, and developed some epistemological humility. This allowed her to learn and grow during the course of the story. Part of what makes me love Tricia is how far she’s come, not just as a character in the story but as a character in the writing process. Plus, she’s probably the smartest main character of the four.

INTERVIEWER

The novel mentions Nicolas Berg. His beheading was a touchstone for a lot of Iraq War watchers in its early years. Was that a moment that stood out for you from the early years of the war? Were there other moments that stood out as particularly emblematic of that time period?

There’s truth to that narrative, but it tends to dismiss or discount evidence of non-western militant groups actually being heinously savage.

KOVITE

Yes, that stands out. Another moment that stands out was the bombing of the UN mission, which didn’t make it into the book. We grew up in these schools where the narrative was that you were first told that people around the world are savages who don’t have the decency of civilized western people, and then told that in reality, we’re generally the savages, the West goes in and fucks shit up. There’s truth to that narrative, but it tends to dismiss or discount evidence of non-western militant groups actually being heinously savage. It’s very dangerous in certain parts of the Middle East, and many college-educated Americans have a hard time accepting this.

ROBINSON

Nick Berg seems important to me as a touchstone now, but he wasn’t for me at the time, in 2004. My world then was largely one in which the war was an abstract thing. Oil. The Bush Regime. Those people with the No More Blood for Oil bumper stickers. No one really focused on the horrifying specifics of what was happening. It was a lot easier to think about the war in terms of abstractions. Like the greed of oil companies. It’s easier to hate an oil company than it is to deal with the messy complexity of the situation. It’s easier to hate a bad system than to deal with the humans who are a part of that system and who may be trying to accomplish good things within it. This is why you get people blaming soldiers for their role in the Iraq War, which is crazy. Some soldiers fucked up, some surely enjoyed shooting people, but most were trying to make the best of a bad situation, and all of them gave up a large chunk of their agency to the American people who voted for politicians that sent them to Iraq.

INTERVIEWER

Early in the novel Mani goes through with a deployment marriage to Montauk, and later she completes a series of paintings depicting American soldiers and Iraqis in scenes “of extreme and sober violence in the cartoonish style of Dr. Seuss.” What’s the relationship between her art in the novel and your art as the novel?

KOVITE & ROBINSON

There’s an unreality to the world of the war from her perspective. So she has to approach it from this place of unreality. It’s fantastical. It only exists in her imagination. But it’s still horrifying. Which is why you have these blown up soldiers with this Starburst color palette. The absurdity and the deeply horrifying can coexist.

Killing each other isn’t absurd. It’s human history. We’ve been doing it for millennia. It’s horrifying but not inexplicable. The paintings straddle this line. She’s painting in an ironic style, but she’s genuinely trying to convey something. Seuss is aimed at kids, and part of her perspective in dealing with the war is kind of child-like, looking at a world without the tools to understand it. The information we were given about the war, the good and evil narrative, was fed to us like children, a very simplified version of something that is very complex. One of our goals in writing this novel was to reverse that, to show the simplified narratives to be false, to unpack some of that complexity by focusing on the individuals operating within those systems, be they the US Army or Boston University. Mani is doing more of a distillation. She’s collecting these conflicting emotional responses to the war and boiling them down to their essence. It’s a different project than our project, but our project is expansive, and so it includes Mani’s project within it. There’s an infinite series of Russian dolls in here somewhere.

INTERVIEWER

Did you want the war sections to convey some particular message or just be true to the experience of Montauk’s experience?

Killing each other isn’t absurd. It’s human history.

ROBINSON & KOVITE

We definitely wanted to explore Montauk’s individual experience. What was interesting for us was that Montauk began to realize, early on, how very out of his depth he was, and he recognized the danger of getting played as a useful idiot by the locals. And then he falls into that trap anyway, even though he’s on the lookout for it. It’s a lesson that is incredibly hard to learn any way other than the hard way, and Montauk, like so many other westerners in Iraq, learned it the hard way.

INTERVIEWER

Sounds like a decent microcosm of the experience of American soldiers in Iraq.

KOVITE

Well, it’s a microcosm of the experience of some American soldiers. Another reason why we wanted to explore Montauk’s experience rather than something large and diffuse called “the Iraq war” was that Soldiers’ experiences in that conflict were (and are) so incredibly varied. I often make the point that I don’t feel like I “fought” in a “war.” I didn’t fire my weapon once, and no one in my platoon did either, except for some warning shots at cars we thought were bombers (they weren’t) and maybe at some drive-by shooters making a getaway. We were more like cops in a really bad neighborhood (with mortar fire) than like infantrymen in close combat.

And yet Sadr City was a few blocks away, and the next battalion over was losing armored vehicles to enemy fire. Then there was the battle of Fallujah, that was quite intense, and of course the invasion itself, and then there were people up in Kurdistan that… well, actually I have no idea what those people were doing. Shooting hoops?

INTERVIEWER

Irony and detachment seem to be two of the themes this book is exploring. The characters in this novel often behave ironically. Are there aspects of the novel that you intended to be read ironically?

Irony is like cilantro. To some people it takes like soap, to others, guacamole is shit without it.

KOVITE & ROBINSON

I don’t think we were ever ironic about how we presented characters. We encourage readers to engage with them in a sincere way, though the characters themselves engage in irony. But that’s also the struggle of the characters: wanting to escape that irony, that dependence on cleverness for cleverness’ sake. They practice a kind of meta-earnestness. One of the central themes is the struggle to be sincere in a culture dominated by irony.

On the other hand, we don’t think people should escape totally from irony. If you’re too wrapped up in faith, if you don’t have skepticism, you end up a true believer, like a communist in the 30’s or a jihadi, or, at best, someone like Chris Kyle from American Sniper. (We’re glad he was on our side!) You have to have some of that detachment and cynicism.

One of the defining elements of these characters, and this generation, is that they’re skeptical of the broader narratives being fed to them from various news sources and authorities, but they also feel powerless to change anything. And the skepticism is a result not of some deep malignancy toward authority but simply from the plethora of contradictory information. Cynicism is one response to that, but it’s not sustainable. In life, it drains you, and in fiction, it bores the reader. Irony is like cilantro. To some people it takes like soap, to others, guacamole is shit without it. But, fundamentally, whether you love it or hate it, it’s an herb. It’s a flavor adjustment to the meat of sincerity.

Christopher Robinson is a Boston University and Hunter College MFA graduate, a MacDowell Colony fellow, and a Yale Younger Poets Prize finalist. His writing has appeared in many publications, including The Kenyon Review and McSweeney’s.

Gavin Kovite was an infantry platoon leader in Baghdad from 2004-2005. He attended NYU Law and is now an Army lawyer. His writing has appeared in literary magazines and in Fire and Forget, an anthology of war fiction.

Ryan Bubalo taught English and coached women’s basketball at the American University of Iraq-Sulaimani from 2008-2010. He’s written about Iraq war fiction for the Los Angeles Review of Books and is completing his first novel, Time of Our Choosing, about the war.