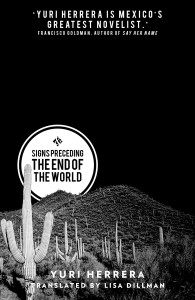

Yuri Herrera is a Mexican author, political scientist, and professor of Spanish and Portuguese at Tulane University in New Orleans. He has written several short novels, three of which have been translated into English by Lisa Dillman: Transmigration of Bodies (Las transmigración de los Cuerpos), Signs Preceding the End of the World (Señales que precederán al fin del mundo) and Kingdom Cons (Trabajos del Reino). His debut novel, Kingdom Cons, won the 2003 Premio Binacional de Novela/Border of Words.

NOR

What kind of things did you write about as a child?

YURI HERRERA

Mostly horror tales, I don’t know why. I remember one about a giant bird that would go around the city picking up people as if they were worms.

NOR

What made you want to study politics?

HERRERA

I didn’t want to study literature. I had this prejudice that if you wanted to do literature, that was incompatible with literary criticism. Now I know that is not always true: you will write if you want to write; it doesn’t matter what else you do in life. And I am glad I studied political science, which helped me to develop a critical gaze on power and how it reflects on the bodies of individuals.

NOR

Do you think studying politics gave you something to say?

HERRERA

Yes, I studied political science at UNAM [National Autonomous University of Mexico] when a lot of changes were happening in the world: the fall of the Berlin wall, fraud in the Mexican elections when for the first time in decades the PRI lost, the defeat of the Sandinista revolution after enduring almost a decade of terror sponsored by the Reagan administration. The political science department was a great place to discuss what was going on in the world. Beyond that, UNAM is one of the most fascinating universities. It is truly diverse, and the political debates never stop. My period there helped me to become conscious of the political implications of every word you choose to include in your text.

NOR

While your language is accessible, you have created a patois of your own, employing in your work invented or recontextualized words such as “jarchar,” translated into English as “to verse.”

HERRERA

I like to build the text with words that at first look like strange objects that seem out of place because in that way both the “strange” word and the environment where it is placed are transformed. In the case of “jarcha,” it is a medieval word that names the part of certain poems that were written in Arabic characters but was already resembling something like what would be the Spanish language; it was the “exit” of this kind of poem, so I used it as a sort of synonym for exit, exiting, underscoring that this kind of moving from one place to the other is not just a displacement but is a whole transformation, just like what happens to the characters in the book.

NOR

What was it like living in El Paso, Texas, when you were working on your master’s degree? To what extent were stories about border crossing and drug trafficking unavoidable subjects in a border town?

HERRERA

My time living on the Ciudad-Juárez-El Paso border was probably the most intellectually intense in my life. The border is a laboratory for new linguistic forms, political practices, identities. It is a place, or a sum of places, that is challenging all the time. And of course, the different kinds of violence that you see there (all interacting and feeding one another: the institutional violence, the organized crime violence) are part of “normal” life, even if you decide not to look directly at it.

NOR

You are known for deliberately abstaining from using certain words. What value is there to be found in silence?

HERRERA

Silence allows readers to make the text their own. Silences in texts are what make them ergonomical: it is how you bring into play the reader’s expectations and obsessions.

NOR

Can you provide an example from your work that illustrates how “silence allows readers to make the text their own”?

HERRERA

I try to not use words that are heavily codified; for instance, in Kingdom Cons you will not find the words “border” or “trafficking” because the way these words are used in the mainstream media turns them into simplifications. In the same way, I prefer not to use very often the actual names of places, so that the place happening in the mind of the reader is not limited by the preexisting clichés about such places.

NOR

Do you think it’s harder to retain silence in a culture that increasingly demands explicit answers and loudness?

HERRERA

Yes, silence has become hard to find, but precisely because of that it has become even more important in art. It avoids the superficiality of pre-packaged discourses and invites introspection. Silence is the opposite of selfies and short-lived breaking news.

NOR

What kind of research do you do before writing your books?

HERRERA

It depends on the project, but beyond the specific archival needs that a project might demand, what I always do is a sort of linguistic research, which means to reflect on the words I am planning to use or not use in the text, to consider their connotations. This kind of research is done not by reading dictionaries but by writing small drafts of scenes or images that will show you how these words work.

NOR

Can you explain what you mean by “I like to say that style isn’t surface; style is a form of knowledge.”

HERRERA

I mean that with every decision you make, you are stating something about the world, something that you know about emotions, sensations, time. It is not as if “reality” is something with certain words attached to it and the only job of the writer is to put them on paper. On the contrary, writing is about underscoring certain aspects of the world that appear to be new.

NOR

Signs Preceding the End of the World brings to mind recent discussions of Trump’s wall, though the book was published before his presidency. What, if anything, has changed for Mexicans living in the U.S. since the election?

HERRERA

Xenophobia has a long history in the United States, and Mexican workers have suffered many atrocities throughout the decades. What has changed recently is the way in which racists and xenophobes feel that their actions are legitimate. The insults uttered by Trump have made hate acceptable, and this has been taken as the cue to be intolerant or violent by agents of certain institutions and by vigilantes that justify terrorizing migrants by calling themselves patriots.

NOR

You portray the crossing of borders as somewhat otherworldly. Is this intentional?

HERRERA

I don’t know if that’s the word I would choose; what I can say is that for many people the crossing of a border and the starting of a new life after crossing it implies facing challenges that were inconceivable before.

NOR

How does it feel to return to Mexico now?

HERRERA

I go back very often, sometimes just for a few days, but that allows me to not lose touch with friends, colleagues, and with the particularities of our language. It is always a combination of joy and rage, joy for coming back home and rage for the unspeakable things that criminals (and not only the ones publicly acknowledged as such, but also the ones in the financial and political spheres) have done to the country.

NOR

And what are your thoughts on New Orleans?

HERRERA

It is a terrible place where extraordinary things happen on a daily basis. New Orleans is a portent of ideas and affection, so much more because it happens amid a constant tragedy that outsiders decide to simplify or not to see. I would love to write about the city one day, but even after several years here, I still feel I am just scratching the surface. I am willing to wait until I understand more before I try to do it.

Elizabeth Sulis Kim was born in Bath, England. She holds an MA (Hons) in Modern Languages from the University of Edinburgh and currently works as a freelance journalist. She has written for publications in the United Kingdom, South Korea, and the United States including The Guardian, Positive News, The Pool, HUCK, and The Millions. Her short stories have been selected for publication in Knight Errant Press’s 2018 anthology and The Tishman Review (both forthcoming). She currently lives between London and Buenos Aires.