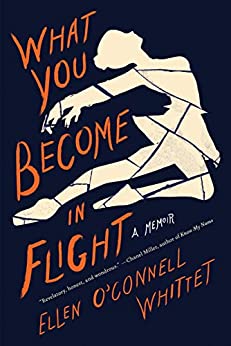

What You Become In Flight by Ellen O’Connell Whittet. Melville House, 2020. $17.99, 240 Pages.

At nineteen, Ellen O’Connell Whittet had a promising career as a ballerina ahead of her. The kind of ballet she was most suited to, she writes, was “rigid, constrained, correct, viciously classical—a piece that could have been danced in France or Russia in the 1850s.” But the inclination towards this exacting art form had been in her family for generations, beginning before she was born with her maternal grandmother, called Mita. While living as expatriates in the Philippines for her husband’s work in the Air Force, Mita enrolled her two daughters in ballet classes. It seemed like something “well-bred young girls did,” a means of cultivating grace and discipline. But there was another meaning to ballet as well: ballet as social currency. For Mita, who had grown up poor, “killing rattlesnakes in the dusty yard” of her family’s home in San Antonio, Texas, ballet was not just a type of dance, but a heuristic for good breeding and upward social mobility. While neither Whittet’s mother nor her aunt ever rose above an amateur level, tellingly, both of their daughters, the author and her cousin, would pursue ballet more seriously. “Ballet taught my grandmother how to be a woman, and she taught my mother and aunt those lessons in turn,” Whittet writes. “Their yearning would be my inheritance.”

In unsentimental, keenly observed prose, Whittet describes a childhood ardor for ballet that is deadly serious. She watched a “beat-up VHS tape” of Mikhail Baryshnikov and Gelsey Kirkland in The Nutcracker“nearly every day,” and referred to its male star as “Misha” because he “felt like a close friend.” Each Christmas she received ballet slippers as a gift, and because her father “had no inclination to dance” she began “praying out loud every night, for a younger brother to be [her] dance partner.” The French names for ballet steps (pas de chat, pas de bourrée, coupé) were a vocabulary she knew before she learned how to read words on a page.

She follows the typical path of a talented young ballerina—from children’s classes to more serious ones, pointe shoes, summers devoted to competitive training programs. While rehearsing a performance of Serenade, one of the classical ballets that she was born to dance, that Whittet suffers a serious injury to her spine that ultimately ends her career (and eventually leads her to writing this book). The moments that change the course of a life are notoriously difficult to write, but Whittet tells the story of her injury with clarity and a tautness in the prose that speaks to her mastery of the form.

This year, the docudrama Cheer, about the world of competitive, college-level cheerleading, was a megahit for Netflix. While reading What You Become in Flight, I could not help thinking of the parallels between ballet and cheer. Both are incredibly physically demanding, primarily performed by young women and girls, and both occupy an aspirational space in the cultural consciousness: a ballerina and a cheerleader are both ideals of femininity, the subject of adoration and emulation by little girls. From this jumping off point, the two forms diverge drastically: Cheerleaders are overstated where ballerinas are understated, loud where ballerinas are silent. There is a sexuality to cheer that is absent in ballet, particularly classical ballet. The athleticism of cheer is foregrounded; ballet is supposed to look effortless. To compare the two is in part to see the progression of societal expectations around gender, specifically, being female. In the wake of Cheer’s success, a mild backlash appeared, decrying the danger of the stunts the young cast performs, and their alarming rate of serious injury. While there is a “push-through-the pain” ethos in Cheer, by and large the physical wellbeing of the team is taken seriously (practice is attended by two athletic trainers), which is quite different to the culture of silence that Whittet describes in her book.

At sixteen she attends a summer intensive program where she immediately feels at home. She lives, eats and sleeps nothing but ballet, bound in camaraderie with her roommates, other teenaged dancers. “I could have been watching myself in a mirror, each gesture was so familiar.” But when she begins to experience serious back pain, a division between her and her peers begins to manifest. In fact, the issue is not that she has serious back pain but that she calls attention to and seeks treatment for it, which, she says, broke an “unspoken rule.” At the hospital, a doctor diagnoses an unstable sacroiliac joint, which effectively causes her pelvis to dislocate each time she dances. Still, Whittet is set on dancing through the pain, but instead is unceremoniously removed from her classes. Ballet, she argues, tolerates pain, even expects pain, but asks the dancer to “make it look effortless.” While demanding great feats of athleticism, it asks the body to ignore itself. “You need to listen to this pain,” says one doctor. But that is an instruction Whittet cannot follow, so anathema is it to the culture she grew up in.

Even while Whittet catalogues the emotional and physical damage that she inflicted on herself through ballet, her love for it, and her grief at losing it, are ever present, creating an engaging ambivalence in the narrative. Ballet was a demanding master, yes, but the highs of it clearly dazzle her still. In one harrowing passage we learn that after she fractured her foot at fifteen, Whittet, against her doctor’s advice, danced the role of Cupid in her school’s production. Each night before her performance, a nurse would inject her foot full of Novocaine so she could dance. But what she remembers most about the experience? How “on stage, the spot light draped across the stage like a hand.”

Part One of the book, devoted to Whittet’s ballet career, is more successful than Part Two, in which Whittet narrates her post-ballet life. The episodes dealing with the author’s family, the death of her grandmother, her mother’s breast cancer, and a first encounter with her future husband are particularly good, told with the light touch and precision that characterizes Whittet’s prose. Other episodes, like the one in which she discusses the 2014 Isla Vista killings at UC Santa Barbara, and another about her phobia of snakes, are interesting in their own right but do not fold into the larger book quite as well. The through line, an exploration of the body as a site of disappointment, healing, and ultimately strength, occasionally feels organic and is at other times somewhat forced. Part Two’s best moments lie with the family story at the heart of this book, a line about her mother wearing a low-cut dress at Whittet’s wedding stands out in particular, she is described as “perhaps for the last time aware of her breasts as merely ornamental or a nuisance.”

In ways large and small, What You Become In Flight asks how much is reasonable to sacrifice for the beauty of the form. Though her investigation is unflinching, Whittet does not offer a ready answer. Instead, it leads her to a second question: what happens when our bodies fail us? This second inquiry begins with Whittet’s own career-ending injury but is subsequently reframed through the lens of her family: her grandmother’s death, her mother’s cancer. In its treatment of these difficult themes, What You Become in Flight moves from the narrow scope of ballet to something larger. These are the questions that we are invited to ask, but not answer, in this deft and elegant memoir.

Sara Davis is from Palo Alto, California. Her debut novel, The Scapegoat, is forthcoming from FSG in 2021.